Can Money Really Buy Happiness?

Money and happiness are related—but not in the way you think..

Updated November 10, 2023 | Reviewed by Chloe Williams

- More money is linked to increased happiness, some research shows.

- People who won the lottery have greater life satisfaction, even years later.

- Wealth is not associated with happiness globally; non-material things are more likely to predict wellbeing.

- Money, in and of itself, cannot buy happiness, but it can provide a means to the things we value in life.

Money is a big part of our lives, our identities, and perhaps our well-being. Sometimes, it can feel like your happiness hinges on how much cash is in your bank account. Have you ever thought to yourself, “If only I could increase my salary by 12 percent, I’d feel better”? How about, “I wish I had an inheritance. How easier life would be!” I don’t blame you — I’ve had the same thoughts many times.

But what does psychological research say about the age-old question: Can money really buy happiness? Let’s take a brutally honest exploration of how money and happiness are (and aren’t) related. (Spoiler alert: I’ve got bad news, good news, and lots of caveats.)

Higher earners are generally happier

Over 10 years ago, a study based on Gallup Poll data on 1,000 people made a big headline in the news. It found that people with higher incomes report being happier... but only up to an annual income of $75,000 (equivalent to about $90,000 today). After this point, a high emotional well-being wasn’t directly correlated to more money. This seemed to show that once a persons’ basic (and some “advanced”) needs are comfortably met, more money isn’t necessary for well-being.

But a new 2021 study of over one million participants found that there’s no such thing as an inflection point where more money doesn’t equal more happiness, at least not up to an annual salary of $500,000. In this study, participants’ well-being was measured in more detail. Instead of being asked to remember how well they felt in the past week, month, or year, they were asked how they felt right now in the moment. And based on this real-time assessment, very high earners were feeling great.

Similarly, a Swedish study on lottery winners found that even after years, people who won the lottery had greater life satisfaction, mental health, and were more prepared to face misfortune like divorce , illness, and being alone than regular folks who didn’t win the lottery. It’s almost as if having a pile of money made those things less difficult to cope with for the winners.

Evaluative vs. experienced well-being

At this point, it's important to suss out what researchers actually mean by "happiness." There are two major types of well-being psychologists measure: evaluative and experienced. Evaluative well-being refers to your answer to, “How do you think your life is going?” It’s what you think about your life. Experienced well-being, however, is your answer to, “What emotions are you feeling from day to day, and in what proportions?” It is your actual experience of positive and negative emotions.

In both of these studies — the one that found the happiness curve to flatten after $75,000 and the one that didn't — the researchers were focusing on experienced well-being. That means there's a disagreement in the research about whether day-to-day experiences of positive emotions really increase with higher and higher incomes, without limit. Which study is more accurate? Well, the 2021 study surveyed many more people, so it has the advantage of being more representative. However, there is a big caveat...

Material wealth is not associated with happiness everywhere in the world

If you’re not a very high earner, you may be feeling a bit irritated right now. How unfair that the rest of us can’t even comfort ourselves with the idea that millionaires must be sad in their giant mansions!

But not so fast.

Yes, in the large million-person study, experienced well-being (aka, happiness) did continually increase with higher income. But this study only included people in the United States. It wouldn't be a stretch to say that our culture is quite materialistic, more so than other countries, and income level plays a huge role in our lifestyle.

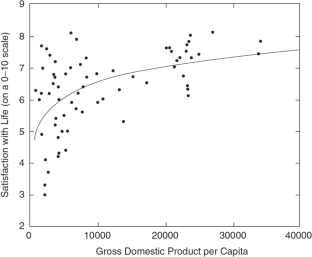

Another study of Mayan people in a poor, rural region of Yucatan, Mexico, did not find the level of wealth to be related to happiness, which the participants had high levels of overall. Separately, a Gallup World Poll study of people from many countries and cultures also found that, although higher income was associated with higher life evaluation, it was non-material things that predicted experienced well-being (e.g., learning, autonomy, respect, social support).

Earned wealth generates more happiness than inherited wealth

More good news: For those of us with really big dreams of “making it” and striking it rich through talent and hard work, know that the actual process of reaching your dream will not only bring you cash but also happiness. A study of ultra-rich millionaires (net worth of at least $8,000,000) found that those who earned their wealth through work and effort got more of a happiness boost from their money than those who inherited it. So keep dreaming big and reaching for your entrepreneurial goals … as long as you’re not sacrificing your actual well-being in the pursuit.

There are different types of happiness, and wealth is better for some than others

We’ve been talking about “happiness” as if it’s one big thing. But happiness actually has many different components and flavors. Think about all the positive emotions you’ve felt — can we break them down into more specifics? How about:

- Contentment

- Gratefulness

...and that's just a short list.

It turns out that wealth may be associated with some of these categories of “happiness,” specifically self-focused positive emotions such as pride and contentment, whereas less wealthy people have more other-focused positive emotions like love and compassion.

In fact, in the Swedish lottery winners study, people’s feelings about their social well-being (with friends, family, neighbors, and society) were no different between lottery winners and regular people.

Money is a means to the things we value, not happiness itself

One major difference between lottery winners and non-winners, it turns out, is that lottery winners have more spare time. This is the thing that really makes me envious , and I would hypothesize that this is the main reason why lottery winners are more satisfied with their life.

Consider this simply: If we had the financial security to spend time on things we enjoy and value, instead of feeling pressured to generate income all the time, why wouldn’t we be happier?

This is good news. It’s a reminder that money, in and of itself, cannot literally buy happiness. It can buy time and peace of mind. It can buy security and aesthetic experiences, and the ability to be generous to your family and friends. It makes room for other things that are important in life.

In fact, the researchers in that lottery winner study used statistical approaches to benchmark how much happiness winning $100,000 brings in the short-term (less than one year) and long-term (more than five years) compared to other major life events. For better or worse, getting married and having a baby each give a bigger short-term happiness boost than winning money, but in the long run, all three of these events have the same impact.

What does this mean? We make of our wealth and our life what we will. This is especially true for the vast majority of the world made up of people struggling to meet basic needs and to rise out of insecurity. We’ve learned that being rich can boost your life satisfaction and make it easier to have positive emotions, so it’s certainly worth your effort to set goals, work hard, and move towards financial health.

But getting rich is not the only way to be happy. You can still earn health, compassion, community, love, pride, connectedness, and so much more, even if you don’t have a lot of zeros in your bank account. After all, the original definition of “wealth” referred to a person’s holistic wellness in life, which means we all have the potential to be wealthy... in body, mind, and soul.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A.. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. . Proceedings of the national academy of sciences. 2010.

Killingsworth, M. A. . Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year .. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021.

Lindqvist, E., Östling, R., & Cesarini, D. . Long-run effects of lottery wealth on psychological well-being. . The Review of Economic Studies. 2020.

Guardiola, J., González‐Gómez, F., García‐Rubio, M. A., & Lendechy‐Grajales, Á.. Does higher income equal higher levels of happiness in every society? The case of the Mayan people. . International Journal of Social Welfare. 2013.

Diener, E., Ng, W., Harter, J., & Arora, R. . Wealth and happiness across the world: material prosperity predicts life evaluation, whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. . Journal of personality and social psychology. 2010.

Donnelly, G. E., Zheng, T., Haisley, E., & Norton, M. I.. The amount and source of millionaires’ wealth (moderately) predict their happiness . . Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2018.

Piff, P. K., & Moskowitz, J. P. . Wealth, poverty, and happiness: Social class is differentially associated with positive emotions.. Emotion. 2018.

Jade Wu, Ph.D., is a clinical health psychologist and host of the Savvy Psychologist podcast. She specializes in helping those with sleep problems and anxiety disorders.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

There’s been a fundamental shift in how we define adulthood—and at what pace it occurs. PT’s authors consider how a once iron-clad construct is now up for grabs—and what it means for young people’s mental health today.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

More Proof That Money Can Buy Happiness (or a Life with Less Stress)

It's not about the bigger home or the better vacation. Financial stability helps people escape the everyday hassles of life, says research by Jon Jachimowicz .

