- Professional development

- The TeachingEnglish podcast

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into English language teaching?

In episode 7 Chris and We'am are talking to Paul Dummett and Graham Crookes about critical thinking. Together they explore what critical thinking is and how we can integrate it into our lessons.

Series 3, episode 7: What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into English language teaching?

This week, Chris and We'am discuss critical thinking – what does it mean, why is it important and what role does it have to play in English language teaching? Chris and We’am start by talking about critical thinking as a mindset rather than as a skill separate to other learning. First up, they talk to Paul Dummett , who helps define what we mean by critical thinking before going on to discuss its practical role in ELT. In our second interview, Chris and We’am talk to Graham Crookes . They discuss how small changes can be made within the language classroom to make room for critical thinking. We also link back to a previous episode where Chris and Rose Aylett look at the role of micro-resistances in a classroom setting.

Show notes and transcripts in English and Arabic are available to download at the bottom of this page.

How to listen

You can download the episode below or listen on the following platforms:

- Apple Podcasts

You can also search for 'British Council: TeachingEnglish' wherever you get your podcasts, or paste the following URL into your podcast platform: https://feeds.captivate.fm/british-council-teach/

Don't forget to subscribe!

Production team

- Hosts: We'am Hamdan and Chris Sowton

- Producer: Elizabeth Dyer

- Executive producer: Kris Dyer

Are you enjoying the podcast?

Tell us what you think about this episode in the comments below!

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into Engli

I found it very interesting and helpful for English teachers and I want to say thank you so much to the staff due to their supporting

- Log in or register to post comments

Hi xuannhat0901

Thanks for your feedback on the episode - we're very glad you found it helpful!

Best wishes,

TeachingEnglish team

Research and insight

Browse fascinating case studies, research papers, publications and books by researchers and ELT experts from around the world.

See our publications, research and insight

Jump to navigation

Resources and Programs

- Teaching the Four Skills

- U.S. Culture, Music & Games

- Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs)

- Other Resources

- English Club Texts and Materials

- Teacher's Corner

- Comics for Language Learning

- Online Professional English Network (OPEN)

English language teachers are trained to teach language skills, but they do not always learn how to teach the critical thinking skills that help guide learning. Critical thinking skills are part of many curriculum guidelines, but some teachers may be unsure how to teach these skills. For example, an academic reading curriculum might have the following objective: “Learners will analyze a variety of academic writing samples in an effort to determine the components, organization, and structure of academic writing texts.” Although English language teachers can think of any number of ways to teach and support reading as a skill, they may find it more difficult to achieve the first part of this objective—how to teach learners to analyze.

Critical thinking involves reflection and the analysis of ideas. Good critical thinkers are able to break a broad idea into many parts. They can examine each part, question biases, and come to a reasonable conclusion. This task is difficult for anyone and requires practice. Thinking critically is even more challenging when done in a second language.

This month’s Teacher’s Corner looks at the critical thinking skills that shape learning goals and outcomes. Each week presents a new activity that targets critical thinking skills while also encouraging language use and development. Some of the activities and tasks may seem familiar as they are based on long-established language teaching techniques. The activities are designed to support authentic language use while also encouraging critical thinking.

Brown, H. D. and Lee, H. (2015). Teaching by Principles: An Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy. White Plains, NY: Pearson Longman.

Additional Resources

For additional information about critical thinking , check out the resource below and many others available on the American English website:

· A Questionnaire Project: Integrating the Four Macro Skills with Critical Thinking

Table of Contents

It takes time to design activities and tasks that both target language skills and encourage critical thinking. Project-based learning (also known as experiential learning) is one approach you can use to integrate language-learning goals with critical thinking skills. Project-based learning tasks and activities combine language and action so that learners learn by doing (Brown and Lee, 2015). Learners must understand, examine, analyze, evaluate, and create while using English to complete a task or activity. The result is a language skills task or activity that promotes critical thinking skills.

One of the most popular types of project-based learning in the language classroom is the Language Experience Approach (LEA). LEA gives language learners a chance to recount a personal experience in their own words (Brown and Lee, 2015). This week’s Teacher’s Corner offers an LEA activity that can be conducted in the classroom using minimal resources.

High Beginning

Language Focus

During this activity, students will be able to the following:

- U se English to talk about a special meal they shared with their family.

- Organize th eir experience into a written story.

Paper, pencils

Preparation

- Write the following prompt on the board:

o Describe a special meal you ate with your family.

- When was it?

- What did you eat?

- Where were you?

- Who was with you?

- Have your own story of a special meal ready to share with students.

1. Begin class by telling students: “Today you are going to talk about a special meal you ate with your family.” Direct their attention to the prompt and questions on the board.

2. Ask students to think about a meal. You might say, “Do you remember a special meal with your family? Do you remember two?”

3. Encourage students to begin sharing what they remember. For example, one student might share that they remember a time when they had a family dinner for a birthday or holiday. Use the questions on the board to guide the discussion.

- Keep the conversation moving with different students responding and sharing their memories. The more students talk, the more it will encourage and support other students to remember and share additional details.

- Some student might not be able to think of all of the language required immediately. This is fine. Encourage those students to think about other parts of the meal, and tell them you will come back in a moment.

- Give plenty of time for the discussion so that all students have a clear idea of an occasion that they can write about.

4. Tell students that now they are going to work on writing their story of a special meal.

- Depending on the group, feel free to give them guidelines for writing, but try not to put limitations on what they write. For example, you could say that everyone needs to write at least 5 sentences, but they could write more if they choose.

- Part of LEA is to encourage a learner’s autonomy over their own experience. Allow learners to share their ideas in English without worrying about grammar or spelling. In this way, you can give learners freedom to play with the language, navigate their own story, and negotiate meaning through their language choices.

5. As students write, walk around and support them by helping them write down exactly what they say.

If you have a student who wants to know how to spell something correctly, you can tell them the correct spelling. On the other hand, if a student spells some words incorrectly, do not correct them. Encourage learners to use the English they know and are comfortable using in their stories.

6. After students have written their stories, give everyone a chance to share what they have written.

One way to share the stories is to divide the students into two groups. Have one group hang their stories on the wall and stand next to them. Tell the second group that they are visiting the story gallery, and they can go around the room reading the different stories and asking the authors questions. After students have circulated, the groups can switch tasks. The second group now hosts a story gallery, and the first group gets to read stories and ask questions.

