14 Experiments Gone Wrong

From psychological studies that would never pass ethical muster in the present day to disastrous new product launches, here are some experiments gone horrifically wrong, adapted from an episode of The List Show on YouTube.

1. Winthrop Kellogg's Ape Experiment

In the early 1930s, comparative psychologist Winthrop Kellogg and his wife welcomed a healthy baby boy they named Donald. The psychologist had grown interested in those stories of children who were raised feral—but he didn’t send Donald to be raised by wolves. He did the opposite: He managed to get his hands on a similar-aged baby chimp named Gua and raised her alongside Donald.

Gua initially did better than Donald in tests that included things like memory, scribbling, strength, dexterity, reflexes, problem-solving, climbing, language comprehension, and more. But she eventually plateaued, and it became evident that no amount of equal treatment was going to make her behave more like a human (for example, she was never going to be able to speak English).

But when the Kelloggs ended the experiment, they did so abruptly and without much explanation, which is contrary to the meticulous records they otherwise took throughout the course of the study. While Gua wasn’t showing any signs of picking up English, Donald had started to imitate the vocalizations of his sister from another species—so it’s not hard to speculate why the Kelloggs called it quits.

2. The Stanford Prison Experiment

You may have heard about the Stanford Prison Experiment, a social psychology study gone awry in 1971. The point of the experiment, which was funded by the U.S. Office of Naval Research, was to measure the effect of role-playing and social expectations. Lead researcher Philip Zimbardo had predicted that situations and circumstances dictate how a person acts, not their personalities.

To start, 24 young men were assigned the roles of prison guard or prison inmate, with some held back as alternates. Each was paid $15 per day for his participation in the study, which was supposed to last two weeks. The prisoners were “arrested,” taken to a fake prison in the basement of a school building, then made to wear a dress-like prison uniform with chains around their right ankle.

By the second day, the faux prisoners had revolted. Over the next few days, some of the prisoners were so traumatized that they were pulled out. The experiment was disbanded on day six, after an outside observer witnessed the upsetting events taking place and sounded the alarm.

Many modern-day researchers don’t believe the experiment can be replicated because it doesn’t meet today’s research ethics standards—namely, informed consent. After all, it’s hard to give fully informed consent when there’s no way to predict how events could unfold. Beyond that, some psychologists doubt the core findings of the experiment and claim that the cruelty didn’t emerge organically, but was instead influenced by Zimbardo nudging the experiment in that direction. Zimbardo, however, has defended his results and stated that these criticisms are misrepresenting his study and the experiences of the people in it.

3. Franz Reichelt's Aviator Suit

If there's anything to be said for Franz Reichelt, it's that he had supreme confidence in his own invention. In the early 1900s, Reichelt crafted a parachute from 320 square feet of fabric, all of which folded up into a wearable aviator suit . He had conducted several parachute tests using dummies, which all failed. He pinned the blame on the buildings, saying that they simply weren’t tall enough.

In 1912, Reichelt planned to test his latest version by flinging a dummy from the Eiffel Tower. But when he arrived at the famous landmark, the inventor surprised the waiting crowd by strapping on the parachute suit himself and taking the leap. The parachute didn’t open, however, and Reichelt became a victim of his own invention. (An autopsy reportedly determined that he died of a heart attack on the way down.)

4. McDonald's Bubblegum-Flavored Broccoli

In 2014, McDonald's concluded that they needed to offer more nutritious options for children—which led one mad scientist in Ronald’s test kitchen to come up with bubble gum-flavored broccoli. Luckily for all of us, this horrifying experiment never made it to a Happy Meal near you.

5. William Perkin's Mauve-lous Mistake

In 1856, chemist William Perkin was experimenting with ways to manufacture a synthetic version of quinine, a tonic water ingredient that also happens to treat malaria. At the time, dyes were only made from things like plant material and insects—but when Perkin was mixing up his latest quinine concoction, he accidentally produced an oily sludge that left a lovely shade of light purple residue. He had unwittingly discovered a way to produce mauve. The color was a smash hit, especially after Queen Victoria donned it for her daughter’s 1858 wedding.

6. The Michelson-Morley Experiment

Another happy failure is the Michelson-Morley Experiment. The experiment was supposed to detect ether , a substance that carried light waves, according to some scientists. The working theory at the time, in the late 1800s, was that ether was motionless, so the motion of Earth through space would alter the speed of light depending on what direction you were facing.