Featuring Jon M. Jachimowicz . By Michael Blanding on January 25, 2022 .

When we wonder whether money can buy happiness, we may consider the luxuries it provides, like expensive dinners and lavish vacations. But cash is key in another important way: It helps people avoid many of the day-to-day hassles that cause stress, new research shows.

Money can provide calm and control, allowing us to buy our way out of unforeseen bumps in the road, whether it’s a small nuisance, like dodging a rainstorm by ordering up an Uber, or a bigger worry, like handling an unexpected hospital bill, says Harvard Business School professor Jon Jachimowicz.

“If we only focus on the happiness that money can bring, I think we are missing something,” says Jachimowicz, an assistant professor of business administration in the Organizational Behavior Unit at HBS. “We also need to think about all of the worries that it can free us from.”

The idea that money can reduce stress in everyday life and make people happier impacts not only the poor, but also more affluent Americans living at the edge of their means in a bumpy economy. Indeed, in 2019, one in every four Americans faced financial scarcity, according to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The findings are particularly important now, as inflation eats into the ability of many Americans to afford basic necessities like food and gas, and COVID-19 continues to disrupt the job market.

Buying less stress

The inspiration for researching how money alleviates hardships came from advice that Jachimowicz’s father gave him. After years of living as a struggling graduate student, Jachimowicz received his appointment at HBS and the financial stability that came with it.

“My father said to me, ‘You are going to have to learn how to spend money to fix problems.’” The idea stuck with Jachimowicz, causing him to think differently about even the everyday misfortunes that we all face.

To test the relationship between cash and life satisfaction, Jachimowicz and his colleagues from the University of Southern California, Groningen University, and Columbia Business School conducted a series of experiments, which are outlined in a forthcoming paper in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science , The Sharp Spikes of Poverty: Financial Scarcity Is Related to Higher Levels of Distress Intensity in Daily Life .

Higher income amounts to lower stress

In one study, 522 participants kept a diary for 30 days, tracking daily events and their emotional responses to them. Participants’ incomes in the previous year ranged from less than $10,000 to $150,000 or more. They found:

Money reduces intense stress: There was no significant difference in how often the participants experienced distressing events—no matter their income, they recorded a similar number of daily frustrations. But those with higher incomes experienced less negative intensity from those events.

More money brings greater control : Those with higher incomes felt they had more control over negative events and that control reduced their stress. People with ample incomes felt more agency to deal with whatever hassles may arise.

Higher incomes lead to higher life satisfaction: People with higher incomes were generally more satisfied with their lives.

“It’s not that rich people don’t have problems,” Jachimowicz says, “but having money allows you to fix problems and resolve them more quickly.”

Why cash matters

In another study, researchers presented about 400 participants with daily dilemmas, like finding time to cook meals, getting around in an area with poor public transportation, or working from home among children in tight spaces. They then asked how participants would solve the problem, either using cash to resolve it, or asking friends and family for assistance. The results showed:

People lean on family and friends regardless of income: Jachimowicz and his colleagues found that there was no difference in how often people suggested turning to friends and family for help—for example, by asking a friend for a ride or asking a family member to help with childcare or dinner.

Cash is the answer for people with money: The higher a person’s income, however, the more likely they were to suggest money as a solution to a hassle, for example, by calling an Uber or ordering takeout.

While such results might be expected, Jachimowicz says, people may not consider the extent to which the daily hassles we all face create more stress for cash-strapped individuals—or the way a lack of cash may tax social relationships if people are always asking family and friends for help, rather than using their own money to solve a problem.

“The question is, when problems come your way, to what extent do you feel like you can deal with them, that you can walk through life and know everything is going to be OK,” Jachimowicz says.

Breaking the ‘shame spiral’

In another recent paper , Jachimowicz and colleagues found that people experiencing financial difficulties experience shame, which leads them to avoid dealing with their problems and often makes them worse. Such “shame spirals” stem from a perception that people are to blame for their own lack of money, rather than external environmental and societal factors, the research team says.

“We have normalized this idea that when you are poor, it’s your fault and so you should be ashamed of it,” Jachimowicz says. “At the same time, we’ve structured society in a way that makes it really hard on people who are poor.”

For example, Jachimowicz says, public transportation is often inaccessible and expensive, which affects people who can’t afford cars, and tardy policies at work often penalize people on the lowest end of the pay scale. Changing those deeply-engrained structures—and the way many of us think about financial difficulties—is crucial.

After all, society as a whole may feel the ripple effects of the financial hardships some people face, since financial strain is linked with lower job performance, problems with long-term decision-making, and difficulty with meaningful relationships, the research says. Ultimately, Jachimowicz hopes his work can prompt thinking about systemic change.

“People who are poor should feel like they have some control over their lives, too. Why is that a luxury we only afford to rich people?” Jachimowicz says. “We have to structure organizations and institutions to empower everyone.”

[Image: iStockphoto/mihtiander]

Related reading from the Working Knowledge Archives

Selling Out The American Dream

Article By :

Latest from HBS faculty experts

Expertly curated insights, precisely tailored to address the challenges you are tackling today.

Strategy and Innovation

Social responsibility, diversity and inclusion.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Money Does Not Always Buy Happiness, but Are Richer People Less Happy in Their Daily Lives? It Depends on How You Analyze Income

Laura kudrna, kostadin kushlev.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Begoña Espejo, University of Valencia, Spain

Reviewed by: Leomarich Casinillo, Visayas State University, Philippines; Monica Violeta Achim, Babeș-Bolyai University, Romania; Stefano Zamagni, University of Bologna, Italy

*Correspondence: Laura Kudrna, [email protected]

This article was submitted to Quantitative Psychology and Measurement, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychology

Received 2022 Feb 24; Accepted 2022 Apr 8; Collection date 2022.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Do people who have more money feel happier during their daily activities? Some prior research has found no relationship between income and daily happiness when treating income as a continuous variable in OLS regressions, although results differ between studies. We re-analyzed existing data from the United States and Germany, treating household income as a categorical variable and using lowess and spline regressions to explore nonlinearities. Our analyses reveal that these methodological decisions change the results and conclusions about the relationship between income and happiness. In American and German diary data from 2010 to 2015, results for the continuous treatment of income showed a null relationship with happiness, whereas the categorization of income showed that some of those with higher incomes reported feeling less happy than some of those with lower incomes. Lowess and spline regressions suggested null results overall, and there was no evidence of a relationship between income and happiness in Experience Sampling Methodology (ESM) data. Not all analytic approaches generate the same results, which may contribute to explaining discrepant results in existing studies about the correlates of happiness. Future research should be explicit about their approaches to measuring and analyzing income when studying its relationship with subjective well-being, ideally testing different approaches, and making conclusions based on the pattern of results across approaches.

Keywords: happiness, measurement, time use, income, methodology

Introduction

Does having more money make someone feel happier? The answer to this longstanding question has implications for how individuals live their lives and societies are structured. It is often assumed that more income brings more happiness (with happiness broadly defined herein as hedonic feelings, while recognizing closely related constructs, including satisfaction and eudaimonia; Tiberius, 2006 ; Angner, 2010 ; Dolan and Kudrna, 2016 ; Sunstein, 2021 ). In many aspects of policy, upward income mobility is encouraged, and poverty can result in exclusion, stigmatization, and discrimination by institutions and members of the public. More income provides people with opportunities and, sometimes, capabilities to consume more and thus satisfy more of their preferences, meet their desires and obtain more of what they want and need ( Harsanyi, 1997 ; Sen, 1999 ; Nussbaum, 2008 ). These are all reasons to assume that higher income will bring greater happiness—or, at least, that low income will bring low happiness.