7. Keep all of the stories up on the walls so students can see their work, or encourage students to take their stories home to share with their families.

One variation of this activity is to have learners write their stories in small groups of three or four students. Have one student tell their story out loud while the other students in the group write down the story as they hear it.

An additional variation could involve a whole-class shared experience. Rather than have learners share their individual experiences, you could ask the class to recount an experience you shared as a group. For example, if the class went on a field trip recently, ask the class to recount the field trip together. The teacher becomes the scribe and writes the story on the board, and the students can see their experiences taking shape in writing.

This activity can be extended to include a visual component. Once students have written their stories, ask them to draw a picture depicting the events in the story. This could be done simply with pencil and paper or, if magazines and pictures are available, students could make picture collages to go with their stories.

Reading aloud is a popular reading task in English language classrooms. The task typically targets skills associated with reading, such as fluency, word recognition, and pronunciation. In this week’s Teacher’s Corner, a read-aloud task is used as the framework for a more demanding task that targets critical thinking skills as well. The task asks learners to process and then summarize the content of a story while reading aloud in a group.

Intermediate and above

During this activity, students will be able to complete the following tasks:

- Read a story aloud.

- Consider, evaluate, and plan a summary of a story while reading.

- Present a verbal summary of a story.

Reading: “The Black Cat” by Edgar Allen Poe

- Print enough copies of the story “The Black Cat” by Edgar Allen Poe for each student.

- Place students into groups of 3-4 students before class by creating a list of students in each group.

1. Begin by putting students in the groups planned before class.

2. Tell the class that today they are going to read a story by Edgar Allen Poe called “The Black Cat.”

3. Have each group discuss what they expect the story might be about based on the title and on what they know about Edgar Allen Poe.

4. Ask the class to share what they’ve discussed in groups, and write the ideas on the board. For example, one group might say they know Edgar Allen Poe wrote scary stories so they expect this story to be scary. Another group might say that black cats are believed to be bad luck in some cultures.

5. Give each group a single copy of the story. Tell the class that one student will read three paragraphs aloud to the group. As the person reads, they will stop at the end of each paragraph to summarize the paragraph for the group. After the first student has read and summarized three paragraphs, the next student in the group will read and summarize the next three paragraphs. The group will continue reading the story by taking turns reading aloud and summarizing.

a. If possible, model the activity for students using Appendix A as a sample of reading and summarizing. For example, read the first paragraph in Appendix A aloud to the students. At the end, summarize the paragraph using the suggested summary in Appendix A.

6. Once all of the groups have completed the story, hand out more copies of the story so each student has a copy.

7. Direct students to read the story silently.

8. While students read, write the following questions on the board:

a. What was difficult about reading aloud while summarizing?

b. What part of the activity was easiest?

c. Were your group’s summaries accurate?

9. When everyone has finished reading, ask students to discuss the questions written on the board in their groups.

10. Finally, bring the class back together and ask for some responses to the questions.

Any reading can be used for this activity. The reading should be easy enough for the students to successfully complete the activity, but also difficult enough for them to find the activity challenging.

Another variation might include giving each student a different short text. For example, each student gets a different poem. Students would read aloud and summarize their text, and then the group would evaluate the reader’s performance.

Sample Annotated Read-Aloud

The Tell-Tale Heart

Edgar Allen Poe

It’s true! Yes, I have been ill, very ill. But why do you say that I have lost control of my mind, why do you say that I am mad? Can you not see that I have full control of my mind? Is it not clear that I am not mad? Indeed, the illness only made my mind, my feelings, my senses stronger, more powerful. My sense of hearing especially became more powerful. I could hear sounds I had never heard before. I heard sounds from heaven; and I heard sounds from hell!

Suggested summary:

The person has been sick, but is not crazy. The sickness made the person smarter and improved his hearing. He heard wonderful sounds and horrible sounds.

Making predictions in reading and listening activities is a great way to develop learners’ critical thinking skills. In order to make predictions, learners need to evaluate the components of the information they have while also making reasonable judgments about possible outcomes. Evaluating, reflecting, and making judgments are all part of the critical thinking skills needed for learners to fully engage in learning and to use what they learn beyond the classroom.

In this Teacher’s Corner activity, students use the first part of a comic strip as a starting point for creating their own endings. This activity is simple and fun, and can be used with any age group at any level. As you work through the activity, think about possible variations in addition to those offered below.

Beginning and above

During this activity, students will be able to do the following tasks:

- Read a comic strip and make a reasonable prediction about an ending.

- Plan, write, and draw their own version of the comic strip’s ending.

- Comic strip from American English: Why English? Comics for the Classroom (see Appendix A)

- Comic strip template (see Appendix B)

- Paper, pencils, or any drawing materials available

- Print enough copies of the comic for each student in the class.

1. Begin class by asking students to describe a comic strip.

- Let students offer suggestions, but also ensure that they know comic strips are short stories presented through pictures and words.

2. Write the title of the comic strip on the board, “Lost in the Desert.” Ask learners what they think the comic might be about, based on the title.

3. Tell students that they will read the first part of the comic strip in class and then write new endings.

4. Hand out a copy of the comic strip to each student in the class.

5. Tell learners to look at the pictures and read the language silently.

6. After giving learners time to work individually, read the comic as a group by calling on different students to read aloud.

7. Check learners’ reading comprehension by asking the following questions of the whole class:

- Where is the person in the comic?

- What problem does the person have?

- What does the person try to do to solve the problem?

8. Once the story has been discussed, begin a group brainstorm.

- Ask learners to think about what happens next in the comic strip.

- Encourage students to share some of their ideas with the class.

- Write students’ ideas on the board for everyone to see. Spend at least 5-7 minutes listening and writing their ideas on the board so that students have a chance to hear from their classmates and refine their own ideas.

9. Tell students that it’s now their turn to write and draw the rest of the comic.

- Give them a blank comic strip template (Appendix B) and any additional drawing materials you have available.

- Tell students to use all six squares to complete the story. All six squares must have a drawing. At least three squares must include language.

10. After students have finished their comics, put students into pairs by having students work with the person sitting to their left.