This was popularly known as “ether wind.” To test the ether wind theory, scientist Albert Michelson invented a device that could theoretically measure changes to the speed of light, thus detecting the supposed ether wind. The device was perfectly accurate, but it didn’t detect any changes in the speed of light. What Michelson and his collaborator Edward Morley discovered—or rather, didn’t discover—eventually led to Einstein’s theory of special relativity, and the realization that the speed of light is a universal constant, and there is no absolute space or absolute time.

7. The Cleveland Indians' 10-Cent Beer Night

In 1974, the Cleveland Indians tinkered with a new promotion to increase game attendance—giving fans the opportunity to purchase an unlimited amount of beer for 10 cents a cup , which wasn't the best idea. The game against the Texas Rangers was an eventful one: memorable events of the evening included a woman running into the Indians’ on-deck circle and flashing the umpire; a naked fan running onto the field and sliding into second base; and a father and son who ran onto the outfield and mooned the bleacher section.

Things took a violent turn when fans launched fireworks into the Rangers’ dugout, and the whole thing eventually turned into an all-out riot, fans against players on both teams. Players were hit with folding chairs, there were numerous fist fights, and some players were injured when they were pelted with rocks. After that, the Cleveland Indians kept 10 cent beer nights, but limited the promotion to two drinks per person.

8. Stubbins Ffirth's Yellow Fever Experiment

Stubbins Ffirth was a medical student who believed that yellow fever wasn’t contagious. To prove it, he tried some awful experiments on himself at the turn of the 19th century.

Ffirth cooked vomit from yellow fever patients on his stove and breathed in the vapors. He dropped the vomit into his eye, into an incision he had made in his left arm, and put drops of a patient’s blood serum into his left leg. Eventually, he was basically drinking shots of black vomit—straight. (He described the taste as “Very slightly acid.”)

How did he Ffirth manage to ingest all of this without falling ill? Well, we now know that Yellow Fever is spread by mosquitoes. So maybe Ffirth was vindicated? Is this just a disgusting experiment gone right ?

Not exactly. We also know now that yellow fever can be spread from human to human through direct bloodstream contact, and Ffirth was deliberately introducing samples to his bloodstream. So how’d he avoid contracting the virus? It’s been proposed that he may have had an immunity from an unrecorded bout of yellow fever earlier in life. Or maybe he just got extremely lucky and the samples he used were virus-free. Either way, if you’re chugging vomit and cutting open your arm to introduce a potentially lethal virus, it’s fair to say that something has gone wrong.

9. Biosphere 2

In the early ‘90s, eight scientists sealed themselves into a 3.14-acre structure in Arizona. The highly-publicized, $200-million experiment was known as Biosphere 2, and according to one of the scientists involved, its goals included “education, eco-technology development and learning how well our eco-laboratory worked.” But the scientists ran into a number of problems that required outside interference in order to continue the experiment, including a lack of sunlight that affected crops, a cockroach infestation, an injured crew member who had to temporarily leave for treatment, and insufficient oxygen.

In recent years, however, the success of Biosphere 2 has been re-evaluated , with some scientists believing that the base message—that humans can live in harmony with our biosphere—was a win in and of itself. And even if the vast investment was viewed as a mistake, the underlying idea remains solid: Similar experiments have been recently conducted to see if we can sustain human life on Mars.

10. The New Ball

Although basketball was originally played with soccer balls, a leather ball has been used since Spalding began manufacturing sport-specific balls in 1894. The basketball has been tweaked here and there over the years, but the modifications apparently went too far when the NBA experimented with a microfiber ball in 2006. “The New Ball,” as it was commonly known, was cheaper to make and was supposed to have the feel of a broken-in basketball right from the start.

Sounds good in theory, but players absolutely hated it. Shaquille O’Neal, LeBron James, and Dirk Nowitzki complained about the ball to the press. One issue was that the ball apparently became much more slippery than a traditional leather ball when it was wet, which happened frequently when sweaty basketball players were constantly handling it. Some players even reported that their hands were getting cut due to the increased friction of the microfiber surface.

Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban also commissioned a study from the physics department at the University of Texas at Austin, which found that the ball bounced 5 to 8 percent lower than a traditional leather ball and bounced up to 30 percent more erratically. Feeling deflated, the NBA officially announced they were pulling the ball from play on December 11, 2006—less than three months after its debut in a game.