Some research challenges the assumption that earning more should lead to greater happiness. First, because people expect that more money should make them happier, people may feel less happy when their high expectations are not met ( Graham and Pettinato, 2002 ; Nickerson et al., 2003 ) and they may adapt more quickly to more income than they expect ( Aknin et al., 2009 ; Di Tella et al., 2010 ). Second, since the 1980s in many developed countries, the well-educated have had less leisure time than those who are not ( Aguiar and Hurst, 2007 ) and people living in high-earning and well-educated households report feeling more time stress and dissatisfaction with their leisure time ( Hamermesh and Lee, 2007 ; Nikolaev, 2018 ). The quantity of leisure time is not linearly related to happiness, with both too much and too little having a negative association ( Sharif et al., 2021 ). Evidence also shows that people with higher incomes spend more time alone ( Bianchi and Vohs, 2016 ). The lower quality and quantity of leisure and social time of people with higher incomes may, in turn, negatively impact their happiness, especially given there are strong links between social capital or “relational goods” and well-being ( Helliwell and Putnam, 2004 ; Becchetti et al., 2008 ).

At the same time, some—but not all—evidence suggests that working class individuals tend to be more generous and empathetic than more affluent individuals ( Kraus et al., 2010 ; Piff et al., 2010 ; Balakrishnan et al., 2017 ; Macchia and Whillans, 2022 ), and such kindness toward others has been associated with higher well-being ( Dunn et al., 2008 ; Aknin et al., 2012 ). Relatedly, psychological research suggests that people with lower socioeconomic status have a more interdependent sense of self ( Snibbe and Markus, 2005 ; Stephens et al., 2007 ). It is, therefore, possible that people high in income have lower well-being because they experience less of the internal “warm glow” ( Andreoni, 1990 ) benefit that comes along with valuing social relationships and group membership. In theory, therefore, there are reasons to suppose that high income has both benefits and costs for well-being, and empirical evidence can inform the debate about when and whether these different perspectives are supported.

Empirical Evidence on Income and Happiness

The standard finding in existing literature is that higher income predicts greater happiness, but with a declining marginal utility ( Dolan et al., 2008 ; Layard et al., 2008 ): that is, higher income is most closely associated with happiness among those with the least income and is least closely associated with happiness for those with the most income. Recently, this finding has been qualified by studies showing that the relationship between income and happiness depends on how happiness is conceptualized and measured: as an overall evaluation of one’s life or as daily emotional states ( Kahneman and Deaton, 2010 ; Killingsworth, 2021 ). In this vein, authors Kushlev et al. (2015) found no relationship between income and daily happiness in the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), which has recently been found for other happiness measures, too ( Casinillo et al., 2020 , 2021 ) The finding from Kushlev et al. (2015) was replicated in the German Socioeconomic Panel Survey (GSEOP) by Hudson et al. (2016) , and in another analysis of the ATUS by Stone et al. (2018) .

Some research has focused specifically on the effect of high income on happiness. Kahneman and Deaton (2010) conducted regression analyses using a Gallup sample of United States residents, finding that annual income beyond ~$75K was not associated with any higher daily emotional well-being. Income beyond ~$75K, however, predicted better life evaluations. Using a self-selecting sample of experiential data in the United States, Killingsworth (2021) conducted piecewise regressions and found no evidence of satiation or turning points. Jebb et al. (2018) fit regression spline models to global Gallup data, showing that the satiation point in daily experiences found by Kahneman and Deaton (2010) was also apparent in other countries. Unlike Kahneman and Deaton (2010) , however, Jebb et al. (2018) also found evidence of satiation in people’s life evaluations, and even some evidence for “turning points”—whereby richer people evaluated their lives as worse than some of those with lower incomes. A satiation point in life evaluations was also found in European countries at around €28K annually ( Muresan et al., 2020 ).

This pattern of findings could partly depend on the choice of analytic strategy. In analyses of the same dataset as Jebb et al. (2018) but using lowess regression, researchers found no evidence of satiation or turning points in the relationship between income and people’s life evaluations ( Sacks et al., 2012 ; Stevenson and Wolfers, 2012 ). These conflicting results suggest that the effect of analytic strategy on results deserves a closer examination.

The Research Gap

While there has been much research on income and happiness, including according to how happiness is defined and measured, we are not away of any studies that have compared the relationship between income and happiness according to how income is defined and measured. We propose that the relationship between income and happiness may depend not only on how happiness is measured, but also on how income is measured and analyzed. To improve our knowledge of the relationship between income and happiness, this paper, we focus on nonlinearities in the relationship between income and happiness and re-analyze the ATUS data used by Kushlev et al. (2015) and Stone et al. (2018) , as well as the GSOEP data used by Hudson et al. (2016) . Specifically, while Kushlev et al. (2015) analyzed income as a continuous variable in the ATUS, we treat income the way it was measured: as a categorical variable. We compare these results to GSOEP data where we re-code the original continuous measure of income into categorical quantiles. To further explore nonlinearities in the relationship between income and happiness, we also conduct local linear “lowess” and spline regression analyses.

We chose to re-analyze these data to address the question of differences in the relationship between income and happiness according to the measurement and analysis of income because the ATUS and GSOEP provide nationally representative data on people’s feelings as experienced during specific “episodes” of the day after asking them to reconstruct what they did during the entire day. Thus, compared to data from Gallup, which measures affect “yesterday,” measurements in the ATUS are more grounded in specific experiences, and therefore, less subject to recall bias ( Kahneman et al., 2004 ). And unlike Gallup, which uses more crude, dichotomous (“yes-no”) response scales, ATUS measures happiness along a standard seven-point Likert-type scale. In the GSOEP, we were also able to analyze data from the Experience Sampling Methodology (ESM), which asks people how they are feeling during specific episodes during the day and, as such, is even more grounded in specific experiences.

Measuring and Analyzing Income

The original ATUS income variable—family income—contains 16 uneven categories (see Table 1 ). For example, Category 11 has a range of ~$10K, whereas Category 14 has a range of ~$25K. The increasingly larger categories are designed to reflect declining marginal utility as an innate quality of income. Based on this, Kushlev et al. (2015) analyzed income as a continuous variable using the original uneven categories. Continuous scales, however, assume equal intervals between scale points—a strong assumption to make for the relatively arbitrary rate of change in the category ranges. Is increasing one’s income from $20,000 to $25,000 really equidistant to increasing it from $35,000 to $40,000 ( Table 1 )? And can we really assume, for example, that adding $5,000 of additional income to $35,000 is the same as adding $10,000 of additional income to $40,000? Recognizing this issue, income researchers have adopted alternative strategies. For example, Stone et al. (2018) took the midpoints of each category of income, and then log-transformed it. Thus, they transformed the categorical measure of income into a continuous measure. This approach produced results for happiness consistent with the findings of Kushlev et al. (2015) .

The original categories of income in the ATUS family income measure with number of individuals in each income category in the ATUS 2010, 2012, and 2013 well-being modules.

Complete cases only for all variables analyzed.

Both the increasing ranges of the income scale itself and its log-transformations reflect an assumed declining marginal utility of income: They treat a given amount of income increase at the higher end of the income distribution as having less utility than the same amount at the lower end of the distribution. But by subsuming income’s declining utility in its very measurement (or transformation thereof), it becomes difficult to interpret a null relationship with happiness. In other words, we might not be seeing a declining marginal utility of income reflected on happiness because the income variable itself reflects its declining utility.

Even when the income variable itself does not reflect its declining utility, a null relationship between income and daily experiences of happiness has been observed. Hudson et al. (2016) used GSOEP, which contains a measure of income that is continuous in its original form. Whether analyzing this income measure in its raw original form or in transformed log and quadratic forms, a null relationship with happiness was observed. This approach, however, does not consider whether there might be nonlinear/log/quadratic turning or satiation points at higher levels of income—an issue also applicable to previous analyses of ATUS ( Kushlev et al., 2015 ; Stone et al., 2018 ). This is important because there are theoretically both benefits and costs to achieving higher levels of income that could occur at various levels of income; however, this possibility has not yet been fully explored in ATUS or GSOEP data.