11. In the pairs, students will read the comic with their new endings to their partners.

Instead of having students finish a comic strip, students can make their own comic strips. Then they give the first half of their comic strip to a partner. The partner will then write their own endings to their classmate’s comic strip.

Another alternative is to give students short stories or poems to finish. American English has both poems and short stories available for free to teachers and learners.

Academic writing teachers try to help learners understand and imitate the various rhetorical styles used in academic texts. Understanding academic writing involves careful and repeated reading, analysis, and evaluation of many texts. It then requires further analysis, synthesis, and creation to imitate the writing style. All of this work involves using critical thinking and language skills. One way to engage learners in this process and support the acquisition of advanced writing skills is to use students’ existing critical thinking skills in an activity that analyzes the components of academic writing.

This Teacher’s Corner offers a strategy to introduce learners to academic writing through the familiar task of outlining. Writers use outlining as a way to plan and organize their ideas at the beginning of the writing process. In this activity, learners use the outline in reverse as a way to break down and analyze the structure of an academic text. This process is called a reverse outline and is explained in detail here. Keep in mind that a reverse outline can be adapted to fit the needs of intermediate writers as well, as long as the reading is selected to meet learners’ language level.

Advanced (university level)

- Read an academic text to identify the organization and structure of ideas.

- Organize the information presented in an academic text into an outline template in order to recognize the structure and organization of an academic text.

- Reading: “Helping Students Develop Coherence in Writing” by Icy Lee

- Outline Template in Appendix A

- Paper and pencils or pens

- Print enough copies of the reading for each student.

- Print enough copies of the outline template for each student.

1. Start class with a warm-up discussion to elicit ideas about the structure of academic writing. Use these questions as a guide:

- What are the important parts of an academic essay?

- What do we call the first paragraph(s)? The main paragraphs? The final paragraph(s)?

- What have you been told to include in the first paragraph(s) of an essay?

- What is included in the main paragraphs?

- What is included in the final paragraph(s)?

2. Hand out the outline template (Appendix A) to students. (The outline template can be adapted and adjusted to meet the needs of essay writing in your specific class. Feel free to add components to this outline or delete components that are unnecessary.) Ask learners to review the template for similarities between what they said in the discussion and what the template lists as components of academic writing.

- Is there anything on the outline template that was not mentioned in the discussion? If so, what are the differences? Is there anything that students think the outline template needs to include that is not listed?

3. Explain that this outline is a model of the structure, but that every article differs slightly as to how each of the core parts is structured. For example, one essay might have 10 body paragraphs but another essay might only have 4.

4. Tell students they are now going to use the outline to read an academic article. They will complete an outline, using the template as a model, based on the information from the article they read.

5. Give everyone a copy of the article. Explain that before trying to complete the outline, they should read the article once and make notes. Reading once will help them process the article, ask questions, and get an overview of the structure of the article.

6. Have learners read, make notes, and complete their outlines. While they are working, circulate to answer any questions they have.

7. After learners have completed the outlines, bring the class back together as a group.

8. Place students in pairs by dividing the class in half and counting off each group (for example: 1, 2, 3, 4, etc.). The two students who are assigned 1 will work together, the students assigned 2 will work together, etc.

9. Once learners are in their pairs, ask them to read over their partners’ outlines, paying attention to similarities and differences.

10. While they are reading, write these directions on the board.

- Compare the two outlines and identify any areas where the information is different or where information is on one outline but not the other.

- Work together to complete a new outline that combines the information from both outlines.

- Work together to decide how to include information that is different on personal outlines.

11. Then give each pair a new outline template. Explain that students will work together to create a new outline, using the directions on the board.

12. When pairs have finished, bring the class back together to discuss what they learned from the outline activity.

- What information on the outline did they expect to see? What information was unexpected in the article’s structure? What else did they learn about how academic writing is structured?

One simple variation is to have students read the text at home and take notes before working on the outline in class. This variation allows students to read at their own pace so that when students come to class, they are all familiar with the text.

Another alternative to this assignment is to have students work in pairs from the beginning of the process. After everyone in the class reads the article, put students in pairs and have them work together to complete the outlines. This variation ensures that learners will vocalize, discuss, and negotiate what is included on the outline and what is not.

A possible extension to this activity is to revisit the reverse outline when students are writing their own essays. During the revision process students could complete a reverse outline of their own work or complete reverse outlines of their classmates’ work. For example, if students have written a first draft of an essay, before they revise it or write a second draft, they could do a reverse outline of their first draft. By doing so, they could recognize areas in their writing to improve. Then, students could use their reverse outline for help in preparing and writing a second draft.

Outline Template

I. Introduction

- Attention grabbing device

- Background/Contextual information

- Thesis statement

II. Main Paragraphs (repeat for each paragraph)

- Topic statements/ideas

- Supporting evidence (data, anecdotes, stories, definitions, etc.): paraphrase, summary, quotes

- Connections to thesis

III. Conclusion

- Final thoughts

- Implications and areas for future analysis

- Suggestions for next steps

- Privacy Notice

- Copyright Info

- Accessibility Statement

- Get Adobe Reader

For English Language Teachers Around the World

The Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, U.S. Department of State, manages this site. External links to other Internet sites should not be construed as an endorsement of the views or privacy policies contained therein.

Critical Thinking and English Language Teaching Pt. 1

- By Anthony Schmidt

Critical Thinking And English Language Teaching Pt. 1

Critical thinking has been a buzzword for some time now. In fact, judging by the research, it has been a buzzword for over a decade. The problem with buzz words is that, over time, they lose a lot of their original meaning and begin to stand for almost anything new or progressive. In addition, it has become an empty rallying cry (“We must teach critical thinking in English language teaching!”) devoid of the very thinking it purports to support .

Why does hearing the cry above make people cringe? Why does reference to Bloom’s taxonomy often cause negative reactions? One reason is because these terms are overused. But is there something more? Are people (rightly) skeptical of these concepts?

There is no doubt that “critical thinking” is buzzworthy. And, if it’s buzzworthy, it must have some importance. So, what exactly is critical thinking and why is it important? I believe the answer to these questions can be framed through the arguments of those who are critical of critical thinking. This article will briefly consider the research on critical thinking and argue that critical thinking should play a central and explicit role in English language teaching.

