- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Problem-Solving Strategies and Obstacles

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Sean is a fact-checker and researcher with experience in sociology, field research, and data analytics.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sean-Blackburn-1000-a8b2229366944421bc4b2f2ba26a1003.jpg)

JGI / Jamie Grill / Getty Images

- Application

- Improvement

From deciding what to eat for dinner to considering whether it's the right time to buy a house, problem-solving is a large part of our daily lives. Learn some of the problem-solving strategies that exist and how to use them in real life, along with ways to overcome obstacles that are making it harder to resolve the issues you face.

What Is Problem-Solving?

In cognitive psychology , the term 'problem-solving' refers to the mental process that people go through to discover, analyze, and solve problems.

A problem exists when there is a goal that we want to achieve but the process by which we will achieve it is not obvious to us. Put another way, there is something that we want to occur in our life, yet we are not immediately certain how to make it happen.

Maybe you want a better relationship with your spouse or another family member but you're not sure how to improve it. Or you want to start a business but are unsure what steps to take. Problem-solving helps you figure out how to achieve these desires.

The problem-solving process involves:

- Discovery of the problem

- Deciding to tackle the issue

- Seeking to understand the problem more fully

- Researching available options or solutions

- Taking action to resolve the issue

Before problem-solving can occur, it is important to first understand the exact nature of the problem itself. If your understanding of the issue is faulty, your attempts to resolve it will also be incorrect or flawed.

Problem-Solving Mental Processes

Several mental processes are at work during problem-solving. Among them are:

- Perceptually recognizing the problem

- Representing the problem in memory

- Considering relevant information that applies to the problem

- Identifying different aspects of the problem

- Labeling and describing the problem

Problem-Solving Strategies

There are many ways to go about solving a problem. Some of these strategies might be used on their own, or you may decide to employ multiple approaches when working to figure out and fix a problem.

An algorithm is a step-by-step procedure that, by following certain "rules" produces a solution. Algorithms are commonly used in mathematics to solve division or multiplication problems. But they can be used in other fields as well.

In psychology, algorithms can be used to help identify individuals with a greater risk of mental health issues. For instance, research suggests that certain algorithms might help us recognize children with an elevated risk of suicide or self-harm.

One benefit of algorithms is that they guarantee an accurate answer. However, they aren't always the best approach to problem-solving, in part because detecting patterns can be incredibly time-consuming.

There are also concerns when machine learning is involved—also known as artificial intelligence (AI)—such as whether they can accurately predict human behaviors.

Heuristics are shortcut strategies that people can use to solve a problem at hand. These "rule of thumb" approaches allow you to simplify complex problems, reducing the total number of possible solutions to a more manageable set.

If you find yourself sitting in a traffic jam, for example, you may quickly consider other routes, taking one to get moving once again. When shopping for a new car, you might think back to a prior experience when negotiating got you a lower price, then employ the same tactics.

While heuristics may be helpful when facing smaller issues, major decisions shouldn't necessarily be made using a shortcut approach. Heuristics also don't guarantee an effective solution, such as when trying to drive around a traffic jam only to find yourself on an equally crowded route.

Trial and Error

A trial-and-error approach to problem-solving involves trying a number of potential solutions to a particular issue, then ruling out those that do not work. If you're not sure whether to buy a shirt in blue or green, for instance, you may try on each before deciding which one to purchase.

This can be a good strategy to use if you have a limited number of solutions available. But if there are many different choices available, narrowing down the possible options using another problem-solving technique can be helpful before attempting trial and error.

In some cases, the solution to a problem can appear as a sudden insight. You are facing an issue in a relationship or your career when, out of nowhere, the solution appears in your mind and you know exactly what to do.

Insight can occur when the problem in front of you is similar to an issue that you've dealt with in the past. Although, you may not recognize what is occurring since the underlying mental processes that lead to insight often happen outside of conscious awareness .

Research indicates that insight is most likely to occur during times when you are alone—such as when going on a walk by yourself, when you're in the shower, or when lying in bed after waking up.

How to Apply Problem-Solving Strategies in Real Life

If you're facing a problem, you can implement one or more of these strategies to find a potential solution. Here's how to use them in real life:

- Create a flow chart . If you have time, you can take advantage of the algorithm approach to problem-solving by sitting down and making a flow chart of each potential solution, its consequences, and what happens next.

- Recall your past experiences . When a problem needs to be solved fairly quickly, heuristics may be a better approach. Think back to when you faced a similar issue, then use your knowledge and experience to choose the best option possible.

- Start trying potential solutions . If your options are limited, start trying them one by one to see which solution is best for achieving your desired goal. If a particular solution doesn't work, move on to the next.

- Take some time alone . Since insight is often achieved when you're alone, carve out time to be by yourself for a while. The answer to your problem may come to you, seemingly out of the blue, if you spend some time away from others.

Obstacles to Problem-Solving

Problem-solving is not a flawless process as there are a number of obstacles that can interfere with our ability to solve a problem quickly and efficiently. These obstacles include:

- Assumptions: When dealing with a problem, people can make assumptions about the constraints and obstacles that prevent certain solutions. Thus, they may not even try some potential options.

- Functional fixedness : This term refers to the tendency to view problems only in their customary manner. Functional fixedness prevents people from fully seeing all of the different options that might be available to find a solution.

- Irrelevant or misleading information: When trying to solve a problem, it's important to distinguish between information that is relevant to the issue and irrelevant data that can lead to faulty solutions. The more complex the problem, the easier it is to focus on misleading or irrelevant information.

- Mental set: A mental set is a tendency to only use solutions that have worked in the past rather than looking for alternative ideas. A mental set can work as a heuristic, making it a useful problem-solving tool. However, mental sets can also lead to inflexibility, making it more difficult to find effective solutions.

How to Improve Your Problem-Solving Skills

In the end, if your goal is to become a better problem-solver, it's helpful to remember that this is a process. Thus, if you want to improve your problem-solving skills, following these steps can help lead you to your solution:

- Recognize that a problem exists . If you are facing a problem, there are generally signs. For instance, if you have a mental illness , you may experience excessive fear or sadness, mood changes, and changes in sleeping or eating habits. Recognizing these signs can help you realize that an issue exists.

- Decide to solve the problem . Make a conscious decision to solve the issue at hand. Commit to yourself that you will go through the steps necessary to find a solution.

- Seek to fully understand the issue . Analyze the problem you face, looking at it from all sides. If your problem is relationship-related, for instance, ask yourself how the other person may be interpreting the issue. You might also consider how your actions might be contributing to the situation.

- Research potential options . Using the problem-solving strategies mentioned, research potential solutions. Make a list of options, then consider each one individually. What are some pros and cons of taking the available routes? What would you need to do to make them happen?

- Take action . Select the best solution possible and take action. Action is one of the steps required for change . So, go through the motions needed to resolve the issue.

- Try another option, if needed . If the solution you chose didn't work, don't give up. Either go through the problem-solving process again or simply try another option.

You can find a way to solve your problems as long as you keep working toward this goal—even if the best solution is simply to let go because no other good solution exists.

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

Dunbar K. Problem solving . A Companion to Cognitive Science . 2017. doi:10.1002/9781405164535.ch20

Stewart SL, Celebre A, Hirdes JP, Poss JW. Risk of suicide and self-harm in kids: The development of an algorithm to identify high-risk individuals within the children's mental health system . Child Psychiat Human Develop . 2020;51:913-924. doi:10.1007/s10578-020-00968-9

Rosenbusch H, Soldner F, Evans AM, Zeelenberg M. Supervised machine learning methods in psychology: A practical introduction with annotated R code . Soc Personal Psychol Compass . 2021;15(2):e12579. doi:10.1111/spc3.12579

Mishra S. Decision-making under risk: Integrating perspectives from biology, economics, and psychology . Personal Soc Psychol Rev . 2014;18(3):280-307. doi:10.1177/1088868314530517

Csikszentmihalyi M, Sawyer K. Creative insight: The social dimension of a solitary moment . In: The Systems Model of Creativity . 2015:73-98. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9085-7_7

Chrysikou EG, Motyka K, Nigro C, Yang SI, Thompson-Schill SL. Functional fixedness in creative thinking tasks depends on stimulus modality . Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts . 2016;10(4):425‐435. doi:10.1037/aca0000050

Huang F, Tang S, Hu Z. Unconditional perseveration of the short-term mental set in chunk decomposition . Front Psychol . 2018;9:2568. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02568

National Alliance on Mental Illness. Warning signs and symptoms .