In sum, past research using ATUS has treated categorically measured income as a continuous variable, either assuming equidistance between scale points or attempting to create equidistance through statistical transformations. By doing so, however, researchers may have statistically accounted for the very utility of income for happiness that they are trying to test. In both ATUS and GSOEP, the question of whether there might be satiation and/or turning points at higher levels of income has not been fully considered. The present research explores whether treating income as a categorical variable in both ATUS and GSOEP would replicate past findings or reveal novel insights, focusing on possible nonlinearities in the relationship between income and happiness.

Materials and Methods

We used data from ATUS well-being modules in 2010, 2012, and 2013. To facilitate future replications of this research, the ATUS extract builder was used to create the dataset ( Hofferth et al., 2017 ). 1 The ATUS is a repeated cross-sectional survey and is nationally representative of United States household residents aged 15 years and older. Its sampling frame is the Current Population Survey (CPS), which was conducted 2–5 months prior to the ATUS. Some items in the ATUS come from the CPS, including the household income item that we analyze.

Data from the GSOEP come from the Innovation Sample (IS), which is a subsample of the larger main GSOEP ( Richter and Schupp, 2015 ). The main GSOEP and the IS are designed to be nationally representative. The IS contains information on household residents aged 17 years of age and older. We used two modules from these data: the 2012–2015 DRM module, which is a longitudinal survey, and the 2014–2015 ESM module.

Outcome Measures

In ATUS, participants were called on the phone and asked how they spent their time yesterday: what activities they were doing, for how long, who they spent time with and where they were located. This information was used to create their time use diary. A random selection of three activities were taken from these diaries and participants were asked how they felt during them. The feelings items were tired, sad, stressed, pain, and happy. Participants were also asked how meaningful what they were doing felt.

In GSOEP, participants were interviewed face to face for the DRM questions and through smartphones for the ESM questions. In the DRM, as in the ATUS, they were asked how they spent their time yesterday and, for a random selection of three activities, they were asked further details about how they felt. In the ESM, participants were randomly notified on mobile phones at seven random points during the day for around 1 week. As in the DRM, they were asked how they were spending their time at the point of notification, as well as how they felt. Participants in both ESM and DRM samples were asked about whether they were feeling happy, as well as other emotions such as sadness, stress, and boredom.

The focus of this research is on the happiness items from both the ATUS and GSOEP to highlight differences according to the treatment of the independent measure of income rather than differences according to the dependent outcome of emotional well-being.

Data were analyzed in STATA 15 and jamovi. The Supplementary Material S1 file contains the STATA command file for the main commands written to analyze the data. In both ATUS and GSOEP, OLS regressions were conducted with happiness as the outcome measure and income as the explanatory measure. Following Kushlev et al. (2015) and Hudson et al. (2016) , the average happiness across all activities each day was taken to create an individual-level measure. Because the GSOEP DRM sample contained multiple observations across years, the SEs were clustered at the individual level for models using this dataset.

The treatment of income differed according to the dataset because income was collected differently in each dataset. In the ATUS, income was first analyzed in continuous, log, and quadratic forms in OLS regressions, as in other research ( Kushlev et al., 2015 ; Hudson et al., 2016 ). Next, it was analyzed as a categorical variable with 16 categories, preserving the identical format that it was originally collected in from the CPS questionnaire.

In GSOEP, the income variable in the dataset is provided in continuous form because participants reported their monthly income as an integer. To compare to the ATUS results, 16 quantiles of income were created and analyzed in GSOEP DRMs (see Table 2 - note that there were insufficient observations to conduct these analyses with GSOEP ESMs). This income variable was also analyzed in continuous, log, and quadratic forms.

The range and number of person-year observations of the GSOEP Income 4 variable divided into 16 quantiles.

Omnibus F -tests and effect sizes ( n 2 ) are also reported to compare the categorical, continuous, log, and quadratic approaches.

We conducted lowess and spline regressions to further investigate possible nonlinearities in the relationship between income and happiness. For the lowess regressions, the smoothing parameter was set at of 0.08. For the regression splines, we fitted knots at four quartiles and five quantiles of income. We also used the results of OLS regressions treating income as a categorical variable, as well as the results of the lowess regression treating income as continuous, to fit knots at pre-specified values of income (where these analyses suggested there could be turning and/or satiation points).

Complete case analyses were conducted with 33,976 individuals in ATUS, 6,766 individuals in German DRMs, and 249 individuals in German ESMs. There was item-missing data in some samples (ATUS, 1.7% missing; GSOEP DRMs, 8.2% missing; GSOEP ESMs data, and 6.0% missing). We make analytical and not population inferences and therefore do not use survey weights ( Pfeffermann, 1996 ).

Results are presented without and with controls for demographic and diary characteristics. Following Kushlev et al. (2015) , Hudson et al. (2016) , and Stone et al. (2018) , these controls were age, gender, marital status, ethnic background, 2 health, 3 employment status, children, 4 and whether the day was a weekend. We also control for the year of the survey in ATUS DRM data to address the issue that our results are not due to new data but rather how we treat the income variable.

The list of variables we use in analyses are in Table 3 .

List of variables used in analyses in ATUS and GSOEP.

In both ATUS and GSOEP, daily happiness was analyzed using a 0–6 scale (in GSOEP scale points 1–7 were recoded to 0–6 to match ATUS). The ATUS mean happiness was 4.38 (SD = 1.33). The GSOEP DRM mean happiness was 2.91 (SD = 1.46), and the GSOEP ESM mean happiness was 2.65 (SD = 1.03).

The magnitude of our results can be considered in the context of effect sizes from other research on demographic characteristics and daily happiness ( Kahneman et al., 2004 ; Stone et al., 2010 ; Luhmann et al., 2012 ; Hudson et al., 2019 ). For example, the effect size for the relationship between age and daily experiences of happiness was 0.16 in Stone et al. (2010) . Our effect sizes range from 0.06 to 0.37. Throughout, we focus on coefficients, their 95% CIs, and visualizations of these coefficients and CIs, rather than on their statistical significance ( Lakens, 2021 ). The purpose of this is to highlight how analytic treatments of income affect the magnitude and precision of the relationship between income and happiness.

When treating the 16-category family income variable as continuous in OLS regressions, there was no substantive relationship between income and happiness as in other prior research ( Kushlev et al., 2015 ; Hudson et al., 2016 ; Stone et al., 2018 ). Out of the linear, squared, and log coefficients without and with controls, the largest and most precise coefficients were with controls; for linear income it was ( b = −0.006, 95% CI = −0.01, −0.002), squared income ( b = −0.0001, 95% CI = 0.0003, 0.00006), and log income ( b = −0.03, 95% CI = −0.05, 0.001). The omnibus F -test (without controls) for linear income was F = 0.28, n 2 = 0.000008 (95% CI = 0.00, 0.0002), for income squared was F = 1.60, n 2 = 0.00005 (95% CI = 0.00, 0.0003), and for log income was F = 0.23, n 2 = 0.000006 (95% CI = 0.00,0.0002).

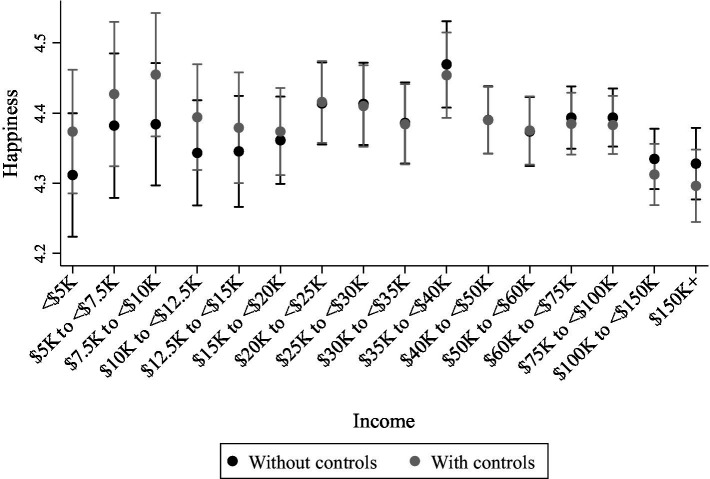

The categorization of income focused attention on those with incomes of $35–40K, who appeared substantively happier than some of those with higher incomes (and lower incomes; see Figure 1 ). For example, with controls, those with incomes of $35–40K appeared happier relative to those with incomes of $150K+ ( b = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.08, 0.24) and $100–150K ( b = 0.14, 95% CI: 0.07, 0.221). The omnibus test for categorical income was F = 1.61, n 2 = 0.007 (95% CI = 0.00, 0.0009).