11. Henry A. Murray's Psychological Experiments

It’s probably safe to say that an experiment falls into the “gone wrong” category when it may have been responsible for producing the Unabomber. As an undergrad at Harvard in the late 1950s and early '60s, Ted Kaczynski participated in a three-year-long study run by Henry A. Murray that explored the effects of stress on the human psyche. After being asked to submit an essay about their worldview and personal philosophies, Kaczynski and 21 other students were interrogated under bright lights, wired to electrodes, and completely torn down for their beliefs. The techniques were intended to “break” enemy agents during the Cold War—and the students were never completely informed about the nature of the study. In short, the man who would eventually kill three people and injure over 20 more with his homemade bombs was subjected to repeated psychological torture.

Kaczynski later described this as the worst experience of his life; still, we can’t assume the study was solely responsible for sending him down the destructive and murderous path he eventually followed. But at the very least, the study is now considered highly unethical and likely wouldn’t pass current ethics standards for research.

12. Wilhelm Reich's Cloudbusters

Psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich managed to draw a straight line from human orgasms to the weather to alien invasion. Influenced by Sigmund Freud ’s work on the human libido, Reich extended the concept to propose a kind of widespread energy he called orgone. To give you an idea of how scientifically sound Reich’s concept was, orgone has been compared to the Force in Star Wars . This energy was supposedly responsible for everything from the weather to why the sky is blue. Reich believed orgasms were a discharge of orgone, and that through the manipulation of this energy you could treat neuroses and even cancer.

As bizarre as this all sounds, Reich went even further in the late 1950s, when he became convinced that aliens were spraying the earth with a specific type of radiation to prevent us from using this powerful energy. In order to save the world, he and his son built Cloudbusters, a row of tubes attached to hoses immersed in water and aimed at the sky. The water, they believed, would absorb the radiation.

Did the experiment work? We don’t know for sure, but the FDA didn’t think so. They ordered Reich's various machines and apparatus destroyed, and had him jailed for trying to smuggle them out of state.

13. Duncan MacDougall's Soul Experiments

In 1901, Duncan MacDougall conducted experiments on extremely recently deceased people—and dogs—to see if their body weight changed immediately after death. A decrease in weight, he theorized, would be indicative of a physical soul leaving the body. To test this theory, he weighed six people before and after their deaths, and concluded that there was a weight difference anywhere from half to one and a half ounces (somewhere between one and three compact discs). He repeated the experiment on dogs and found no difference—and therefore, by MacDougall’s reasoning, dogs have no souls.

Other scientists have been critical of this experiment from day one, citing issues like small sample size and imprecise methods of measurement.

14. New Coke

April 23, 1985, was a day that will live in marketing infamy. And that’s how Coke describes the failed experiment that was New Coke . On that day, the Coca-Cola Company debuted a new version of their popular soft drink made from a new and supposedly improved formula. It was the first major change to the product in nearly a century, and it was one that was supported by overwhelmingly positive reviews in taste tests and focus groups.

But once New Coke actually hit the shelves, fans were absolutely outraged. While the taste tests accounted for the actual flavor of the new formula, it couldn’t account for the emotional ties consumers had to the brand history. Fans started hoarding “old” Coke, and complaints poured in to the tune of 1500 calls a day. CEO Roberto Goizueta even received a letter addressed to “Chief Dodo, The Coca-Cola Company.”

The message was received loud and clear. Coke announced the return of Old Coke in July, dubbing it Coca-Cola Classic—and they never experimented with the formula again. Or if they did, they kept it to themselves, and we’re none the wiser.

Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

These are science’s top 10 erroneous results.

Mistakes from the past demonstrate the reliability of science

By Tom Siegfried

Contributing Correspondent

November 10, 2020 at 6:00 am

Astronomers viewing supernova 1987A, pictured here, thought they saw a signal from a rapidly spinning neutron star too bizarre to comprehend. But the signal turned out to come from a quirk in the electronics of a camera used to aim the telescope.

Share this:

To err is human, which is really not a very good excuse.

And to err as a scientist is worse, of course, because depending on science is supposed to be the best way for people to make sure they’re right. But since scientists are human (most of them, anyway), even science is never free from error. In fact, mistakes are fairly common in science, and most scientists tell you they wouldn’t have it any other way. That’s because making mistakes is often the best path to progress. An erroneous experiment may inspire further experiments that not only correct the original error, but also identify new previously unsuspected truths.

Still, sometimes science’s errors can be rather embarrassing. Recently much hype accompanied a scientific report about the possibility of life on Venus. But instant replay review has now raised some serious concerns about that report’s conclusion. Evidence for the gas phosphine, a chemical that supposedly could be created only by life (either microbes or well-trained human chemists), has started to look a little shaky. ( See the story by well-trained Science News reporter Lisa Grossman.)