Can Critical Thinking Be Defined?

There are those who feel that critical thinking can only be defined in broad, subjective terms that are too various to unify. How do you teach something if you can’t even define it? The literature on critical thinking – coming from psychology, education, and philosophy, agrees somewhat with this point. It seems that critical thinking is not readily reducible. It is, rather, multidimensional, or, polysemous. Nevertheless, while the idea of critical thinking may be expressed in various ways, Moore found that these are typically well-articulated and clearly conveyed to students. Moore claims that the variety of meanings may be discipline-based, meaning that psychology prefers certain aspects of critical thinking more so than history, which prefers others. Still, Moore was able to identify some common features which can define the concept more clearly.

According to Moore’s research, critical thinking is:

- A judgement of whether something is good, bad, valid, or true

- rational, or, reason-based

- skeptical thinking

- productive thinking – not only challenging ideas but producing them – coming to conclusions about issues

- carefully reading beyond a text’s literal meaning

- awareness of the entire process

- ethical or activist – in other words, not neutral

Although Moore is not the sole and final authority on what is means to be a critical thinker, it’s clear that critical thinking can be somewhat defined as a concept, though we must accept that its meaning – like many other concepts – “is its use in the language” (Wittgenstein, cited in Moore, p. 508).

Can Critical Thinking Be Taught?

If critical thinking can be defined (as Moore and others have done), then can it be taught? Certainly, it’s important to think critically. No one is arguing it is not. However, many claim that it must be organically developed, or it is a skill that can be encouraged but not learned. The literature, however, shows the opposite. Not only can critical thinking be taught, it can be practiced and refined!

First, we have to understand that critical thinking is hard. Experimental research by Kuhn (1991) shows that a majority of people cannot demonstrate critical reasoning skills. That is, they cannot often justify their beliefs and opinions with evidence.

Van Gelder and Mulnix, mulling over the question of how to teach critical thinking, found some practical advice, much of which is based in cognitive science.

- Examples of critical thinking are not enough – students need to engage in critical thinking.

- There needs to be deliberate practice to master the skill. This includes full concentration, exercises aimed at improving the skills, engaging in increasingly difficult exercises as easier ones are mastered, and guidance and feedback.

- The practice must be repetitive throughout a course.

- Students must practice transferring critical thinking skills to other contexts.

- Students must eventually become aware of the actual idea of critical thinking, including its terminology.

Empirical research on critical thinking shows that it not only can be taught but must be taught. As teachers, we should develop exercises, strategies, and assessments that seek to improve this skill. Mulnix concludes rather poignantly, “To do any less is not only to let our students down, but it is to fail at that very skill we are trying to teach”.

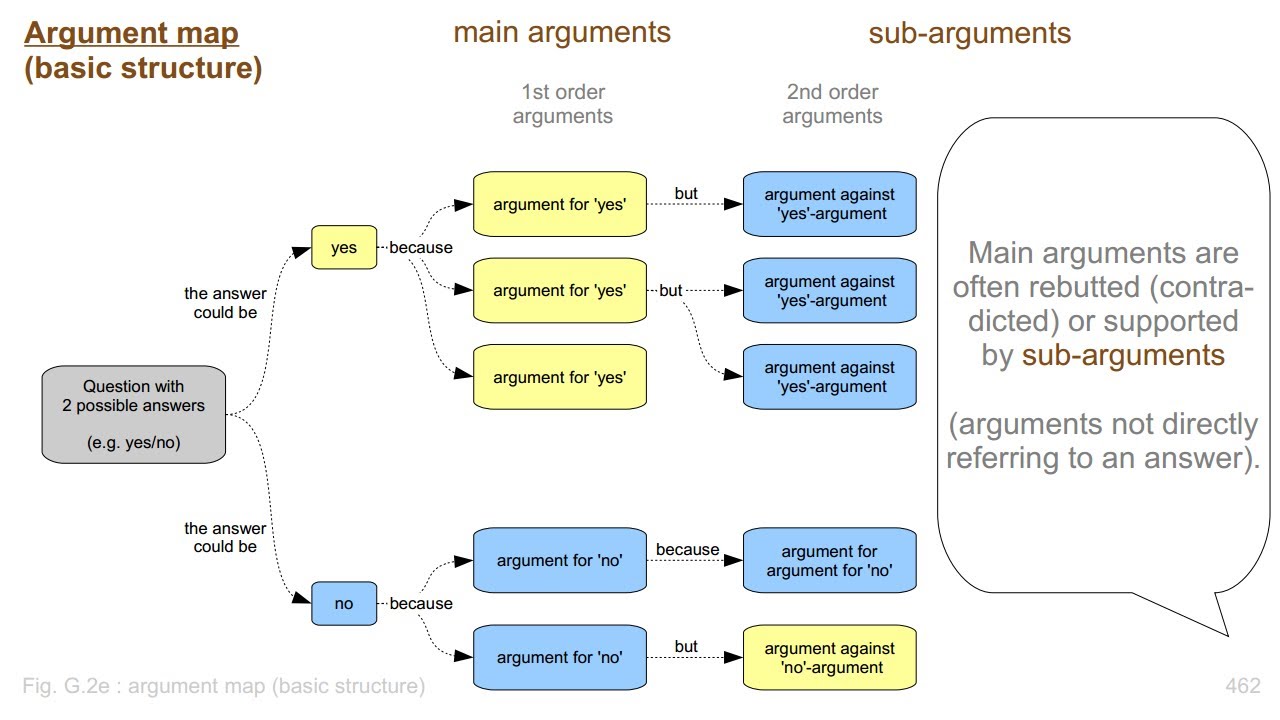

One exercise that has been shown to be effective is argument mapping, in which arguments (including claims, warrants, evidence, etc.) are visually displayed in a diagram. This makes it easy to understand, analyze, and evaluate arguments. Argument maps start with a central premise (i.e. thesis) at the top and include below it evidence or reasons, co-premises (co-reasons), counterarguments and rebuttals, with lines and arrows to show the connections between the ideas.

As a classroom activity, argument maps can first be given as templates that students fill in. Once familiar with argument mapping, they can then begin to construct their own based on analyzing textual sources (readings or lectures) or for forming their own logical conclusions (for discussions, debates, and presentations). By analyzing the arguments written, students can then begin evaluating reasons, evidence, and counterarguments. They can begin questioning the validity of these arguments and suggest their own conclusions or justification. In this way, they are deliberately engaging in critical thinking practice, which, as shown above, is key for developing good critical thinking skills.