Mayer RE. Thinking, problem solving, cognition, 2nd ed .

Schooler JW, Ohlsson S, Brooks K. Thoughts beyond words: When language overshadows insight. J Experiment Psychol: General . 1993;122:166-183. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.2.166

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

12 Apr What Affects Problem Solving

Many factors affect the problem solving process and hence it can become complicated and drawn out when they are unaccounted for. Acknowledging the factors that affect the process and taking them into account when forming a solution gives teams the best chance of solving the problem effectively. Below we have outlined the key factors affecting the problem solving process.

Understanding the problem

The most important factor in solving a problem is to first fully understand it. This includes understanding the bigger picture it sits within, the factors and stakeholders involved, the causes of the problem and any potential solutions. Effective solutions are unlikely to be discovered if the exact problem is not fully understood.

Personality types/Temperament

McCauley (1987) was one of the first authors to link personalities to problem solving skills. Attributes like patience, communication, team skills and cognitive skills can all affect an individual’s likelihood of solving a problem. Different individuals will take different approaches to solving problems and experience varying degrees of success. For this reason, as a manager, it is important to select team members for a project whose skills align with the problem at hand.

Skills/Competencies

Individual’s skills will also affect the problem solving process. For example, a straight-forward technical issue may appear very complicated to an individual from a non-technical background. Skill levels are most commonly determined by experience and training and for this reason it is important to expose newer team members to a wide variety of problems, as well as providing training.

Resources available

Although many individuals believe they have the capabilities to solve a certain problem, the resources available to them can often slow-down the process. These resources may be in the form of technology, human capital or finance. For example, a team may come up with a solution for an inefficient transport system by suggesting new vehicles are purchased. Despite the solution solving the problem entirely, it may not fit within the budget. This is why only realistic solutions should be pursued and resources should not be wasted on other projects.

External factors should also always be taken into account when solving a problem, as factors that may not seem to directly affect the problem can often play a part. Examples include competitor actions, fluctuations in the economy, government restrictions and environmental issues.

Carskadon, Thomas G, Nancy G McCarley, and Mary H McCaulley. (1987). Compendium of Research Involving the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator . Gainesville, Fl.: Center for Applications of Psychological Type, 1987. Print.

- Trending Categories

- Selected Reading

- UPSC IAS Exams Notes

- Developer's Best Practices

- Questions and Answers

- Effective Resume Writing

- HR Interview Questions

- Computer Glossary

Facilitating and Hindering Factors in Problem Solving

When a person is in an examination hall trying to solve a problem, and suddenly the teacher stands above that person, the student feels nervous and may solve the problem incorrectly. Common scenario? Another example could be when a person lives where the temperature is too high. Could this affect problem-solving? If certain factors could reduce the capacity to solve a problem, then can certain factors also heighten the skills to solve problems?

Problem Solving

Problem-solving refers to the cognitive processes involved in finding a solution to a problem. Nevertheless, it is well known that environmental factors affect our cognitive processes. Since problem solving also involves cognition, it is also affected by many factors. Not every solution needs to be effective. It may happen that the first solution that comes to mind is not the most effective, and the more the solution is brainstormed and discussed, the better solution one can come up with.

- Barriers to Problem Solving

The following factors obstruct problem-solving

Mental set − Mental set refers to our tendency to solve certain problems the same way we used to. These are fixed ways of solving a problem using old methods; there is no other way of thinking. For example, a student has three papers lined up and has to study for them all. The most common solution would be to study the first paper that is coming, but it may happen that this might not be effective. Another solution can be to study difficult, moderate, and then easy subjects or to study the easy ones first and then move on to the hard ones.

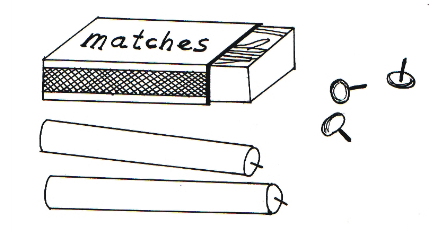

Functional fixedness − in this sense, it is the tendency to think of the most common use of any object. For example, everyone has seen puzzles like "Use this amount of matchsticks to make this or that object. However, most people cannot solve these puzzles, as they are fixed on the number or the most common use of the object. This involves abstract thinking to solve a problem, but functional fixedness could restrain problem-solving skills.

Irrelevant information − At all times, there are hundreds of stimuli around us in every form, be it audio, visual, or tactile, but we are exposed to various stimuli. Much information could be irrelevant to our problem-solving, creating dissatisfaction. For example, while someone is telling a riddle and we need to solve it, if one has observed much irrelevant information being given out and the answer is pretty obvious, but due to that irrelevant information, we pay attention to the information and thus miss out on the answer.

Insight − When we face unfamiliar situations, the old solutions do not help. The same perspective does not help in finding the solution to the problem. To get more insight into the problem, a different perspective is needed. However, as stated above, it is sometimes difficult for us to see things from a different perspective.

Resources available − Sometimes, even when we have found the solution, applying it to the problem is what matters. One thing to be noticed when we find a solution is its effectiveness. A person may not have all the needed resources, which can hinder solving a problem.

Facilitating Factors

Though many factors hinder problem-solving, on the other hand, there are facilitating factors as well:

Motivation − motivation is positively correlated with problem-solving skills. This means that the higher the motivation, the more efficient problem-solving is. For example, a person has to finish the presentation by a deadline, and this high motivation will encourage the person to look for solutions on how he can complete the presentation in the stipulated time. Motivation fuels the person internally and encourages him or her to achieve the goal more efficiently.

Self-efficacy − self-efficacy refers to the belief in one's capabilities. When a person is self-efficient, then the person knows that he will find the solution. This self-belief pushes the person to brainstorm and think about various strategies they could adopt to solve the problem.

Perception − Perception is highly correlated with problem-solving abilities. This indicates that we can find a solution when we see a problem as something that could be solved or a challenge. Nevertheless, on the other hand, if the person sees the problem as a threat or harm, the approach to that problem would be very different.

Teamwork skills − Most solutions are found when they are discussed and debated. When a person works in a team, s/he is exposed to a +variety of ideas and attitudes. This helps in finding an effective solution or modifying a solution that would be adaptive.

Measures to bring about Improvements in Problem Solving Skills

The following are the measures that are implemented to improve problem-solving abilities

Acquire Technical Knowledge in Your Field − It is well acknowledged that in order to carry out one's jobs and activities, people rely heavily on technology. Individuals must be knowledgeable about how to use technology.

Look for chances to solve problems − There are several chances accessible for delivering answers to challenges. However, these possibilities must be pursued. Individuals must raise awareness and expand their grasp of the opportunities. In certain circumstances, managers and teachers raise individuals' awareness of available options; in other circumstances, they produce their information.

Implement Practice and Role Play Techniques − Practice and role play techniques are thought to help improve problem-solving skills. Man becomes flawless via practice, and individuals who engage in frequent practice can propose answers to various difficulties. Analytical, technical, logical, methodical, mechanical, procedural, and so on are examples.

Examine how other people solve problems − Observing is a vital method of learning and thoroughly comprehending concepts and elements. It applies to all regions and fields, and this strategy significantly improves problem-solving abilities.