Predicted values of average individual happiness in the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) at the 16 values of the family income variable without and with controls. Covariates at means. 95% CI.

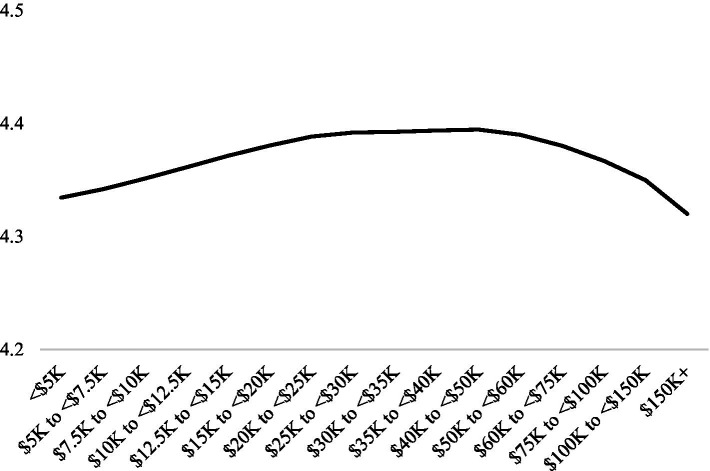

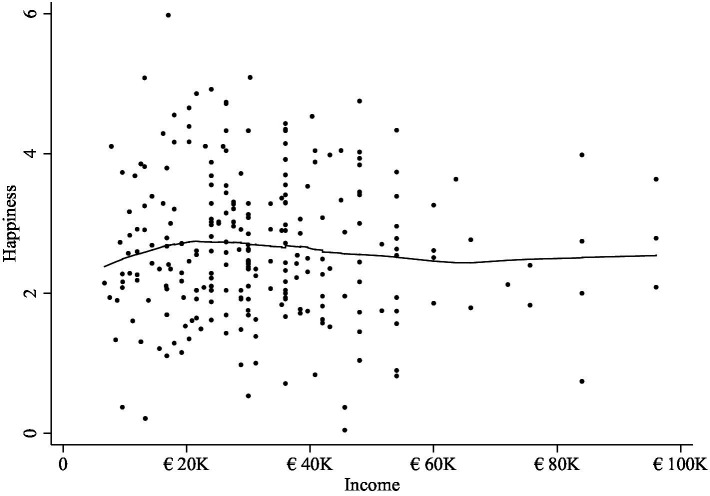

Results from regression splines and a lowess regression suggested null results overall (see Figure 2 ). Further details of the analyses are in Supplementary Material S2 .

Line graph of predicted values from lowess regressions explaining variance in happiness from income treated as a continuous variable in ATUS.

When treating the continuous household income variable as continuous (in €10,000s) in OLS regressions, there was no substantive relationship between income and happiness as in other prior research ( Kushlev et al., 2015 ; Hudson et al., 2016 ; Stone et al., 2018 ). The association with the largest magnitude and most precision was for log income with controls ( b = −0.08, 95% CI = −0.18, 0.01). 5

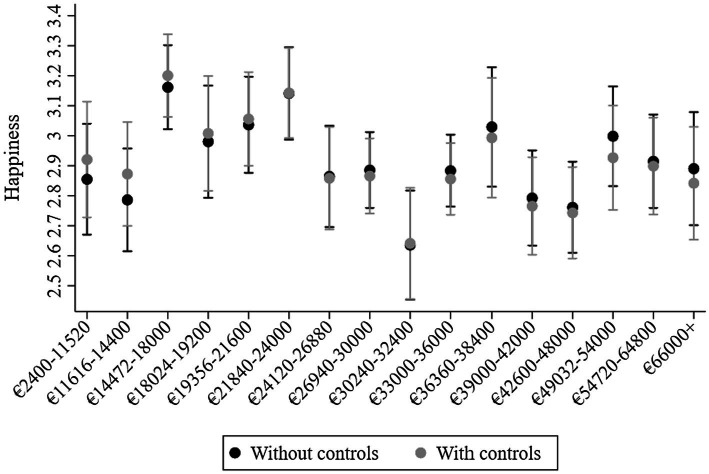

As in ATUS, treating the variable as categorical suggested some relationships between income and happiness. These results drew attention to those third quantile (~€14–18K), who seemed happier than those both higher and lower in income (see Figure 3 ). For example, with controls, they were happier than those in quantiles 13 (€42.6–48K, b = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.25, 0.67), seven (~€24–27K, b = 0.34, 95% CI = 0.13, 0.56), and one (€2.40–11,520K, b = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.05, 0.51). The omnibus test for categorical income was F = 4.00, n 2 = 0.009 (95% CI = 0.003, 0.01), whereas the omnibus test for linear income was F = 0.09, n 2 = 0.00001 (95% CI = 0.00, 0.0007). The omnibus for log income was F = 1.42, n 2 = 0.0002 (95% CI = 0.00, 0.0001) and for income squared it was F = 0.96, n 2 = 0.0001 (95% CI = 0.00, 0.001).

Predicted values of average person-year happiness from GSOEP DRMs at 16 quantiles of income (Income 4) without and with controls. Covariates at means. 95% CI.

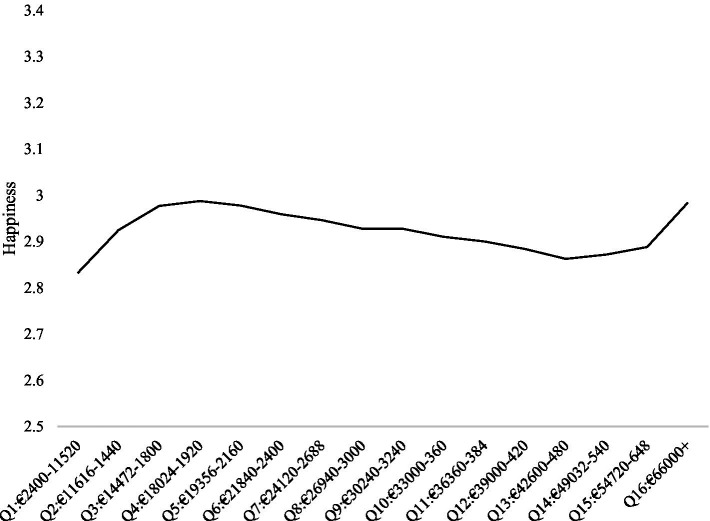

The lowess and spline regressions suggested null results overall, as the coefficients were small in magnitude (see Figure 4 ). Further details of the analyses are in Supplementary Material S3 .

Line graph of predicted values from lowess regressions explaining variance in happiness from income treated as a continuous variable in GSOEP DRMs at 16 quantiles of income.

There was no evidence to suggest any substantive association between income and happiness in ESM data for linear income, income squared, log income, in the lowess regressions, or regression splines. A visualization of the lowess results are in Figure 5 and further details of the analyses are in Supplementary Material S4 .

Results of local linear “lowess” regression from GSOEP Experience Sampling Methodology (ESM) data with happiness as the outcome and continuous annual income as the explanatory variable.

The omnibus F -test for linear income was F = 0.53, n 2 = 0.002 (95%CI = −0.00, 0.03), and for log income it was F = 0.12, n 2 = 0.0005, 95%CI = 0.00, 0.02. For income squared it was F = 0.63, n 2 = 0.003, 95%CI = 0.00 0.03.