Argument map examples:

Wait! What About Bloom’s Taxonomy?

Bloom’s taxonomy is perhaps the most well-known example of critical thinking. It is an orderly, visually-pleasing representation of, as we have seen, quite a large concept – and this is perhaps one reason why it has held educational weight since the late 50s. However, it has come under much scrutiny both for the way it has been organized and the way it has been employed. There is poor empirical basis for the organization of the hierarchy and its implications for task sequencing. “Lower order skills” are not necessarily easier than “higher order skills” and vice-versa. In addition, these “lower” skills are often used in conjunction or even after using the “higher order skills”.

Nevertheless, Bloom’s (revised) taxonomy is still quite common in the scientific literature. A search for “bloom’s taxonomy” on Google Scholar reveals a great deal of peer-reviewed research which utilized Bloom’s taxonomy. So, why the persistence? While the hierarchy may have its weaknesses and its organization may not always represent reality, the levels of the taxonomy do include most conceptions of what critical thinking is, and there is evidence from neuroscience that supports the taxonomy itself. In the video, “ What can Neuroscience Research Teach Us about Teaching? ”, neuroscientist Daniel Kaufer points to Bloom’s taxonomy as an example of active learning in which, as one moves up the hierarchy, more and more areas of the brain become dynamically activated. In other words, when more areas of the brain “fire together” they typically “wire together” . So, working on higher order skills may not be more difficult than lower order skills, but it may lead to stronger reinforcement of learning.

One of the alternatives to the taxonomy Case proposes is very much aligned with what we have read above about the pedagogical ideas behind teaching critical thinking:

“Understand that inviting students to offer reasoned judgments is a more fruitful way of framing learning tasks than is the use of verbs clustered around levels of thinking that are removed from evaluative judgments”. [jbox title=”Reference List”]

Atkinson, D. (1997). A critical approach to critical thinking in TESOL. TESOL quarterly , 31 (1), 71-94.

Case, R. (2013). The Unfortuate Consequences of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Social Education , 77 (4), 196-200.

Dalton, D. F. (2011, December). An investigation of an approach to teaching critical reading to native Arabic-speaking students. Arab World English Journal, 2 (4),58-87.

Davidson, B. W. (1998). Comments on Dwight Atkinson’s” A Critical Approach to Critical Thinking in TESOL”: A case for critical thinking in the English language classroom. TESOL quarterly , 32 (1), 119-123.

Hernandez, M. L., & Rodríguez, L. F. G. (2015). Transactional Reading in EFL Learning: A Path to Promote Critical Thinking through Urban Legends. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal , 17 (2), 229-245.

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains: Disposition, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. American Psychologist , 53 (4).

Moore, T. (2013). Critical thinking: seven definitions in search of a concept. Studies in Higher Education , 38 (4), 506-522.

Mulnix, J. W. (2012). Thinking critically about critical thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory , 44 (5), 464-479.

Nezami, S. R. A. (2012). A critical study of comprehension strategies and general problems in reading faced by Arab EFL learners with special reference to Najran University in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Social Sciences and Education, 2 (3), 306-317.

Parrish, B., & Johnson, K. (2010, April). Promoting learner transitions to post-secondary education and work: Developing academic readiness from the beginning. CAELA

Network Briefs. Retrieved June 1, 2015 from http://www.cal.org/caelanetwork/resources/transitions.html

Ramanathan, V., & Kaplan, R. B. (1996). Some problematic” channels” in the teaching of critical thinking in current LI composition textbooks: Implications for L2 student-writers. Issues in Applied Linguistics , 7 (2).

van Gelder, T. (2005). Teaching critical thinking: Some lessons from cognitive science. College teaching , 53 (1), 41-48.

Wong, B. L. (2016). Using Critical-Thinking Strategies To Develop Academic Reading Skills Among Saudi Iep Students.

Related Topics

- Critical Thinking

- English language

- Neuroscience

- Presentations

Anthony Schmidt

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

6 Responses

Thanks for this really well researched and written article, Anthony. I particularly liked your suggestion of 'argument mapping'. I think it could be a great way for students to plan their academic assignments. I'd like to discuss some possible computer tools which may be useful for students to use when argument mapping. One could be the Microsoft Word SmartArt function. Another could be this mindmapping website: I'd love to hear about any other suggestions. Sam

Thanks Sam. I think argument mapping has a lot of uses, and it is a technique that has not been utilized much in ELT. This is likely because few of us have little experience or knowledge of it. Thanks for sharing the mindmap website. It's really cool and I can see a lot of uses well beyond argument maps. Vocabulary lists were the first thing to pop into my mind. Again, really cool! Thanks again.

Karl Millsom

Eagerly awaiting part 2. Indeed, buzzwords pick up debris as they popularise, and too often eventually they get cast out entirely, the core and sound principles included. This article does a good job of extracting the baby from the bathwater. The argument mapping is something I use a lot here in Indonesia when teaching how to write essays to post graduates who have often not encountered the concept of structured academic writing at all in all their years of schooling. Your examples are very well presented.

Thank you for sharing this primer defining, questioning, and contextualizing "critical thinking" in ELT. While many English majors usually choose the essay as the place to teach argument and critical thinking, our EFL and ESL classrooms provide many other opportunities too. Argument mapping is an excellent, flexible technique. In teaching adult education, community college, university, and graduate students, it's also often helpful to deploy problem-solution assignments to develop critical thinking. It can be personal challenge and crucial life skill (staying healthy, choosing a major) or a common social problem (affordable housing, reducing pollution). You can also scale up the vocabulary to fit the situation with risks/benefits, trade offs, and stakeholders. Likewise, asking students to write consumer reviews often works. Consumer reviews provide students with a chance to present facts, express opinions, and provide supporting evidence. Students can also share movie reviews, product reviews, and restaurant reviews online with authentic English-speaking audiences. I've found many ESL and EFL students far more receptive to critical teacher feedback when they plan to share their consumers with the "public" at large, and rewrite class assignments to reach higher standards. Amazon, Yelp, and other review sites have opened up exceptional possibilities and new audiences for student writing. Unfortunately, as the declining level of political discourse in several elections around the democratic world show, critical thinking remains in short supply. Sometimes a powerful slogan - Make America Great Again - can seduce many voters. Would it be helpful for the word "great" to be defined? Would it be useful to know, in some detail, what proposals were being advocated to reach that objective? How will the proposal be implemented? What are the probable costs? What are the likely benefits? What's the timeline? Critical thinking at some level asks students to go from vague generalizations to accurate, detailed suggestions. Numbers add precision. Sources provide credibility. Example illuminate. From my perspective, teaching critical thinking also often requires teaching students to go from the language of false certainty to possibility and probability. Deploying frequency adverbs and hedging language often helps. Thank you, again, for sharing your experiences and research with EFL Magazine readers.