Problem-solving skills are cognitive processes that aim to solve a problem. As we are exposed to various situations with novel problems every second day, many factors prevent a person from finding a solution. The factors that act as hindrances are mental set, functional fixedness, irrelevant information, insight, and resources available. Nevertheless, on the other hand, the facilitating factors are motivation, perception, self-efficacy, and teamwork skills. Even though there are some common factors, due to individual differences, factors might vary in intensity or their presence or absence. Problem-solving skills are very much needed in every stage of life, and these factors can be controlled to facilitate problem-solving skills.

- Related Articles

- Attention and Problem Solving

- Reasoning and Problem Solving

- Problem Solving: Meaning, Theory, and Strategies

- Problem Solving - Steps, Techniques, & Best Practices

- Problem-solving on Boolean Model and Vector Space Model

- Tips for Effective Problem-solving in Quality Management

- How Can Leaders Improve Problem-Solving Abilities?

- Explain The Scientific Method Used By A Scientist In Solving Problem?

- Solving Cryptarithmetic Puzzles

- Sudoku Solving algorithms

- Signals and Systems – Solving Differential Equations with Laplace Transform

- Water and Jug Problem in C++

- Snake and Ladder Problem

- Nuts and Bolt Problem

Kickstart Your Career

Get certified by completing the course

Identifying Barriers to Problem-Solving in Psychology

Problem-solving is a key aspect of psychology, essential for understanding and overcoming challenges in our daily lives. There are common barriers that can hinder our ability to effectively solve problems. From mental blocks to confirmation bias, these obstacles can impede our progress.

In this article, we will explore the various barriers to problem-solving in psychology, as well as strategies to overcome them. By addressing these challenges head-on, we can unlock the benefits of improved problem-solving skills and mental agility.

- Identifying and overcoming barriers to problem-solving in psychology can lead to more effective and efficient solutions.

- Some common barriers include mental blocks, confirmation bias, and functional fixedness, which can all limit critical thinking and creativity.

- Mindfulness techniques, seeking different perspectives, and collaborating with others can help overcome these barriers and lead to more successful problem-solving.

- 1 What Is Problem-Solving in Psychology?

- 2 Why Is Problem-Solving Important in Psychology?

- 3.1 Mental Blocks

- 3.2 Confirmation Bias

- 3.3 Functional Fixedness

- 3.4 Lack of Creativity

- 3.5 Emotional Barriers

- 3.6 Cultural Influences

- 4.1 Divergent Thinking

- 4.2 Mindfulness Techniques

- 4.3 Seeking Different Perspectives

- 4.4 Challenging Assumptions

- 4.5 Collaborating with Others

- 5 What Are the Benefits of Overcoming These Barriers?

- 6 Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Problem-Solving in Psychology?

Problem-solving in psychology refers to the cognitive processes through which individuals identify and overcome obstacles or challenges to reach a desired goal, drawing on various mental processes and strategies.

In the realm of cognitive psychology, problem-solving is a key area of study that delves into how people use algorithms and heuristics to tackle complex issues. Algorithms are systematic step-by-step procedures that guarantee a solution, whereas heuristics are mental shortcuts or rules of thumb that provide efficient solutions, albeit without certainty. Understanding these mental processes is crucial in exploring how individuals approach different types of problems and make decisions based on their problem-solving strategies.

Why Is Problem-Solving Important in Psychology?

Problem-solving holds significant importance in psychology as it facilitates the discovery of new insights, enhances understanding of complex issues, and fosters effective actions based on informed decisions.

Assumptions play a crucial role in problem-solving processes, influencing how individuals perceive and approach challenges. By challenging these assumptions, individuals can break through mental barriers and explore creative solutions.

Functional fixedness, a cognitive bias where individuals restrict the use of objects to their traditional functions, can hinder problem-solving. Overcoming functional fixedness involves reevaluating the purpose of objects, leading to innovative problem-solving strategies.

Through problem-solving, psychologists uncover underlying patterns in behavior, delve into subconscious motivations, and offer practical interventions to improve mental well-being.

What Are the Common Barriers to Problem-Solving in Psychology?

In psychology, common barriers to problem-solving include mental blocks , confirmation bias , functional fixedness, lack of creativity, emotional barriers, and cultural influences that hinder the application of knowledge and resources to overcome challenges.

Mental blocks refer to the difficulty in generating new ideas or solutions due to preconceived notions or past experiences. Confirmation bias, on the other hand, is the tendency to search for, interpret, or prioritize information that confirms existing beliefs or hypotheses, while disregarding opposing evidence.

Functional fixedness limits problem-solving by constraining individuals to view objects or concepts in their traditional uses, inhibiting creative approaches. Lack of creativity impedes the ability to think outside the box and consider unconventional solutions.

Emotional barriers such as fear, stress, or anxiety can halt progress by clouding judgment and hindering clear decision-making. Cultural influences may introduce unique perspectives or expectations that clash with effective problem-solving strategies, complicating the resolution process.

Mental Blocks

Mental blocks in problem-solving occur when individuals struggle to consider all relevant information, fall into a fixed mental set, or become fixated on irrelevant details, hindering progress and creative solutions.

For instance, irrelevant information can lead to mental blocks by distracting individuals from focusing on the key elements required to solve a problem effectively. This could involve getting caught up in minor details that have no real impact on the overall solution. A fixed mental set, formed by previous experiences or patterns, can limit one’s ability to approach a problem from new perspectives, restricting innovative thinking.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias, a common barrier in problem-solving, leads individuals to seek information that confirms their existing knowledge or assumptions, potentially overlooking contradictory data and hindering objective analysis.

This cognitive bias affects decision-making and problem-solving processes by creating a tendency to favor information that aligns with one’s beliefs, rather than considering all perspectives.

- One effective method to mitigate confirmation bias is by actively challenging assumptions through critical thinking.

- By questioning the validity of existing beliefs and seeking out diverse viewpoints, individuals can counteract the tendency to only consider information that confirms their preconceptions.

- Another strategy is to promote a culture of open-mindedness and encourage constructive debate within teams to foster a more comprehensive evaluation of data.

Functional Fixedness

Functional fixedness restricts problem-solving by limiting individuals to conventional uses of objects, impeding the discovery of innovative solutions and hindering the application of insightful approaches to challenges.

For instance, when faced with a task that requires a candle to be mounted on a wall to provide lighting, someone bound by functional fixedness may struggle to see the potential solution of using the candle wax as an adhesive instead of solely perceiving the candle’s purpose as a light source.

This mental rigidity often leads individuals to overlook unconventional or creative methods, which can stifle their ability to find effective problem-solving strategies.

To combat this cognitive limitation, fostering divergent thinking, encouraging experimentation, and promoting flexibility in approaching tasks can help individuals break free from functional fixedness and unlock their creativity.

Lack of Creativity

A lack of creativity poses a significant barrier to problem-solving, limiting the potential for improvement and hindering flexible thinking required to generate novel solutions and address complex challenges.

When individuals are unable to think outside the box and explore unconventional approaches, they may find themselves stuck in repetitive patterns without breakthroughs.

Flexibility is key to overcoming this hurdle, allowing individuals to adapt their perspectives, pivot when necessary, and consider multiple viewpoints to arrive at innovative solutions.

Encouraging a culture that embraces experimentation, values diverse ideas, and fosters an environment of continuous learning can fuel creativity and push problem-solving capabilities to new heights.

Emotional Barriers

Emotional barriers, such as fear of failure, can impede problem-solving by creating anxiety, reducing risk-taking behavior, and hindering effective collaboration with others, limiting the exploration of innovative solutions.

When individuals are held back by the fear of failure, it often stems from a deep-seated worry about making mistakes or being judged negatively. This fear can lead to hesitation in decision-making processes and reluctance to explore unconventional approaches, ultimately hindering the ability to discover creative solutions. To overcome this obstacle, it is essential to cultivate a positive emotional environment that fosters trust, resilience, and open communication among team members. Encouraging a mindset that embraces failure as a stepping stone to success can enable individuals to take risks, learn from setbacks, and collaborate effectively to overcome challenges.

