Here's What Happened To The Murder Hornets In Washington State

Starting in late 2019, reports of murder hornets caused a stir, but those reports have since died down. Here's what happened to the murder hornets since then.

What Types Of Earthquakes Cause Tsunamis?

Tsunamis are devastating natural disasters, but they're also rather rare. They require specific circumstances, but some earthquakes can provide just that.

11 Telltale Signs That Someone Is A Narcissist

Everyone has dealt with someone who is overly arrogant or selfish, but are they a narcissist? There are a few specific traits you can look for to answer that.

These 11 Habits Make You More Likely To Die Early

Plenty of people are invested in finding ways to live longer, but there are plenty of familiar habits that work against that goal. Here are a few of them.

More Stories

The Quantum Cat Experiment That Broke An Incredible Record

A quantum cat might sound like something out of science fiction, but it's actually quite real. And this experiment managed to push the concept to new heights.

The Biggest Known Structure In The Universe And How Far It Is From Earth

Space is a big place filled with plenty of mysteries, and even the largest known object in the universe still leaves some scientists perplexed.

The Big Change To Earth's Atmosphere That's Causing Extreme Weather

Extreme weather is an increasingly common problem around the world, and changes to this atmospheric phenomenon could just make things even worse.

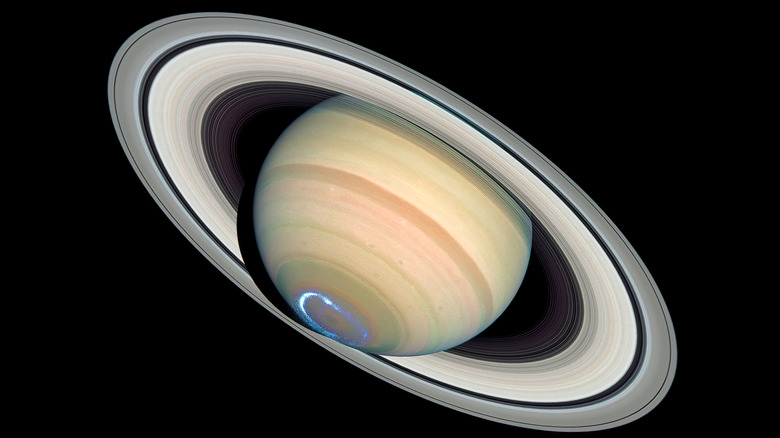

What Auroras Look Like On Other Planets In Our Solar System

Auroras are beautiful phenomena on Earth, but they aren't specific to this planet. In fact, they appear on many other planets, and they're equally spectacular.

Octopuses Have Three Times As Many Brains As They Have Hearts

Octopuses are pretty weird animals that are constantly surprising us. They have a strange number of hearts, but they have an even weirder number of brains.

Fool's Gold In New York Actually Hid A Surprising Treasure

Fool's gold is known for being a deceptive little mineral, but that hasn't always been true. A discovery made in New York proved just how valuable it could be.

Top 5 Most Dangerous Species In Florida

The U.S. is home to a fair few scary species, and Florida is home to quite a number of them. Here are five of the most dangerous animals that reside there.

The Hard Math Problem That Stumped Einstein

Albert Einstein may be considered the greatest mind of the 20th century, but that doesn't mean he couldn't be stumped by the occasional math problem.

The Best Wildlife By Continent: The Earth's Most Biodiverse Ecosystems Ranked

Each continent has its own share of different species, but not all of them are created equal. Here's a rundown of which continents are the most biodiverse.

The Largest Science Museum In The Western Hemisphere Is Actually In Illinois

Museums all have the goal of sharing information, but if you're looking for a standout, the largest science museum in the Western Hemisphere is a good start.

The Different Types Of Northern Lights Explained

The northern lights are quite the beautiful and fascinating natural phenomenon, but did you know that there's a reason they look the way they do?

5 Invasive Species That Are Wreaking Havoc In Indiana

Invasive species have the capability of heavily damaging the ecosystems they find themselves in. That's true all across the U.S., and Indiana is no exception.