Is income creating a signal in these data on daily experiences of happiness, or is it all simply noise? The present results suggest that whether income can be concluded as being associated with daily experiences of happiness may depend on how income is analyzed. When income in ATUS is analyzed in its original, categorical form, there is some evidence that some people with higher incomes feel somewhat less happy than some of those with lower incomes. When the continuous income variable in GSOEP is split into categories, a similar pattern is observed. This is not inconsistent with the findings of Kushlev et al. (2015) , Hudson et al. (2016) , and Stone et al. (2018) , who found no relationship between income and daily feelings of happiness in the same data when income was analyzed as a continuous variable. It simply illustrates that a relationship between income and happiness could be interpreted when treating income categorically rather than continuously.

There are at least three possible interpretations to our overall results. One interpretation tends toward conservative. We conducted multiple comparisons of many transformations of income, which might inspire some to question whether we should have accounted for this in some way by adjusting for multiple comparisons. Although we found some evidence of differences in happiness according to income, such an adjustment might lead to an overall null conclusion when characterizing the relationship between income on happiness. A second interpretation is more generous. Within this perspective, one might emphasize the fact that because our income measures were correlated, no correction for multiple comparisons was required. It could then be argued that because we found some evidence for the relationship between income on happiness, there is good evidence that the overall effect is not null. A more moderate perspective, and the one adopted in this paper, is that because the overall pattern of our results showed mixed null and nonnull results, we can make an overall conclusion of some differences in happiness according to income. We also noticed that equivalizing income in the German data strengthened the relationship of income and happiness, further supporting the conclusion of some differences—and that the analytic treatment of income matters.

Based on the moderate perspective, we conclude that there is very little evidence of any relationship between income and daily experiences of happiness—and any relationship that does exist would suggest higher income could be associated with less happiness. The results do not support the results of Sacks et al. (2012) or Killingsworth (2021) , where a greater income was associated with greater happiness, and there were no satiation or turning points (see also Stevenson and Wolfers, 2012 ). These results are more aligned with Kahneman and Deaton (2010) , who found a satiation point in the relationship between income daily experiences of happiness, researchers finding no association between income and happiness ( Kushlev et al., 2015 ; Jebb et al., 2018 ; Casinillo et al., 2020 , 2021 ), who found that higher income can be associated with worse evaluations of life. We suggest the analytic strategy for income could contribute to explaining discrepant results in existing literature, and researchers should be clear about the approaches they have tested, although we acknowledge that sampling differences could play a role, too.

Overall, the results were broadly consistent between countries because there was no substantive relationship between income and happiness when income was treated continuously but there appeared to be relationships when treating income categorically. Despite a similar overall pattern in the income results, there were other difference between countries. German residents rated their happiness as lower than United States residents (a difference of ~1.5 scale points out of seven). This could be because of different interpretations of the word “happiness” in Germany and the United States. The word for happiness in German used in the survey— glück —can mean something more akin to lucky or optimistic—which is different from the meaning of word “happy” in the United States. Despite this linguistic difference, those with higher incomes were still less happy than some of those with lower incomes in both samples.

Limitations

One limitation to our results is the representativeness of the income distribution. Household surveys like those that we used do not tend to capture the “tails” of the income distribution very well: People in institutions and without addresses are excluded from these sample populations, which omits populations such as those living in nursing homes and prisons, as well as the homeless. Moreover, people do not always self-report their income accurately due to issues such as social desirability bias ( Angel et al., 2019 ). Existing studies that have focused on those with very low incomes do tend to find that low income is associated with low happiness ( Diener and Biswas-Diener, 2002 ; Clark et al., 2016 ; Adesanya et al., 2017 ). In ATUS, the highest household income value available was $150K, whereas in GSOEP it was €360K. Thus, it is not always clear whether the very affluent, such as millionaires, are represented in these samples ( Smeets et al., 2020 ). Overall, our results cannot be taken as representative of people who are very poor or rich and should not be interpreted as such.

Another limitation is that the present results cannot be interpreted casually because there has been no manipulation of income in these data nor exploration of mechanisms and there was no longitudinal data in ATUS. As discussed by Kushlev et al. (2015) , there are issues such as reverse causality. Here, however, some of our results potentially suggest an alternative reverse causality pathway, whereby less happy people may select into earning more income. Because the counterfactual is not apparent—we do not know how happy people with high incomes would be without their higher income—it could also be that those with high incomes would be even less happy than they currently are if they had not attained their current level of income. In other words, people with high incomes may have started out as less happy in the first place and be even less happy if they did not have high incomes.

A further limitation is the time period of the data, especially that they were collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. This could be an issue because it is possible that the relationship between income and daily experiences of happiness has changed, such as due to the exacerbation of health inequalities and restrictions on freedom of movement due to nationwide lockdowns. Our study does not provide any information on the longer-term and health and well-being consequences of both COVID-19 itself and the policy response to COVID-19 ( Aknin et al., 2022 ). As one example, access to green space, which has health and well-being benefits, is lower among those with low income, and this mechanism between income and happiness may have become more salient during COVID-19 ( Geary et al., 2021 ). Overall, it is important to consider the regional, political, and socioeconomic contexts in which income is attained to understand its relationship with well-being, including levels of income in reference groups such as neighbors, friends, and colleagues ( Luttmer, 2005 ; De Neve and Sachs, 2020 ). It would be important to replicate the results in this research with more recent data to address the limitation that the data we used are not recent, considering our broader point that the measurement and analysis of income should be considered as carefully as the measurement and analysis of happiness.

Future Directions

This research points to several directions for future research. One direction relates to data and measures: Nonlinearities in the relationship between income and happiness could be examined using time use data from other countries, considered between countries and/or within countries over time ( Deaton et al., 2008 ; De Neve et al., 2018 ), and investigated for measures of emotional states other than happiness ( Piff and Moskowitz, 2018 ). In general, our results suggest that researchers should pay attention to how income is measured and analyzed when considering how it is related to happiness, which complements findings from other research that the way happiness is measured and analyzed is important ( Kahneman and Deaton, 2010 ; Jebb et al., 2018 ).

Future research could also explore mechanisms that may explain our findings. In addition to those mentioned in the Introduction—expectations ( Graham and Pettinato, 2002 ; Nickerson et al., 2003 ), time use ( Aguiar and Hurst, 2007 ; Hamermesh and Lee, 2007 ; Bianchi and Vohs, 2016 ; Nikolaev, 2018 ; Sharif et al., 2021 ); generosity ( Dunn et al., 2008 ; Kraus et al., 2010 ; Piff et al., 2010 ; Aknin et al., 2012 ; Balakrishnan et al., 2017 ; Macchia and Whillans, 2022 ), and sense of self ( Snibbe and Markus, 2005 ; Stephens et al., 2007 )—another is the identity-related effect of transitioning between socioeconomic groups. Though one might expect upward mobility to be associated with greater happiness, research suggests that some working class people do not wish to become upwardly mobile because it could lead to a loss of identity and change in community ( Akerlof, 1997 ; Friedman, 2014 ). Indeed, upward intergenerational mobility is associated with worse life evaluations in the United Kingdom—though not in Switzerland ( Hadjar and Samuel, 2015 ), although recent findings show substantial negative effects of downward mobility, too ( Dolan and Lordan, 2021 ). Over time, therefore, the degree of mobility in a population could influence the relationship between income and happiness in both positive and negative directions.