Cultural Influences

Cultural influences can act as barriers to problem-solving by imposing rigid norms, limiting flexibility in thinking, and hindering effective communication and collaboration among diverse individuals with varying perspectives.

When individuals from different cultural backgrounds come together to solve problems, the ingrained values and beliefs they hold can shape their approaches and methods.

For example, in some cultures, decisiveness and quick decision-making are highly valued, while in others, a consensus-building process is preferred.

Understanding and recognizing these differences is crucial for navigating through the cultural barriers that might arise during collaborative problem-solving.

How Can These Barriers Be Overcome?

These barriers to problem-solving in psychology can be overcome through various strategies such as divergent thinking, mindfulness techniques, seeking different perspectives, challenging assumptions, and collaborating with others to leverage diverse insights and foster critical thinking.

Engaging in divergent thinking , which involves generating multiple solutions or viewpoints for a single issue, can help break away from conventional problem-solving methods. By encouraging a free flow of ideas without immediate judgment, individuals can explore innovative paths that may lead to breakthrough solutions. Actively seeking diverse perspectives from individuals with varied backgrounds, experiences, and expertise can offer fresh insights that challenge existing assumptions and broaden the problem-solving scope. This diversity of viewpoints can spark creativity and unconventional approaches that enhance problem-solving outcomes.

Divergent Thinking

Divergent thinking enhances problem-solving by encouraging creative exploration of multiple solutions, breaking habitual thought patterns, and fostering flexibility in generating innovative ideas to address challenges.

When individuals engage in divergent thinking, they open up their minds to various possibilities and perspectives. Instead of being constrained by conventional norms, a person might ideate freely without limitations. This leads to out-of-the-box solutions that can revolutionize how problems are approached. Divergent thinking sparks creativity by allowing unconventional ideas to surface and flourish.

For example, imagine a team tasked with redesigning a city park. Instead of sticking to traditional layouts, they might brainstorm wild concepts like turning the park into a futuristic playground, a pop-up art gallery space, or a wildlife sanctuary. Such diverse ideas stem from divergent thinking and push boundaries beyond the ordinary.

Mindfulness Techniques

Mindfulness techniques can aid problem-solving by promoting present-moment awareness, reducing cognitive biases, and fostering a habit of continuous learning that enhances adaptability and open-mindedness in addressing challenges.

Engaging in regular mindfulness practices encourages individuals to stay grounded in the current moment, allowing them to detach from preconceived notions and biases that could cloud judgment. By cultivating a non-judgmental attitude towards thoughts and emotions, people develop the capacity to observe situations from a neutral perspective, facilitating clearer decision-making processes. Mindfulness techniques facilitate the development of a growth mindset, where one acknowledges mistakes as opportunities for learning and improvement rather than failures.

Seeking Different Perspectives

Seeking different perspectives in problem-solving involves tapping into diverse resources, engaging in effective communication, and considering alternative viewpoints to broaden understanding and identify innovative solutions to complex issues.

Collaboration among individuals with various backgrounds and experiences can offer fresh insights and approaches to tackling challenges. By fostering an environment where all voices are valued and heard, teams can leverage the collective wisdom and creativity present in diverse perspectives. For example, in the tech industry, companies like Google encourage cross-functional teams to work together, harnessing diverse skill sets to develop groundbreaking technologies.

To incorporate diverse viewpoints, one can implement brainstorming sessions that involve individuals from different departments or disciplines to encourage out-of-the-box thinking. Another effective method is to conduct surveys or focus groups to gather input from a wide range of stakeholders and ensure inclusivity in decision-making processes.

Challenging Assumptions

Challenging assumptions is a key strategy in problem-solving, as it prompts individuals to critically evaluate preconceived notions, gain new insights, and expand their knowledge base to approach challenges from fresh perspectives.

By questioning established beliefs or ways of thinking, individuals open the door to innovative solutions and original perspectives. Stepping outside the boundaries of conventional wisdom enables problem solvers to see beyond limitations and explore uncharted territories. This process not only fosters creativity but also encourages a culture of continuous improvement where learning thrives. Daring to challenge assumptions can unveil hidden opportunities and untapped potential in problem-solving scenarios, leading to breakthroughs and advancements that were previously overlooked.

- One effective technique to challenge assumptions is through brainstorming sessions that encourage participants to voice unconventional ideas without judgment.

- Additionally, adopting a beginner’s mindset can help in questioning assumptions, as newcomers often bring a fresh perspective unburdened by past biases.

Collaborating with Others

Collaborating with others in problem-solving fosters flexibility, encourages open communication, and leverages collective intelligence to navigate complex challenges, drawing on diverse perspectives and expertise to generate innovative solutions.

Effective collaboration enables individuals to combine strengths and talents, pooling resources to tackle problems that may seem insurmountable when approached individually. By working together, team members can break down barriers and silos that often hinder progress, leading to more efficient problem-solving processes and better outcomes.

Collaboration also promotes a sense of shared purpose and increases overall engagement, as team members feel valued and enableed to contribute their unique perspectives. To foster successful collaboration, it is crucial to establish clear goals, roles, and communication channels, ensuring that everyone is aligned towards a common objective.

What Are the Benefits of Overcoming These Barriers?

Overcoming the barriers to problem-solving in psychology leads to significant benefits such as improved critical thinking skills, enhanced knowledge acquisition, and the ability to address complex issues with greater creativity and adaptability.

By mastering the art of problem-solving, individuals in the field of psychology can also cultivate resilience and perseverance, two essential traits that contribute to personal growth and success.

When confronting and overcoming cognitive obstacles, individuals develop a deeper understanding of their own cognitive processes and behavioral patterns, enabling them to make informed decisions and overcome challenges more effectively.

Continuous learning and adaptability play a pivotal role in problem-solving, allowing psychologists to stay updated with the latest research, techniques, and methodologies that enhance their problem-solving capabilities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Similar posts.

Exploring the Concept of Social Scripts in Psychology

The article was last updated by Marcus Wong on February 5, 2024. Have you ever found yourself acting in a certain way in social situations…

Uncovering the Meaning of Blind Spots in Psychology

The article was last updated by Dr. Emily Tan on February 8, 2024. Ever find yourself making decisions that seem irrational in hindsight? Or perhaps…

Unveiling Memory Stages: Psychology Experts and the Second Stage

The article was last updated by Rachel Liu on February 5, 2024. Have you ever wondered how your memory works and the different stages it…

Exploring Stress Tests in Evolutionary Psychology

The article was last updated by Ethan Clarke on February 8, 2024. Have you ever wondered why humans behave the way they do? Evolutionary psychology…

Informed Consent in Psychology: Understanding its Gestures and Limitations

The article was last updated by Julian Torres on February 5, 2024. In psychology, informed consent plays a crucial role in ensuring ethical practices and…

Exploring Dr. Spellman’s Contributions to Psychology: What Did He Study?

The article was last updated by Lena Nguyen on February 9, 2024. Have you ever wondered who Dr. Spellman is and what contributions he made…

- Open access

- Published: 25 May 2023

Factors influencing the complex problem-solving skills in reflective learning: results from partial least square structural equation modeling and fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis

- Ying Wang 1 na1 ,

- Ze-Ling Xu 1 na1 ,

- Jia-Yao Lou 1 na1 &

- Ke-Da Chen 1

BMC Medical Education volume 23 , Article number: 382 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5935 Accesses

2 Citations

Metrics details

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development emphasizes the importance of complex problem-solving (CPS) skills in the 21st century. CPS skills have been linked to academic performance, career development, and job competency training. Reflective learning, which includes journal writing, peer reflection, selfreflection, and group discussion, has been explored to improve critical thinking and problem-solving abilities. The development of various thinking modes and abilities, such as algorithmic thinking, creativity, and empathic concern, all affect problem-solving skills. However, there is a lack of an overall theory to relate variables to each other, which means that different theories need to be integrated to focus on how CPS skills can be effectively trained and improved.