While the final verdict on phosphine remains to be rendered, it’s a good time to recall some of science’s other famous errors. We’re not talking about fraud here, or just bad ideas that were worth floating but flopped instead, or initial false positives due to statistical randomness. Rather, let’s just list the Top 10 erroneous scientific conclusions that got a lot of attention before ultimately getting refuted. (With one exception, there will be no names, for the purpose here is not to shame.)

10. A weird form of life

A report in 2010 claimed that a weird form of life incorporates arsenic in place of phosphorus in biological molecules. This one sounded rather suspicious, but the evidence, at first glance, looked pretty good. Not so good at second glance , though. And arsenic-based life never made it into the textbooks.

9. A weird form of water

In the 1960s, Soviet scientists contended that they had produced a new form of water. Ordinary water flushed through narrow tubes became denser and thicker, boiled at higher than normal temperatures and froze at much lower temperatures than usual. It seemed that the water molecules must have been coagulating in some way to produce “polywater.” By the end of the 1960s chemists around the world had begun vigorously pursuing polywater experiments. Soon those experiments showed that polywater’s properties came about from the presence of impurities in ordinary water.

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

8. Neutrinos, faster than light

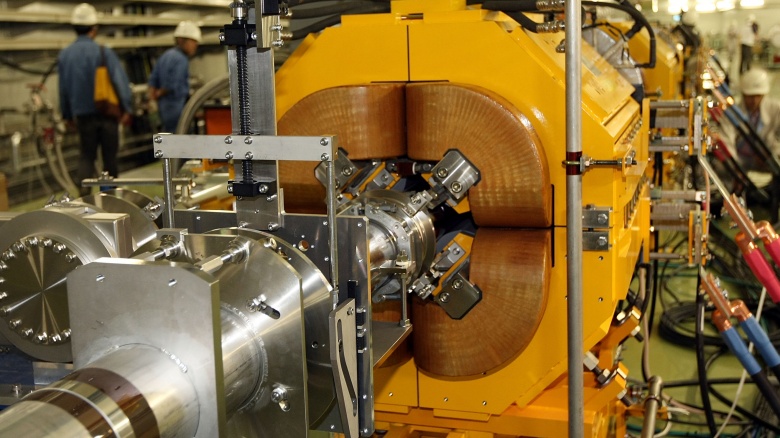

Neutrinos are weird little flyweight subatomic particles that zip through space faster than Usain Bolt on PEDs. But not as fast as scientists claimed in 2011, when they timed how long it took neutrinos to fly from the CERN atom smasher near Geneva to a detector in Italy. Initial reports found that the neutrinos arrived 60 nanoseconds sooner than a beam of light would. Faster-than-light neutrinos grabbed some headlines, evoked disbelief from most physicists and induced Einstein to turn over in his grave. But sanity was restored in 2012 , when the research team realized that a loose electrical cable knocked the experiment’s clocks out of sync, explaining the error.

7. Gravitational waves from the early universe

All space is pervaded by microwave radiation, the leftover glow from the Big Bang that kicked the universe into action 13.8 billion years ago. A popular theory explaining details of the early universe — called inflation — predicts the presence of blips in the microwave radiation caused by primordial gravitational waves from the earliest epochs of the universe.

In 2014, scientists reported finding precisely the signal expected, simultaneously verifying the existence of gravitational waves predicted by Einstein’s general theory of relativity and providing strong evidence favoring inflation. Suspiciously, though, the reported signal was much stronger than expected for most versions of inflation theory. Sure enough, the team’s analysis had not properly accounted for dust in space that skewed the data. Primordial gravitational waves remain undiscovered, though their more recent cousins, produced in cataclysmic events like black hole collisions, have been repeatedly detected in recent years .

6. A one-galaxy universe

In the early 20th century, astronomers vigorously disagreed on the distance from Earth of fuzzy cloudlike blobs shaped something like whirlpools (called spiral nebulae). Most astronomers believed the spiral nebulae resided within the Milky Way galaxy, at the time believed to comprise the entire universe. But a few experts insisted that the spirals were much more distant, themselves entire galaxies like the Milky Way, or “island universes.” Supposed evidence against the island universe idea came from measurements of internal motion in the spirals. It would be impossible to detect such motion if the spirals were actually way far away. But by 1924, Edwin Hubble established with certainty that at least sone of the spiral nebulae were in fact island universes, at vast distances from the Milky Way. Those measurements of internal motion were difficult to make — and they just turned out to be wrong.