Thanks for the reply Eric. You raise many interesting points, all of which I agree with. I find that finding ways of making the audience authentic - not an easy task - paired with critical thinking makes for excellent assignments and student practice. I really like what you said here: " Numbers add precision. Sources provide credibility. Example illuminate." It's a good way to put it and can easily be explained to students in this manner.

I'm finding argument mapping to be more and more useful. I have not actually used it for outlining but have used it for breaking down readings, and using the information in the map to inform new writings.

Related Articles

Teaching English One to One – Creating Comfort

The growth mindset and language learning.

Empathy – We Must Learn to Speak This Language of Connection

Five Techniques to Merge Storytelling and Mindfulness

Privacy overview.

- ELT News Get the latest ELT news! Our international network of journalists are always on the hunt for the latest and greatest news in the English language teaching space around the globe, so you can stay informed. Hear about breaking industry topics, international trends and issues, and other news relevant to you and your career.

- Teaching English Online Online English teaching is the fastest-growing sector in English language teaching. Whether you’re new to teaching and want to find out more or are an established online tutor looking for professional development, advice, or practical classroom activities, we have resources for all types of virtual EFL teachers. Learn about the skills and technology needed for the virtual classroom, online teaching salaries, job opportunities, best practices, and much more. We’ll help you successfully navigate teaching English online from home!

- Classroom Activities Incorporate interactive ESL/EFL games and activities into your lesson plans to keep your students engaged and learning. Discover the most reliable methods for injecting fun and excitement into your online or in-person classroom whether your students are young learners, teens, or business professionals. These TESOL games and activities range from icebreakers that give EFL students conversation practice to knowledge-based games that test students’ understanding of concepts.

- Pedagogy Learn about the latest pedagogy for TEFL/TESOL from the experts. Stay up to date with new teaching trends and learn how to be the most effective English teacher you can be. We’ll show you how to incorporate 21st-century skills into your classes, teach you to effectively use ESL games and activities to engage your students, and offer insights into ESL teaching methods like code-switching. ELT pedagogy is constantly evolving, so ensure you have the latest information to succeed in your teaching goals.

- Technology in English Language Teaching Stay ahead in English language teaching with the latest tech tools and trends. From language learning apps to AI-driven resources, explore ways to integrate technology that enhances student engagement, personalizes learning, and simplifies lesson planning. Discover articles on everything from virtual classrooms and interactive platforms to data-driven assessments, all geared toward helping you make the most of digital tools in your ESL/EFL teaching practice.

- Professional Development Take your teaching career to the next level with professional development. Whether it’s earning a Specialized TEFL/TESOL certificate to enhance your resume, taking a Micro-credential course to learn a new skill you can use to improve your teaching, or watching ELT webinars on hot industry topics, we’re always offering new professional development opportunities to our global teachers.

- Teaching English Independently Gain insights into the world of independent English teaching. Whether you’re launching your own tutoring business as a teacherpreneur, freelancing for a company, or teaching through an ELT marketplace, get advice on choosing a niche, creating a strong teacher profile, and more. From building a student base to setting rates and creating resources, these articles provide essential tips for teaching English on your own terms.

- Job Resources Ready to land the English teaching job of your dreams? Get tips on how stand out in a competitive market, design a professional TEFL/TESOL resume and cover letter, ace your TEFL job interview, and more. Plus, learn how to take advantage of Bridge’s wide range of job resources and services, including our network of Preferred Employment Partners and digital badges, dynamic credentials that showcase your skills to potential employers.

- TEFL Certification Explore everything you need to know about TEFL certification, from choosing the right program to understanding course components. Learn how a TEFL certificate can expand your career options, open doors to international teaching, and enhance your teaching skills. We offer guidance for both new teachers and experienced educators looking to deepen their qualifications in the ever-evolving TEFL field.

- Teaching English Abroad Whether you’re new to teaching or looking to make a change, we have resources to help you start your journey teaching English abroad off on the right foot or take the next step in your career. With the right tools, you can teach English online while traveling as a digital nomad or teach abroad in a traditional school setting. Learn how to be a better teacher for your international students, land the teach abroad job of your dreams, and make the transition to life abroad. We’re here to help every step of the way, from TEFL/TESOL certification that will qualify you for jobs around the world to vetting TEFL employers, so you can find a legitimate job while traveling or living in a foreign country. Embrace the adventure. We’ll help with the rest!

- Teaching English Proficiency Test Preparation Prepare students for success on English proficiency exams with strategies and insights for test prep. Whether teaching preparation for the IELTS, TOEFL, PTE, or other exams, discover best practices for each test section, ways to boost student confidence, and resources to structure effective study sessions. From scoring tips to test-taking strategies, these articles cover all aspects of guiding learners to achieve their desired scores.

FOR EDUCATORS

- Teaching Business English

For HR Teams

- Corporate Language Training

- Corporate Language Case Study Interviews

FOR LEARNERS

- Study Resources and Tips

- SEE ALL TOPICS Empower learners and organizations to communicate effectively in today’s global marketplace with our Business English insights and resources. These articles cover everything from teaching strategies and curriculum design to specialized training for corporate environments. Whether you’re an educator, HR professional, or learner, find essential tools and tips to enhance English skills for the workplace, from practical language applications to cultural nuances in business communication.

- Corporate Language Programs

- TEFL Events

- Expert Series Webinars

- Promote Your Own ELT Event!