Data from 136 medical students were analyzed using partial least square structural equation modeling (PLSSEM) and fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). A hypothesized model examining the associations between the CPS skills and influence factors was constructed.

The evaluation of the structural model showed that some variables had significant influences on CPS skills, while others did not. After deleting the insignificant pathways, a structural model was built, which showed that mediating effects of empathic concern and critical thinking were observed, while personal distress only had a direct effect on CPS skills. The results of necessity showed that only cooperativity and creativity are necessary conditions for critical thinking. The fsQCA analysis provided clues for each different pathway to the result, with all consistency values being higher than 0.8, and most coverage values being between 0.240 and 0.839. The fsQCA confirmed the validity of the model and provided configurations that enhanced the CPS skills.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that reflective learning based on multi-dimensional empathy theory and 21 stcentury skills theory can improve CPS skills in medical students. These results have practical implications for learning and suggest that educators should consider incorporating reflective learning strategies that focus on empathy and 21 stcentury skills to enhance CPS skills in their curricula.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

When putting forward the theoretical framework of skills and competencies in the 21st century, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development takes complex problem-solving (CPS) skills as an important component and brings them into the evaluation system of the Program for International Student Assessment [ 1 ]. Previous research results have proved that there is a significant positive correlation between CPS skills and academic performance [ 2 ], that is, the stronger the problem-solving skill, the better the academic performance. Similarly, it is also considered to have a great influence on career selection [ 3 ], career development [ 4 ], and job competency training [ 5 ]. Therefore, the improvement of the above-mentioned comprehensive qualities, such as learning ability and post competence, and the cultivation of CPS skills, has been emphasized by a variety of teaching strategies, such as problem-based learning (PBL) [ 6 ], context-based learning (CBL) [ 7 ], situational simulation [ 8 ], and reflective learning [ 9 ].

As an important process of metacognition, reflective learning is closely related to CPS skills. Gadbury-Amyot et al. claimed that the use of reflection and writing as educational strategies to promote critical thinking and problem-solving is one of the best ways for students to express their thought processes [ 10 ]. Exploration to improve CPS skills based on reflective learning and training can be seen in medicine, computer science, mathematics, and other industries. According to Bernack, establishing problem-solving training courses could feasibly enhance the abilities of pre-service teachers [ 11 ]. Kellogg suggested that reflection and writing, as educational strategies to promote critical thinking and problem-solving skill, is one of the best ways to improve students’ expression ability and logical thinking [ 12 ]. “Reflective learning” is a common way of exploring problems and solutions in the deliberative environment, a process of learning through experience, and is a necessary learning tool in professional education [ 13 ]. Reflective learning includes journal writing, peer reflection, self-reflection, and group discussion under the guidance of teachers [ 14 ]. Illeris suggested that the result of reflective learning spans cognitive, psychodynamic, and social-societal dimensions [ 15 ]. Through its influence on students’ behavior, thoughts, and emotions, it realizes the training and improvement of students’ various abilities. It has gradually developed into a more efficient and autonomous learning model and has become an indispensable educational and learning tool for many professionals [ 16 ]. Many experts suggest that the implementation of reflective learning can improve students’ critical thinking [ 17 ], insight [ 18 ], empathic concern [ 19 ], computational thinking [ 20 ], and other skills, and this improvement of a variety of thinking modes and abilities will eventually lead to improvement of their CPS skills [ 21 ]. Our research on the factors affecting the CPS skills is based on reflective learning.

The purpose of human problem solving is to promote the understanding of human thinking through a detailed investigation of the way people solve difficult problems, such as logic or chess. Unlike computer simulations, human problem solving is influenced by psychological factors that cannot be ignored [ 22 ]. Therefore, problem solving is dynamic and needs to consider the influence of speculation, social background, and culture, while CPS skills emphasize the process of successful interaction between the problem solver and the dynamic task environment [ 23 ]. CPS skills are collections of self-regulating psychological processes necessary in the face of complex and dynamic non-routine situations across different domains [ 24 ], and comprises a combination of skills, abilities, motivation, and other psychological structures [ 25 , 26 ]. The factors that impact CPS skills are complex and include cognitive and non-cognitive factors. Research shows that the development of a variety of thinking modes and abilities, such as algorithmic thinking, cooperativity, creativity, critical thinking, personal distress, fantasy, perspective-taking, and empathic concern, all affect the problem-solving skill in varying degrees [ 27 , 28 ]. Among them, empathetic concern and critical thinking have been proven to affect problem-solving skill by many studies. After comprehensively exploring the emerging research on the impact of the factors on the CPS skills, we found that previous studies mainly focused on a single causality in the improvement of problem-solving skill, while there is a lack of overall theory to relate variables to each other, which means that we need to integrate different theories to advance existing research and focuson how CPS skills can be effectively trained and improved.

Theoretical background

The literature analysis of CPS skills reveals the current research status. Based on the relevant theories of skills needed in the 21st century [ 1 ], individuals use analytical, reasoning, and cooperative skills to identify and solve problems consistent with their areas of interest [ 29 ]. Kocak proposes that problem-solving skills are shaped by algorithmic thinking, creativity, cooperativity, critical thinking, digital literacy, and effective communication, and develops a model with critical thinking as a mediating factor [ 21 ]. Developing solutions for complex problems is a complicated process, and individuals require critical thinking skills [ 21 , 30 ] to do so. Critical thinking often occurs at the same time as CPS skills and is one of the core objectives of general education in all subjects of higher education [ 29 ]. Critical thinking, closely related to reflective learning [ 17 ], which has been emphasized in many studies, especially in the implementation of learning strategies including reflective learning. In problem-based learning and case-based learning, instructors encourage learners to use critical reflection to engage with subject matter and to develop their own practice in closing any knowledge gaps that may exist [ 31 ]. Additionally, digital literacy involves the ability to assess the accuracy and value of online resources [ 32 ]. In this study, reflective learning was the primary learning strategy [ 33 ]; therefore, digital literacy skills were not observed in detail. Drawing on the above analysis, we developed a theoretical model that identifies algorithmic thinking, creativity, and cooperativity as antecedents, and critical thinking as an intermediary variable that influences CPS skills.

Another major area related to affecting CPS skills is empathic concern. The research suggests that students with a higher level of cognitive empathy show more positive attitudes and deal with problems more effectively [ 34 ]. In essence, empathetic concern fosters values, beliefs, attitudes, and assumptions, and affect the CPS skills from the perspective of execution [ 35 , 36 ]. Some studies suggest that reflective learning improves empathy [ 37 ]. Based on Davis’s Interpersonal Reactivity Index [ 38 ], empathy was divided into four dimensions mentioned: Empathic concern, fantasy, perspective-taking, and personal distress. Nevertheless, some scholars disagree that personal distress belongs to the category of empathy. Personal distress is defined as an over-arousal caused by the lack of boundaries between oneself and others [ 39 , 40 ]. Some studies show that personal distress leads to egoism and overwhelms altruistic activities mediated by empathetic concern [ 41 ]. And there is a statistically significant correlation between personal distress and empathetic concern [ 42 ]. Therefore, we still adhere to the view that the two cannot be regarded as mutually exclusive emotions, bringing personal distress into the scope of our research and exploring its role in CPS skills. Empathetic concern has been proved to associate with prosocial behavior [ 43 ]. In the relationship between empathic concern and prosocial concern, empathic concern elicits an approach orientation toward the target [ 44 ] and is used as a mediator variable in some models. For example, some studies consider empathic concern and personal distress are both mediators of perspective-taking to helping behavior [ 45 ]. Based on the above analysis, we built our theoretical model and assume that personal distress, perspective-taking, and fantasy as antecedents and empathetic concern as intermediary variables that affect the CPS skills.