Additionally, social comparisons could drive the effects of higher income on happiness. Higher income might not benefit happiness if one’s reference group—that is, the people to whom we compare or have knowledge of in some form ( Hyman, 1942 ; Shibutani, 1955 ; Runciman, 1966 )—changes with higher socioeconomic status. As income increases, people might compare themselves to others who are also doing similarly or better to them, and then not feel or think that they are doing any better by comparison—or even feel worse ( Cheung and Lucas, 2016 ). This is one of the explanations for the well-known “Easterlin Paradox” ( Easterlin, 1974 ), which suggests that as national income rises people do not become happier because they compare their achievements to others. The paradox is debated ( Sacks et al., 2012 ). Additionally, some research shows that it is possible to view others’ greater success as one’s own future opportunity and for upward social comparisons to then positively impact upon well-being ( Senik, 2004 ; Davis and Wu, 2014 ; Ifcher et al., 2018 ). As with the role of mobility in the relationship between income and happiness, it is unclear whether the role of social comparisons would create a positive or negative impact over time and future research could explore this.

Final Remarks

Overall, our results provide some evidence that individual attainment in terms of income may not equate to the attainment of individual happiness—and could even be associated with less daily happiness, depending upon how income is measured and analyzed. These results suggest that how income is associated with happiness depends on how income is measured and analyzed. They provide some support to the idea that financial achievement can have both costs and benefits, potentially informing normative discussions about the optimal distribution of income in society.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found at: https://www.atusdata.org (The ATUS extract builder was used to create the ATUS dataset, see Hofferth et al., 2017 ). GSOEP data were requested from https://www.diw.de/en/diw_02.c.222516.en/data.html , see Richter and Schupp, 2015 .

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

LK and KK contributed to conception and design of the study. LK organized the data, performed the statistical analysis in STATA, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KK performed additional statistical analysis in jamovi and wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

LK was supported by a London School of Economics PhD scholarship during early work and later by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) West Midlands. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

LK thanks Professor Paul Dolan and Dr Georgios Kavetsos for their support early on in conducting this research, as well as Professor Richard Lilford for insights about multiple comparisons.

1 https://www.atusdata.org

2 In the ATUS this was Hispanic and Black, in GSOEP this was German origin.

3 In the ATUS this was whether the respondent had any physical or cognitive difficulty (yes/no), in GSOEP this was self-rated general health (bad, poor, satisfactory, good, and very good).

4 In the ATUS this was presence of children <18 years in the household, in GSOEP this was number of children.

5 This association was stronger and more precise when equivalizing income (dividing by the square root of household size), b = −0.16, 95%CI = −0.06, −0.27, underscoring the importance of transparency in the treatment of income.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.883137/full#supplementary-material

- Adesanya O., Rojas B. M., Darboe A., Beogo I. (2017). Socioeconomic differential in self-assessment of health and happiness in 5 African countries: finding from world value survey. PLoS One 12:e0188281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188281, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aguiar M., Hurst E. (2007). Measuring trends in leisure: the allocation of time over five decades. Q. J. Econ. 122, 969–1006. doi: 10.1162/qjec.122.3.969 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Akerlof G. A. (1997). Social distance and social decisions. Econometrica 65, 1005–1027. doi: 10.2307/2171877 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aknin L. B., De Neve J. E., Dunn E. W., Fancourt D. E., Goldberg E., Helliwell J. F., et al. (2022). Mental health during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: a review and recommendations for moving forward. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 19:17456916211029964. doi: 10.1177/17456916211029964, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aknin L. B., Hamlin J. K., Dunn E. W. (2012). Giving leads to happiness in young children. PLoS One 7:e39211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039211, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aknin L. B., Norton M. I., Dunn E. W. (2009). From wealth to well-being? Money matters, but less than people think. J. Posit. Psychol. 4, 523–527. doi: 10.1080/17439760903271421 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Andreoni J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: a theory of warm-glow giving. Econ. J. 100, 464–477. doi: 10.2307/2234133 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Angel S., Disslbacher F., Humer S., Schnetzer M. (2019). What did you really earn last year? Explaining measurement error in survey income data. J. R. Stat. Soc. A. Stat. Soc. 182, 1411–1437. doi: 10.1111/rssa.12463 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Angner E. (2010). Subjective well-being. J. Socio-Econ. 39, 361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2009.12.001 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Balakrishnan A., Palma P. A., Patenaude J., Campbell L. (2017). A 4-study replication of the moderating effects of greed on socioeconomic status and unethical behaviour. Sci. Data 4:160120. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.120, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Becchetti L., Pelloni A., Rossetti F. (2008). Relational goods, sociability, and happiness. Kyklos 61, 343–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6435.2008.00405.x [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bianchi E. C., Vohs K. D. (2016). Social class and social worlds: income predicts the frequency and nature of social contact. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 7, 479–486. doi: 10.1177/1948550616641472 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Casinillo L. F., Casinillo E. L., Aure M. R. K. L. (2021). Economics of happiness: a social study on determinants of well-being among employees in a state university. Philippine Soc. Sci. J. 4, 42–52. doi: 10.52006/main.v4i1.316 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Casinillo L. F., Casinillo E. L., Casinillo M. F. (2020). On happiness in teaching: an ordered logit modeling approach. JPI 9, 290–300. doi: 10.23887/jpi-undiksha.v9i2.25630 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cheung F., Lucas R. E. (2016). Income inequality is associated with stronger social comparison effects: the effect of relative income on life satisfaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 110, 332–341. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000059, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clark A. E., D’Ambrosio C., Ghislandi S. (2016). Adaptation to poverty in long-run panel data. Rev. Econ. Stat. 98, 591–600. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00544, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis L., Wu S. (2014). Social comparisons and life satisfaction across racial and ethnic groups: the effects of status, information and solidarity. Soc. Indic. Res. 117, 849–869. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0367-y [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Neve J. E., Sachs J. D. (2020). The SDGs and human well-being: a global analysis of synergies, trade-offs, and regional differences. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71916-9, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Neve J. E., Ward G., De Keulenaer F., Van Landeghem B., Kavetsos G., Norton M. I. (2018). The asymmetric experience of positive and negative economic growth: global evidence using subjective well-being data. Rev. Econ. Stat. 100, 362–375. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00697, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Deaton A. (2008). Income, health, and well-being around the world: evidence from the Gallup world poll. J. Econ. Perspect. 22, 53–72. doi: 10.1257/jep.22.2.53, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Di Tella R., Haisken-De New J., MacCulloch R. (2010). Happiness adaptation to income and to status in an individual panel. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 76, 834–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2010.09.016 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Diener E., Biswas-Diener R. (2002). Will money increase subjective well-being? Soc. Indic. Res. 57, 119–169. doi: 10.1023/A:1014411319119 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dolan P., Kudrna L. (2016). “Sentimental hedonism: pleasure, purpose, and public policy” in International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life. Handbook of Eudemonic Well-Being. ed. Vittersø J. (Springer International Publishing AG; ), 437–452. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dolan P., Lordan G. (2021). Climbing up ladders and sliding down snakes: an empirical assessment of the effect of social mobility on subjective wellbeing. Rev. Econ. Househ. 19, 1023–1045. doi: 10.1007/s11150-020-09487-x [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dolan P., Peasgood T., White M. (2008). Do we realy know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literaure on the factors associated with subjective well-being. J. Econ. Psychol. 29, 94–122. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2007.09.001 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunn E. W., Aknin L. B., Norton M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science 319, 1687–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1150952, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Easterlin R. A. (1974). “Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence,” in Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramowitz. eds. David P. A., Reder M. W. (New York: Academic Press, Inc.). [ Google Scholar ]

- Friedman S. (2014). The price of the ticket: rethinking the experience of social mobility. Sociology 48, 352–368. doi: 10.1177/0038038513490355 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Geary R. S., Wheeler B., Lovell R., Jepson R., Hunter R., Rodgers S. (2021). A call to action: improving urban green spaces to reduce health inequalities exacerbated by COVID-19. Prev. Med. 145:106425. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106425, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Graham C., Pettinato S. (2002). Frustrated achievers: winners, losers and subjective well-being in new market economies. J. Dev. Stud. 38, 100–140. doi: 10.1080/00220380412331322431 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hadjar A., Samuel R. (2015). Does upward social mobility increase life satisfaction? A longitudinal analysis using British and Swiss panel data. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 39, 48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2014.12.002 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hamermesh D. S., Lee J. (2007). Stressed out on four continents: time crunch or yuppie kvetch? Rev. Econ. Stat. 89, 374–383. doi: 10.1162/rest.89.2.374 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harsanyi J. C. (1997). Utilities, preferences, and substantive goods. Soc. Choice Welf. 14, 129–145. [ Google Scholar ]