- Company News Stay up to date with the latest happenings at Bridge! From new partnerships and program launches to milestones and industry events, stay informed about what’s new and exciting in our organization. Dive into articles on how we’re growing, innovating, and contributing to the English language teaching industry to better serve educators, learners, and corporate clients worldwide.

- Meet the Team Meet the Bridge Team! Our advisors, course tutors, and staff share their backgrounds, TEFL/TESOL stories, and best tips so you can get to know our international team and learn more about our experience in the industry. We’re here to help you every step of your TEFL journey, so get to know us a little better!

- Alumni Stories Hear from Bridge students and grads all over the globe who are fulfilling their TEFL/TESOL goals by teaching English abroad, online, and in their home countries. Find out what a day in the life is like for these English teachers, how their Bridge course has helped them achieve their teaching goals, and what their future teaching plans are. Bridge voices can be found all over the world – hear their stories today!

Explore More

Stay in our orbit.

Stay connected with industry news, resources for English teachers and job seekers, ELT events, and more.

Explore Topics

- Teaching English Online

- Classroom Activities

- Technology in English Language Teaching

- Professional Development

- Teaching English Independently

- Job Resources

- TEFL Certification

- Teaching English Abroad

- Teaching English Proficiency Test Preparation

- Bridge News

Popular Articles

- What Is TESOL? What Is TEFL? Which Certificate Is Better – TEFL or TESOL?

- 5 Popular ESL Teaching Methods Every Teacher Should Know

- 10 Fun Ways to Use Realia in Your ESL Classroom

- How to Teach ESL Vocabulary: Top Methods for Introducing New Words

- Advice From an Expert: TEFL Interview Questions & How to Answer Them

Teaching Critical Thinking Skills in the ESL Classroom

- Linda D'Argenio

- December 22, 2022

Critical thinking has become a central concept in today’s educational landscape, regardless of the subject taught. Critical thinking is not a new idea. It has been present since the time of Greek philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Socrates’ famous quote, “Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel,” underscores the nature of learning (students are not blank slates to be filled with content by their teachers) and the significance of inquisitiveness in a true learning process, both in the ESL classroom and in the wider world of education. Teaching critical thinking skills in the ESL classroom will benefit your students throughout their language-learning journey.

In more recent times, philosopher John Dewey made critical thinking one of the cornerstones of his educational philosophy. Nowadays, educators often quote critical thinking as the most important tool to sort out the barrage of information students are exposed to in our media-dominated world , to analyze situations and elaborate solutions. Teaching critical thinking skills is an integral part of teaching 21st-century skills .

Table of Contents

What is critical thinking?

There are many definitions of critical thinking. They are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary. Some of the main ones are outlined below.

Dewey’s definition

In John Dewey’s educational theory, critical thinking examines the beliefs and preexisting knowledge that individuals use to assess situations and make decisions. If such beliefs and knowledge are faulty or unsupported, they will lead to faulty assessments and decision-making. In essence, Dewey advocated for a scientific mindset in approaching problem-solving .

Goal-directed thinking

Critical thinking is goal-directed. We question the underlying premises of our reflection process to ensure we arrive at the proper conclusions and decisions.

Critical thinking as a metacognitive process

According to Matthew Lipman, in Thinking in Education, “Reflective thinking is thinking that is aware of its own assumptions and implications as well as being conscious of the reasons and evidence that support this or that conclusion. (…) Reflective thinking is prepared to recognize the factors that make for bias, prejudice, and self-deception . It involves thinking about its procedures at the same time as it involves thinking about its subject matter” (Lipman, 2003).

Awareness of context

This is an important aspect of critical thinking. As stated by Diane Halpern in Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinking , “[The critical] thinker is using skills that are thoughtful and effective for the particular context and type of thinking task” (Halpern, 1996)

What are the elements of critical thinking?

Several elements go into the process of critical thinking.

- Identifying the problem. If critical thinking is viewed mainly as a goal-oriented activity, the first element is to identify the issue or problem one wants to solve. However, the critical thinking process can be triggered simply by observation of a phenomenon that attracts our attention and warrants an explanation.

- Researching and gathering of information that is relevant to the object of inquiry. One should gather diverse information and examine contrasting points of view to achieve comprehensive knowledge on the given topic.

- Evaluation of biases. What biases can we identify in the information that has been gathered in the research phase? But also, what biases do we, as learners, bring to the information-gathering process?

- Inference. What conclusions can be derived by an examination of the information? Can we use our preexisting knowledge to help us draw conclusions?

- Assessment of contrasting arguments on an issue. One looks at a wide range of opinions and evaluates their merits.

- Decision-making. Decisions should be based on the above.

Why is critical thinking important in ESL teaching?

The teaching of critical thinking skills plays a pivotal role in language instruction. Consider the following:

Language is the primary vehicle for the expression of thought, and how we organize our thoughts is closely connected with the structure of our native language. Thus, critical thinking begins with reflecting on language. To help students understand how to effectively structure and express their thinking processes in English, ESL teachers need to incorporate critical thinking in English Language Teaching (ELT) in an inclusive and interesting way .

For ESL students to reach their personal, academic, or career goals, they need to become proficient in English and be able to think critically about issues that are important to them. Acquiring literacy in English goes hand in hand with developing the thinking skills necessary for students to progress in their personal and professional lives. Thus, teachers need to prioritize the teaching of critical thinking skills.

How do ESL students develop critical thinking skills?

Establishing an effective environment

The first step in assisting the development of critical thinking in language learning is to provide an environment in which students feel supported and willing to take risks. To express one’s thoughts in another language can be a considerable source of anxiety. Students often feel exposed and judged if they are not yet able to communicate effectively in English. Thus, the teacher should strive to minimize the “affective filter.” This concept, first introduced by Stephen Krashen, posits that students’ learning outcomes are strongly influenced by their state of mind. Students who feel nervous or anxious will be less open to learning. They will also be less willing to take the risks involved in actively participating in class activities for fear that this may expose their weaknesses.

One way to create such an environment and facilitate students’ expression is to scaffold language so students can concentrate more on the message/content and less on grammar/accuracy.

Applying context

As mentioned above, an important aspect of critical thinking is context. The information doesn’t exist in a vacuum but is always received and interpreted in a specific situational and cultural environment. Because English learners (ELs) come from diverse cultural and language backgrounds and don’t necessarily share the same background as their classmates and teacher, it is crucial for the teacher to provide a context for the information transmitted. Contextualization helps students to understand the message properly.