Above all, the empathic concern and the critical thinking are two remarkable characteristics of the CPS skills, which can play a common role in the CPS skills [ 46 ], however, there is a lack of overall theory to connect them, which means that different theories need to be integrated to promote research. The comprehensive study of the combination of the two aspects can better understand how to improve CPS skills, which cannot be provided by any theory alone. Moreover, the results on the factors affecting the CPS skills also show some inconsistencies. For example, Batson believes that personal distress in empathy inhibits the development of problem-solving skills [ 41 ], whereas Mora disagrees [ 47 ]. A possible reasonable explanation for these contradictory results is that the previous studies on the factors influencing problem-solving skill mainly adopted traditional symmetric methods (such as regression and SEM), which did not fully capture the complexity of the factors that influence problem-solving skills, and the factors affecting the CPS skills are often based on multiple causalities rather than a single causal relationship. Simply evaluating symmetric relationships might lead to divergent results, thus masking the complexity of the problem-solving skill. Considering the complex nature of CPS skills under the condition of reflective learning, it is necessary to check the symmetric and asymmetric relationships between structures to fully understand the strategies and methods to improve CPS skills, therefore, PLS-SEM [ 48 ] and fsQCA [ 49 ] were used in our study comprehensively.

Research model and hypothesis development

Designing the pls-sem research model.

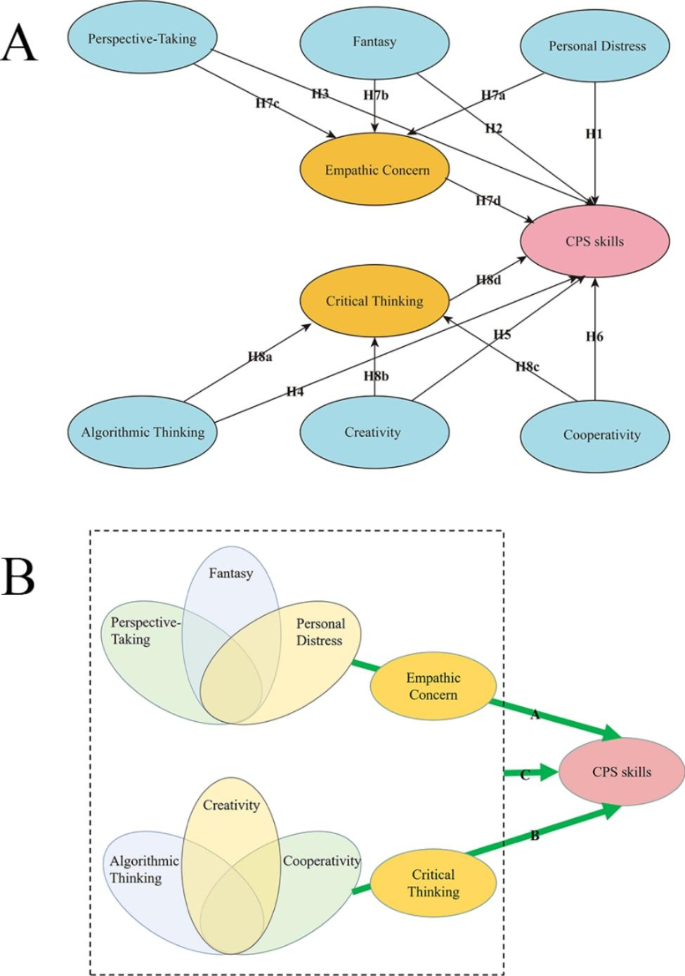

Critical thinking in the field of cognition and empathic concern in the field of emotion are representatives of two different thinking modes affecting the CPS skills. PLS-SEM assumes that fantasy, perspective-taking, personal distress, algorithmic thinking, creativity, and cooperativity have a direct impact on the CPS skills. Empathetic concern and critical thinking play an intermediary role between these relationships and the CPS skills (Fig. 1 A).

Partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) conceptual model and fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) conceptual model: ( A ) The PLS-SEM conceptual model. ( B ) The fsQCA conceptual model

Personal distress and CPS skills

The definition of personal distress in this study pertains to the discomfort and anxiety that respondents experience when observing negative experiences of others, including fear, apprehension, and discomfort. Personal distress is an aspect of emotional empathy [ 38 ]. Some studies show that personal distress and empathy are complex and dynamic emotional experiences [ 50 ]. Personal distress, as an indicator of self-other differentiation and emotional regulation, is a kind of negative emotion. Excessive personal distress can lead to emotional regulation and interpersonal difficulties [ 51 ]. These studies advocate reducing personal distress to relieve stress [ 52 ]. The healthcare sector prioritizes a patient-centered healthcare model, which mandates that we respond to patients’ emotional distress with this principle in mind. However, in practice, health professionals tend to regard emotional health problems as “routine”; therefore, it is necessary to put patients’ emotional and identity issues in the dominant position of the marginal biomedical model used by health professionals [ 53 ]. However, empathic pain is crucial to Hoffman’s moral development framework. He believed that pain can cause significant effects that might lead to action [ 54 ]. Moitra’s research also supports the positive effect of personal distress on problem-solving skill [ 47 ]. Reflection encourages individuals to confront their own embarrassing and uncomfortable past experiences, learn from their errors, and enhance their CPS skills [ 55 ].

Fantasy and CPS skills

Fantasy acts on all aspects of reflective learning. First, to some extent, our brains process information and decisions in an irrational way, and reflection contributes to the cultivation of irrational thinking [ 56 ]. The improvement of subjects’ irrational thinking, including fantasy, can be promoted through reflective learning. Research indicates that individuals with higher fantasy and perspective-taking skills tend to have stronger social understanding [ 57 ]. Second, the development of imagination and fantasy is an important part of cultivating empathic concern [ 58 ]. This is because people understand the world through fantasy, and fantasy gives people hope that the world will become a better place [ 59 ]. For example, Melissa McInnis Brown’s research showed that children who play using fantasies are better at sharing emotions than their peers [ 60 ]. Many studies have proven the role of fantasy in problem-solving. For example, David Weibel pointed out that one can effectively use imagination in an environment, such as in artistic expression or problem-solving [ 61 ]. Fantasy is an imaginative way to find creative solutions that can help people predict the realization of creative structures [ 61 ]. From a sociological point of view, scholars usually regard fantasy as an important factor in cultivating children’s prosocial behaviour [ 57 , 62 ]. Empathic concern requires a person or the whole team to have an overall and largely unconscious “feeling” in terms of emotions, body language, previous experiences, and interpersonal relationships; therefore, this requires significant support from the fantasy system [ 63 ].

Perspective-taking and CPS skills

The effectiveness of group problem solving heavily depends on group member interactions and group composition. For perspective-taking, it provides the possibility for effective communication, which mainly affects the effective presentation of information, effective understanding of that information, conflict resolution, and cooperative interaction [ 64 , 65 ]. In management, perspective-taking has become an important factor in teamwork to solve problems [ 66 ]. During perspective-taking, the problem-solving process can be facilitated by promoting empathic concern, which is evident in the subjects’ cognitive dimension. For example, Falk found that perspective-taking leads to more creative solutions, and team members are more cooperative and facilitate more effective communication [ 64 ]. Bethune and Brown suggested that reflection affects the professional identity of patients by encouraging personal insights and providing different perspectives on patient interaction [ 67 ]. Reflection requires us to think about the past and sum up experiences and lessons from it. Thinking about problems from the standpoint of others can circumvent the limitations of our perspective of looking at problems only through ourselves and can promote the solution of complex problems.

Based on the points discussed above, we propose the following assumptions:

Personal distress is positively related to the CPS skills.

Fantasy is positively related to the CPS skills.

Perspective-taking is positively related to the CPS skills.