- Helliwell J. F., Putnam R. D. (2004). The social context of well–being. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 359, 1435–1446. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1522, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hofferth S., Flood S., Sobek M. (2017). American time use survey data extract system: version 26 [machine-readable database]. College Park, MD: University of Maryland and Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

- Hudson N. W., Lucas R. E., Donnellan M. B. (2019). Healthier and happier? A 3-year longitudinal investigation of the prospective associations and concurrent changes in health and experiential well-being. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 45, 1635–1650. doi: 10.1177/0146167219838547, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hudson N. W., Lucas R. E., Donnellan M. B., Kushlev K. (2016). Income reliably predicts daily sadness, but not happiness: a replication and extension of Kushlev, Dunn, and Lucas (2015). Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 7, 828–836. doi: 10.1177/1948550616657599, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hyman H. H. (1942). “The psychology of status,” in Archives of Psychology (Columbia University; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Ifcher J., Zarghamee H., Graham C. (2018). Local neighbors as positives, regional neighbors as negatives: competing channels in the relationship between others’ income, health, and happiness. J. Health Econ. 57, 263–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.08.003, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jebb A. T., Tay L., Diener E., Oishi S. (2018). Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 33–38. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0277-0, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kahneman D., Deaton A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 16489–16493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011492107, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kahneman D., Krueger A., Schkade D., Schwarz N., Stone A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: the day reconstruction method. Science 306, 1776–1780. doi: 10.1126/science.1103572, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Killingsworth M. A. (2021). Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118:e2016976118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2016976118, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kraus M. W., Côté S., Keltner D. (2010). Social class, contextualism, and empathic accuracy. Psychol. Sci. 21, 1716–1723. doi: 10.1177/0956797610387613, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kushlev K., Dunn E. W., Lucas R. E. (2015). Higher income is associated with less daily sadness but not more daily happiness. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 6, 483–489. doi: 10.1177/1948550614568161 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lakens D. (2021). The practical alternative to the p value is the correctly used p value. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 16, 639–648. doi: 10.1177/1745691620958012, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Layard R., Mayraz G., Nickell S. (2008). The marginal utility of income. J. Public Econ. 92, 1846–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.01.007 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luhmann M., Hofmann W., Eid M., Lucas R. E. (2012). Subjective well-being and adaptation to life events: a meta-analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 592–615. doi: 10.1037/a0025948, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luttmer E. F. (2005). Neighbors as negatives: relative earnings and well-being. Q. J. Econ. 120, 963–1002. doi: 10.1162/003355305774268255 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Macchia L., Whillans A. V. (2022). The link between income, income inequality, and prosocial behavior around the world. Soc. Psychol. 52, 375–386. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000466 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Muresan G. M., Ciumas C., Achim M. V. (2020). Can money buy happiness? Evidence for European countries. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 15, 953–970. doi: 10.1007/s11482-019-09714-3 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nickerson C., Schwarz N., Diener E., Kahneman D. (2003). Zeroing in on the dark side of the American dream: a closer look at the negative consequences of the goal for financial success. Psychol. Sci. 14, 531–536. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1461.x, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nikolaev B. (2018). Does higher education increase hedonic and eudaimonic happiness? J. Happiness Stud. 19, 483–504. doi: 10.1007/s10902-016-9833-y [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nussbaum M. C. (2008). Who is the happy warrior? Philosophy poses questions to psychology. J. Leg. Stud. 37, S81–S113. doi: 10.1086/587438 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pfeffermann D. (1996). The use of sampling weights for survey data analysis. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 5, 239–261. doi: 10.1177/096228029600500303, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Piff P. K., Kraus M. W., Côté S., Cheng B. H., Keltner D. (2010). Having less, giving more: the influence of social class on prosocial behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 99, 771–784. doi: 10.1037/a0020092, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Piff P. K., Moskowitz J. P. (2018). Wealth, poverty, and happiness: social class is differentially associated with positive emotions. Emotion 18, 902–905. doi: 10.1037/emo0000387, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Richter D., Schupp J. (2015). The SOEP innovation sample (SOEP IS). Schmollers Jahr. 135, 389–399. doi: 10.3790/schm1353389 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Runciman W. (1966). Relative Deprivation, Social Justice: Study Attitudes Social Inequality in 20th Century England. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sacks D. W., Stevenson B., Wolfers J. (2012). The new stylized facts about income and subjective well-being. Emotion 12, 1181–1187. doi: 10.1037/a0029873, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sen A. (1999). Development as Freedom. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [ Google Scholar ]

- Senik C. (2004). When information dominates comparison: learning from Russian subjective panel data. J. Public Econ. 88, 2099–2123. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(03)00066-5 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sharif M. A., Mogilner C., Hershfield H. E. (2021). Having too little or too much time is linked to lower subjective well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 121, 933–947., PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shibutani T. (1955). Reference groups as perspectives. Am. J. Sociol. 60, 562–569. doi: 10.1086/221630 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smeets P., Whillans A., Bekkers R., Norton M. I. (2020). Time use and happiness of millionaires: evidence from the Netherlands. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 11, 295–307. doi: 10.1177/1948550619854751 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Snibbe A. C., Markus H. R. (2005). You can't always get what you want: educational attainment, agency, and choice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 88, 703–720. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.703, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stephens N. M., Markus H. R., Townsend S. (2007). Choice as an act of meaning: the case of social class. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 93, 814–830. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.814, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stevenson B., Wolfers J. (2012). Subjective well-being and income: is there any evidence of satiation? Am. Econ. Rev. 103, 598–604. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.3.598 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stone A., Schneider S., Krueger A., Schwartz J. E., Deaton A. (2018). Experiential wellbeing data from the American time use survey: comparisons with other methods and analytic illustrations with age and income. Soc. Indic. Res. 136, 359–378. doi: 10.1007/s11205-016-1532-x, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stone A. A., Schwartz J. E., Broderick J. E., Deaton A. (2010). A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 9985–9990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003744107, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sunstein C. R. (2021). Some costs and benefits of cost-benefit analysis. Daedalus 150, 208–219. doi: 10.1162/daed_a_01868 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tiberius V. (2006). Well-being: psychological research for philosophers. Philos. Compass 1, 493–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-9991.2006.00038.x [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (823.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

One More Time, Does Money Buy Happiness?

- Published: 19 September 2023

- Volume 18 , pages 3089–3110, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- James Fisher ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9201-4204 1 &

- Michael Frechette ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8193-6796 2

2106 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This paper integrates multiple positions on the relationship between money and well-being, commonly referred to as happiness. An aggregation of prior work appears to suggest that money does buy happiness, but not directly. Although many personal and situational characteristics do influence the relationship between money and happiness, most are moderating factors, which would not necessarily rule out a direct link. Here, we discuss the cognitive and affective elements within the formation of happiness, which we propose play a series of mediating roles, first cognition, then affect, between money and happiness. The paper concludes with a discussion about how this proposal influences academic research and society as a whole.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price excludes VAT (USA) Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Functional and Dysfunctional Aspects of Happiness: Cognitive, Physiological, Behavioral, and Health Considerations

Happiness, Economics of

What We Have Learnt About Happiness

Materials and/or code availability.

There are no materials or code related to this manuscript.

Data Availability

This conceptual study collected no original data. Citations are given to the original sources when referencing data or results from prior studies.

“As far as I am aware, in every representative national survey ever done a significant positive bivariate relationship between happiness and income has been found.” (Easterlin 2001 , 468). Easterlin supports this assertion with references to Andrews 1996 , xi; Argyle 1999 , 356–57; and Diener 1984 , 553.