The Unassuming New Mexico Lake That's Actually A Death Trap

Diving has quite a bit of allure for thrill seekers, and this lake in New Mexico is especially appealing for that. But it also has quite a dark history.

Washington State Has The Deadliest And Most Destructive Volcanic Eruption In US History

When it comes to volcanic eruptions, most people picture smoke, ash, and lava. Not all eruptions are quite so destructive, but this was certainly was.

How High Relative Humidity Impacts Your Body (& Why It Feels More Miserable Than Dry Heat)

It's never a surprise to hear someone complaining about humidity, but is there a reason it's so much worse than dry heat? Here's the science behind that.

5 Invasive Species That Are Wreaking Havoc In California

Invasive species have the ability to damage ecosystems, and that's especially true in California, where these five species threaten the state's biodiversity.

The 12 Best Peptides To Improve Your Body

If you've ever looked for health supplements, you've probably heard of peptides. Research on is still ongoing, but here are some of the most promising ones.

The Invasive Species That's Destroying The Florida Everglades

Invasive species can often cause major problems for the ecosystems around them, and that's proven very true of this species that's made its home in Florida.

The Milky Way Is Colliding With Another Galaxy. Here's What You Should Know

The Milky Way seems to be currently colliding with one of its galactic neighbors, and that discovery might change how we think of space on the whole.

It Would Take A Staggering Amount Of Time To Travel To The Farthest Planet From Earth In Our Solar System

It's no surprise that space is massive, but even getting to the furthest planet from Earth within our own solar system would take longer than you might expect.

Silicon Vs. Silicone: How Each Material Is Used

Scientific terms can sometimes look frustratingly similar, as is the case for silicon and silicone. But the two materials are very different, and this is how.

When Was The Last Tsunami To Hit California And Could It Happen Again?

California may be known for earthquakes, but what about another kind of natural disaster? After all, tsunamis have quite the history with the California coast.

Roswell, New Mexico Should Be Famous For More Than Just Aliens

Aliens are a point of fascination for many people, and Roswell is fittingly famous for its UFO stories. But there's another reason the city should be famous.

The Predators That Consumed Over 10 Million Fish In Mere Hours

There's a lot going on in the ocean that's still unexplained, including the exact mechanisms behind this predation event that involved millions of fish.

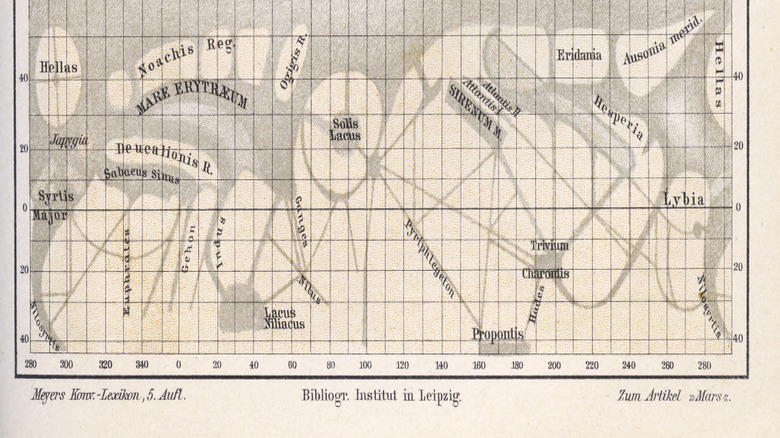

Canals On Mars: The Complicated Truth About Martian Climate Change

Apparent canals on Mars has been an exciting topic at different points in history, and they might actually allow an interesting peek into the planet's past.

Here's Why Stem Cells Grown In Space Have Doctors And Medical Researchers So Excited

Both space exploration and stem cells have been at the center of major research projects, and combining the two has led to a fascinating discovery.

Wyoming Has A Terrifying Secret Below Yellowstone

Yellowstone is a beloved natural wonder, but beneath that beautiful exterior, the park houses a scary secret. In fact, it even has a surprisingly violent past.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Mendelian inheritance is a term arising from the singular work of the 19th-century scientist and Austrian monk Gregor Mendel. His experiments on pea plants highlighted the mechanisms of inheritance in organisms that reproduce sexually and led to the laws of segregation and independent assortment.