Algorithmic thinking and CPS skills

Algorithm thinking draws lessons from the algorithms of computers and artificial intelligence, which enables people to think and deal with things in parallel, process things in data, carry on data and logical reasoning to things, and finally achieve the goal of completing plans and tasks. As one of the core skills in the 21st century, algorithmic thinking abstractly and logically determines the elements used to solve problems through analysis [ 28 ]. One of the major applications of algorithmic thinking is jigsaw puzzle-based learning, which aims to make subjects think about how to build and solve problems, and improve their critical analysis and problem-solving skills [ 68 ]. Hasan Gürbüz leveraged straightforward visual and language templates to help individuals develop models and analyze information about events through games, resulting in improved problem-solving skills [ 69 ]. This mode of thinking, based on logic and steps, is very important for the development of critical thinking and computational thinking [ 28 ]. Many studies have shown that there is a positive correlation between algorithmic thinking and critical thinking [ 70 ]. In reflective learning, algorithmic thinking plays a significant role in computing, as evidenced in this study by recording a short video that necessitates organizing large amounts of data to develop suitable algorithms for analysis [ 71 ].

Creativity and CPS skills

Creativity affects our lives and is vital to the progress of society [ 72 ]. The definition of creativity highlights the integration of novel (original, unexpected) and appropriate (useful, adaptive concerning task constraint) ideas [ 73 ]. Since the 20th century, a large number of scholars in various fields have paid attention to creativity and CPS skills. Creativity is a valuable skill while designing solutions to new challenges that arise in developing societies [ 74 ]. For instance, Garrett noted that creativity plays a crucial role in problem-solving [ 75 ]. In many studies, creativity and critical thinking are interdependent, and creative tasks can improve people’s creativity [ 76 ]. In reflective learning, we utilize divergent thinking that frequently enhances our creativity.

Cooperativity and CPS skills

Many critics believe that cooperativity plays an important role in the cultivation of critical thinking [ 77 ]. Cooperativity receives considerable attention in the learning process due to its association with effective communication. For example, service-learning attaches great importance to cooperation, democratic citizenship, and moral responsibility in the learning process [ 78 ], and preschool educational institutions need to improve the experience through the collaborative exchange, to create favorable conditions for educators to re-examine educational activities, and determine the direction of new relationships through observation [ 79 ]. In reflective learning, subjects become aware of their contradictions and gain valid information, and critically assess peer opinions through active communication, which advances their ideas for program and CPS skills improvement.

Algorithmic thinking is positively related to the CPS skills.

Creativity is positively related to the CPS skills.

Cooperativity is positively related to the CPS skills.

Mediators and CPS skills

This study assumes that empathetic concern and critical thinking act as mediators between the CPS skills and their antecedents.

In Gibbs’s theory, the emotional dimension is a very important aspect of reflective learning [ 80 ]. Madeline Kelly’s research showed that reflection has a positive effect on the improvement of cognitive empathy [ 81 ]; however, there are few studies on the effect of reflective learning on empathy. Cognitive empathy includes fantasy and perspective-taking, while the emotional empathy includes personal distress and empathic concern [ 82 ]. Research shows that the concept of emotional empathy is state empathy, with the focus on altruism [ 83 , 84 ]. Emotional empathy plays an important role in patient-nurse communication [ 85 ]. Failure to deal with or understand emotions will make it difficult for nurses to think rationally and critically about issues that are important to nursing practice [ 86 ]. Therefore, we cannot ignore the influence of empathic concern on the CPS skills in reflective learning. We assumed that the ability of empathic concern can increase altruism and help to improve CPS skills. However, personal distress is usually considered to lead to egoism, which is not conducive to the formation of altruism [ 41 ]. In-depth investigation is necessary to understand its effect on CPS skills. As an important factor in prosocial behavior, the empathic concern serving as a mediator between cognitive behavior and prosocial behavior [ 87 ]. Based on the theories of O’Brien and Gülseven, we constructed a CPS skills model with empathic concern as the mediating variable [ 88 , 89 ].

Effective reflection is characterized by purposeful, focused, and questioning [ 90 ]. In the process of reflection, this mode of thinking requires us to think critically and center on the results. Reflective learning, also known as critical reflection [ 17 ], emphasizes the use of critical thinking. Many critics affirm the results of critical reflection [ 91 , 92 , 93 ]. Parrish and Crookes found that among nursing graduates, reflection helped them to solve problems through thoughtful reasoning and to develop strategies for self-monitoring of their professional competence [ 94 ]. Critical thinking is typically rational thinking, and through combining theory with practice, exploring the similarities and differences between theoretical knowledge and practical experience, and considering a variety of different viewpoints and opinions, the effect of reflective learning can be enhanced. Therefore, speculative reflection is designed to help us identify our shortcomings and think about how to correct and improve them. Critical thinking is widely recognized as an important skill in mediating CPS skills [ 10 ]. Based on the research of Kocak and Tee, we also view critical thinking as an intermediary variable, playing a mediating role in algorithmic thinking, creativity, and cooperativity within CPS skills [ 21 , 95 ].

Personal distress indirectly affects the CPS skills through empathic concern.

Fantasy indirectly affects the CPS skills through empathic concern.

Perspective-taking indirectly affects the CPS skills through empathic concern.

Empathic concern is positively related to the CPS skills.

Algorithmic thinking indirectly affects the CPS skills through critical thinking.

Creativity indirectly affects the CPS skills through critical thinking.

Cooperativity indirectly affects the CPS skills through critical thinking.

Critical thinking is positively related to the CPS skills.

Designing the fsQCA configuration model

In this study, a Venn diagram is used to design the fsQCA configuration model (Fig. 1 B), which was used to explore the causal model for improving CPS skills. In the diagram, arrow A represents a combination of perspective-taking, fantasy, and personal distress, and adds configurations that affect the CPS skills through, or including, empathetic concern. Arrow B represents a combination of algorithmic thinking, creativity, and cooperativity, and adds configurations that affect the CPS skills through, or including, critical thinking. Arrow C represents the combination of all the variables and represents the complex interaction of these factors to predict the resulting conditions.

Participants

Participants were 136 freshmen and medical majors from a university in southeastern China (‾Xage = 18.47, female = 82.35%, male = 17.65%). The inclusion criterion comprised students who had conducted reflective learning. The exclusion criteria comprised: (1) Students who did not make reflective videos, or (2) students suspected of plagiarizing reflective learning achievements. A total of 163 cases were included in the empirical study of reflective learning, and 136 effective samples were recovered, with an effective recovery rate of 83.44%.

Design and procedure

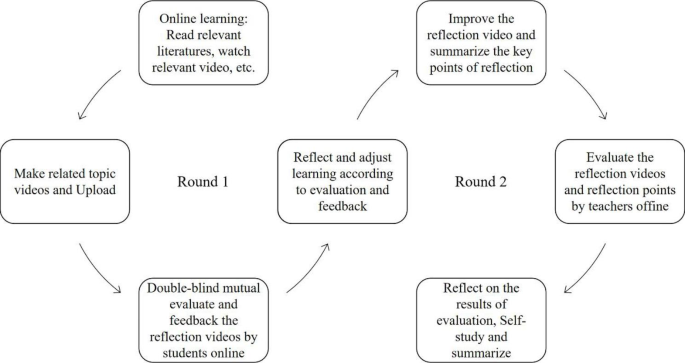

After receiving appropriate online training, classroom teachers implemented a reflective learning curriculum design among medical students in the autumn of 2021 (Fig. 2 ). Based on the Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Courses, the two rounds of teaching plan lasted a total of 14 weeks was design. In the first round of reflective learning, subjects were asked to read relevant literature, watch relevant video materials, etc., and carry out online learning. They were then asked to record learning videos on their own, and then upload the videos, followed by a double-blind mutual evaluation of learning videos between online students. In the second round of reflective learning, students adjusted their reflective learning according to the feedback from the previous round of mutual evaluation, implemented a second round of deeper material learning exploration, improved their reflective video, and summarized the main points of reflective learning. Teachers evaluated the reflective videos and learning points offline, and students learned and summarized according to the evaluation results. After the end of the entire process, we issued a competency assessment questionnaire to measure learners’ competency levels and the data was collected.

Reflective learning process

To measure the constructs under study, existing scales were used (see Table 1 for items associated with each construct and scale reliabilities).