Asking questions

One of the best ways to stimulate critical thinking is to ask questions. According to Benjamin Bloom’s taxonomy ( Taxonomy of Educational Objectives , 1956), thinking skills are divided into lower-order and higher-order skills. Lower-order skills include knowledge, comprehension, and application; higher-order skills include analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. To stimulate critical thinking in ELT, teachers need to ask questions that address both levels of thinking processes. For additional information, read this article by the TESL Association of Ontario on developing critical thinking skills in the ESL classroom .

Watch the following clip from a BridgeUniverse Expert Series webinar to learn how to set measurable objectives based on Bloom’s Taxonomy ( watch the full webinar – and others! – here ):

How can we implement critical thinking skills in the ESL classroom?

Several activities can be used in the ESL classroom to foster critical thinking skills. Teaching critical thinking examples include:

Activities that scaffold language and facilitate students’ expression

These can be as basic as posting lists of important English function words like conjunctions, personal and demonstrative pronouns, question words, etc., in the classroom. Students can refer to these tables when they need help to express their thoughts in a less simplistic way or make explicit the logical relation between sentences (because… therefore; if… then; although… however, etc.). There are a variety of methods to introduce new vocabulary based on student age, proficiency level, and classroom experience.

Activities that encourage students to make connections between their preexisting knowledge of an issue and the new information presented

One such exercise consists of asking students to make predictions about what will happen in a story, a video, or any other context. Predictions activate the students’ preexisting knowledge and encourage them to link it with the new data, make inferences, and build hypotheses.

Critical thinking is only one of the 21st-century skills English students need to succeed. Explore all of Bridge’s 21st-Century Teaching Skills Micro-credential courses to modernize your classroom!

Change of perspective and contextualization activities.

Asking students to put themselves in someone else’s shoes is a challenging but fruitful practice that encourages them to understand and empathize with other perspectives. It creates a different cultural and emotional context or vantage point from which to consider an issue. It helps assess the merit of contrasting arguments and reach a more balanced conclusion.

One way of accomplishing this is to use a written text and ask students to rewrite it from another person’s perspective. This automatically leads students to adopt a different point of view and reflect on the context of the communication. Another is to use roleplay . This is possibly an even more effective activity. In role-play, actors tend to identify more intimately with their characters than in a written piece. There are other elements that go into acting, like body language, voice inflection, etc., and they all need to reflect the perspective of the other.

Collaborative activities

Activities that require students to collaborate also allow them to share and contrast their opinions with their peers and cooperate in problem-solving (which, after all, is one of the goals of critical thinking). Think/write-pair-share is one such activity. Students are asked to work out a problem by themselves and then share their conclusions with their peers. A collaborative approach to learning engages a variety of language skill sets, including conversational skills, problem-solving, and conflict resolution, as well as critical thinking.

In today’s educational and societal context, critical thinking has become an important tool for sorting out information, making decisions, and solving problems. Critical thinking in language learning and the ESL classroom helps students to structure and express their thoughts effectively. It is an essential skill to ensure students’ personal and professional success.

Take an in-depth look at incorporating critical thinking skills into the ESL classroom with the Bridge Micro-credential course in Promoting Critical Thinking Skills.

Linda D'Argenio

Linda D'Argenio is a native of Naples, Italy. She is a world language teacher (English, Italian, and Mandarin Chinese,) translator, and writer. She has studied and worked in Italy, Germany, China, and the U.S. In 2003, Linda earned her doctoral degree in Classical Chinese Literature from Columbia University. She has taught students at both the school and college levels. Linda lives in Brooklyn, NY.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

For more on critical thinking, read How you can encourage critical thinking in the era of 'fake news'. Get teaching tips, insights, and resources straight to your inbox when you create your free World of Better Learning account today. Reference. Tara DeLecce. 2018. What is Critical Thinking? - Definition, Skills & Meaning.

Series 3, episode 7: What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into English language teaching? This week, Chris and We'am discuss critical thinking - what does it mean, why is it important and what role does it have to play in English language teaching? Chris and We'am start by talking about critical thinking as a mindset rather than as a skill separate to other learning. First ...

This article critically reviews 23 empirical studies on how to teach critical thinking (CT) in English as a foreign language (EFL) writing class from 2013 to 2022. ... The tesol encyclopedia of english language teaching, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York (2018), pp. 1-6. Crossref Google Scholar. Gnadimathi and Zarei, 2018.

English language teachers are trained to teach language skills, but they do not always learn how to teach the critical thinking skills that help guide learning. Critical thinking skills are part of many curriculum guidelines, but some teachers may be unsure how to teach these skills. For example, an academic reading curriculum might have the ...

Critical Thinking may seem like a tough topic to tackle, but most of the time we are analysing our every decision without even realising it! In this blog post, we discuss some aspects of Critical Thinking you can teach in your class. There are also three lesson plans for you to try. Critical thinking is a key skill needed for everyday life.

Critical Thinking And English Language Teaching Pt. 1. Critical thinking has been a buzzword for some time now. In fact, judging by the research, it has been a buzzword for over a decade. The problem with buzz words is that, over time, they lose a lot of their original meaning and begin to stand for almost anything new or progressive.

ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING Harits Masduqi ([email protected]) The University of Sydney New South Wales 2006, Australia Universitas Negeri Malang Jl. Semarang 05 Malang 65145, Indonesia Abstract: Many ELT experts believe that the inclusion of critical thinking skills in English classes is necessary to improve students' English compe-tence.

Teaching critical thinking skills is an integral part of teaching 21st-century skills. Applying critical thinking skills to media is a lifelong skill. ... ESL teachers need to incorporate critical thinking in English Language Teaching (ELT) in an inclusive and interesting way.

This book focuses on the role of critical thinking in the English language classroom, showing how it can be used to achieve a greater understanding of individual words and sentences, of longer pieces of discourse, of ideas, and of ... Others say that the absence of an established definition "acts as a barrier" to teaching critical thinking ...

In English as first language contexts, clear requirement for critical thinking (CT) has been listed in teaching guidelines and assessment criteria in higher education.