A questionnaire was developed based on the existing mature scale, and the items were slightly adjusted according to the model. The relationship between the retained items and the dimensions was not complementary. Improvement of CPS skills is described as a structure composed of six antecedent variables and two mediating variables with different ways of thinking. The Davis Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) was used for personal distress, fantasy, perspective-taking, and empathic concern [ 38 ], and the Computational Thinking Scale (CTS) was used for critical thinking, algorithmic thinking, creativity, problem solving, and cooperativity [ 74 , 96 , 97 ]. We structured it as personal distress (three items), fantasy (three items), and perspective-taking (two items) as ante-dependent variables, and the mediating effect of empathic concern (three items) on CPS skills (three items) was directly and through empathic concern (3 items). Similarly, algorithmic thinking (3 items), creativity (three items), and cooperativity (three items) acted as ante-variables, both directly and through the mediating effect of critical thinking (three items). All items were evaluated using a Likert 5-point scale, 5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 2 = disagree, 1 = strongly disagree, and the scores of items in reverse scoring were reversed. Entries for reverse scoring are marked with * in Table 1 . The questionnaire was translated into Chinese and distributed after discussion with experts.

Data analysis

We use multiple methods to analyze the data. First, PLS-SEM was carried out on the data through Smart-PLS 3.0 software to adapt the complex model analysis and explore the impact of various factors [ 48 ].

We measured the characteristics of the structure using internal consistency reliability, convergence validity, and discrimination validity. Internal consistency reliability was measured using the alpha and combinatorial reliability of Cronbach. And we checked the collinearity of the internal model and evaluated the deviation of the method using a variance inflation factor (VIF). According to the research objectives, we tested two models with different paths with significant correlations. The direct predictive effects of fantasy, personal distress, perspective-taking, creativity, cooperativity, and algorithmic thinking, as well as the mediating effects of empathic concern and critical thinking, on CPS skills were tested. A nonparametric, bias-corrected bootstrap with 5,000 subsamples and a 95% confidence interval was used. The structural model was evaluated by R² and by the significance of the estimated value of pathway relationships. The significance of pathway coefficients was evaluated using the bootstrap subsamples, and the structural model was evaluated using 5000 bootstrap subsamples [ 98 ]. R² values of 0.25, 0.50, or 0.75 are considered weak, moderate, and significant, respectively.

Although PLS-SEM can handle both external (measurement) and internal (structural) models [ 98 ], it is limited by symmetry. Therefore, we used fsQCA 3.1 software [ 49 ] to analyze asymmetry and obtain a sufficient causal combination configuration to study the complex relationship between variables more comprehensively and in detail. According to the fsQCA user guide, data calibration, truth table construction, and causal condition analysis are necessary steps in the process of data analysis [ 49 ]. In the first step, we converted the ordinary data into fuzzy sets by setting the original values from the Likert scale, which corresponded to full membership, cross-over anchors, and full non-membership based on Kallmuenzer’s analysis [ 99 ]. The second step is to construct the truth table and generate different combinations of causal conditions that are sufficient to affect the CPS skills by specifying a consistent cutoff value as the natural breakpoint in the consistency and the case number threshold as 1. The third, we analyzed the necessity of all the variables (critical thinking, creativity, algorithmic thinking, cooperativity, empathetic concern, perspective-taking, personal distress and fantasy) to the CPS skills, and the antecedent variables for mediate variables (critical thinking and empathic concern), and the necessity of mediating variables to the outcome variables. It is generally believed that a condition or combination of conditions is “necessary” or “almost always necessary” when the consistency score is higher than 0.9 [ 49 ]. Finally, we use standard analysis to obtain “intermediate solutions” (i.e., partial logical remainders are incorporated into the solution) to identify causal patterns that affect CPS skills.

The result of PLS-SEM

Evaluation of the reflection measurement model.

Except for the perspective-taking, the Cronbach’s alpha in the other dimensions was generally more than 0.7, reaching the standard recommended by Cohen (Table 1 ) [ 100 ]. After examining the external loads in the external model, we observed that most of the loads were more than 0.7, while the PD1 project was still less than 0.7. After checking the Cronbach’s alpha and average variance extracted (AVE), we confirmed that this factor had no negative effect on our research [ 98 ], and was thus retained the project. The sample size of the model is small (less than 300), and the items considered by perspective-taking are 2 (less than 3), so Cronbach’s alpha is easily less than 0.6. The alpha of perspective-taking is more than 0.5, which is still in a slightly plausible range. Therefore, we kept the item of perspective-taking. Secondly, the square root of AVE was greater than 0.5, which accords with the convergence validity [ 101 ]. In addition, we used the Fornell-Larker criteria to evaluate the discriminant validity (Table 2 ).

Evaluation of formative measurement models

The results showed that the VIF of all constructs was lower than the threshold of 3.3 (see Additional file. 1 ) [ 98 ]. In order to further analyze, this study evaluated the quality by blindfolding program (Q 2 ) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The results showed that SRMR = 0.079, not exceeding 0.09 [ 102 ]. The blindfold program showed that Q 2 was greater than 0, which verified the predictive correlation of the research model [ 103 ].

Structural model evaluation

Evaluation of the structural model showed that the R² value was reasonable for exploratory research. Meanwhile, the direct pathway effect of fantasy, algorithmic thinking, creativity, and cooperativity on CPS skills was not significant ( p > 0.05), and the pathway effect of personal distress on empathic concern was also not significant ( p > 0.05). The other variables showed significant influences on CPS skills ( p < 0.05) (Table 3 ). After deleting the insignificant pathways, we built a structural model between the CPS skills and the influencing factors (critical thinking, cooperativity, creativity, algorithmic thinking, empathic concern, fantasy, perspective-taking, and personal distress) (Fig. 3 ). Compared with the hypothetical model, mediating effects of empathic concern and critical thinking were observed; however, personal distress only had a direct effect on CPS skills, which was consistent with the previous view that empathic concern and personal distress should be discussed [ 51 ].

Path model and partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) estimates

The result of fsQCA

The results of necessity showed that only cooperativity and creativity are necessary conditions for critical thinking (see Additional file. 2 , Additional file. 3 , and Additional file. 4 ).

FsQCA assessed the complex causal combination that led to improved CPS skills (Tables 4 , 5 , 6 and 7 ). The solution provided clues for each different pathway to the result, with all consistency values being higher than 0.8, and most coverage values being between 0.240 and 0.839 [ 104 ].

As shown in Table 4 , there are six approaches to the final model of complex conditions that lead to high CPS skills, among which the top three in terms of coverage are: (1) To achieve high CPS skills through high critical thinking, cooperativity, creativity, algorithmic thinking, empathic concern, personal distress, and perspective-taking (consistency = 0.974, coverage = 0.354). (2) Under conditions of high critical thinking, cooperativity, algorithmic thinking, and creativity, combined with high empathic concern, personal distress, and fantasy, the CPS skills can be improved (consistency = 0.950, coverage = 0.352). (3) A high level of critical thinking, cooperativity, algorithmic thinking, creativity, personal distress, perspective-taking, and fantasy (consistency = 0.950, coverage = 0.340) can promote the improvement of CPS skills.

To examine the mediating effect of empathic concern and critical thinking on the CPS skill, we analyzed the complex causality of fantasy, personal distress, perspective-taking, and empathic concern. The results showed in Table 5 indicated that the complex causal statement of fantasy, personal distress, perspective-taking, and empathic concern is one way, i.e., high perspective-taking and fantasy improves empathic concern skill (consistency = 0.821; coverage = 0.612), which supports the H7b and H7c assumptions in the SEM model. By contrast, the results of analyzing the complex causal relationship of creativity, cooperativity, and algorithmic thinking for critical thinking showed that there is a pathway for the complex causal statement of creativity, cooperativity, algorithmic thinking, and critical thinking (consistency = 0.867, coverage = 0.760), which will lead to improved critical thinking ability. This supported the hypotheses of H8a, H8b, and H8c in the SEM model.