5. A supernova’s superfast pulsar

Astronomers rejoiced in 1987 when a supernova appeared in the Large Magellanic Cloud, the closest such stellar explosion to Earth in centuries. Subsequent observations sought a signal from a pulsar, a spinning neutron star that should reside in the middle of the debris from some types of supernova explosions. But the possible pulsar remained hidden until January 1989, when a rapidly repeating radio signal indicated the presence of a superspinner left over from the supernova. It emitted radio beeps nearly 2,000 times a second — much faster than anybody expected (or could explain). But after one night of steady pulsing, the pulsar disappeared. Theorists raced to devise clever theories to explain the bizarre pulsar and what happened to it. Then in early 1990, telescope operators rotated a TV camera (used for guiding the telescope) back into service, and the signal showed up again — around a different supernova remnant. So the supposed signal was actually a quirk in the guide camera’s electronics — not a message from space.

4. A planet orbiting a pulsar

In 1991, astronomers reported the best case yet for the existence of a planet around a star other than the sun. In this case, the “star” was a pulsar, a spinning neutron star about 10,000 light-years from Earth. Variations in the timing of the pulsar’s radio pulses suggested the presence of a companion planet, orbiting its parent pulsar every six months. Soon, though, the astronomers realized that they had used an imprecise value for the pulsar’s position in the sky in such a way that the signal anomaly resulted not from a planet, but from the Earth’s motion around the sun.

3. Age of Earth

In the 1700s, French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffonestimated an Earth age of about 75,000 years, while acknowledging it might be much older. And geologists of the 19th century believe it to be older still — hundreds of millions of years or more — in order to account for the observation of layer after layer of Earth’s buried history. After 1860, Charles Darwin’s new theory of evolution also implied a very old Earth, to provide time for the diversity of species to evolve. But a supposedly definite ruling against such an old Earth came from a physicist who calculated how long it would take an originally molten planet to cool. He applied an age limit of about 100 million years, and later suggested that the actual age might even be much less than that. His calculations were in error, however — not because he was bad at math, but because he didn’t know about radioactivity.

Radioactive decay of elements in the Earth added a lot of heat into the mix, prolonging the cooling time. Eventually estimates of the Earth’s age based on rates of radioactive decay ( especially in meteorites that formed around the same time as the Earth) provided the correct current age estimate of 4.5 billion years or so.

2. Age of the universe

When astronomers first discovered that the universe was expanding, at the end of the 1920s, it was natural to ask how long it had been expanding. By measuring the current expansion rate and extrapolating backward, they found that the universe must be less than 2 billion years old. Yet radioactivity measurements had already established the Earth to be much older, and it was very doubtful (as in impossibly ridiculous) that the universe could be younger than the Earth. Those early calculations of the universe’s expansion, however, had been based on distance measurements relying on Cepheid variable stars.

Astronomers calculated the Cepheids’ distances based on how rapidly their brightness fluctuated, which in turn depended on their intrinsic brightness. Comparing intrinsic brightness to apparent brightness provided a Cepheid’s distance, just as you can gauge the distance of a lightbulb if you know its wattage (oh yes, and what kind of lightbulb it is). It turned out, though, that just like lightbulbs, there is more than one kind of Cepheid variable , contaminating the expansion rate calculations. Nowadays converging methods give an age of the universe of 13.8 billion years, making the Earth a relative newcomer to the cosmos.

1. Earth in the middle

OK, we’re going to name and blame Aristotle for this one. He wasn’t the first to say that the Earth occupies the center of the universe, but he was the most dogmatic about it, and believed he had established it to be incontrovertibly true — by using logic. He insisted that the Earth must be in the middle because earth (the element) always sought to move toward its “natural place,” the center of the cosmos. Even though Aristotle invented formal logic, he apparently did not notice a certain amount of circularity in his argument. It took a while, but in 1543 Copernicus made a strong case for Aristotle being mistaken. And then in 1610 Galileo’s observation that Venus went through a full set of phases sealed the case for a sun-centered solar system.

Now, it would be nice if there were a lesson in this list of errors that might help scientists do better in the future. But the whole history of science shows that such errors are actually unavoidable. There is a lesson, though, based on what the mistakes on this list have in common: They’re all on a list of errors now known to be errors. Science, unlike certain political philosophies and personality cults, corrects its mistakes. That’s the lesson, and that’s why respecting science is so important to avoiding errors in other realms of life.

More Stories from Science News on Science & Society

Here’s how long it would take 100 worms to eat the plastic in one face mask

A new biography of Benjamin Franklin puts science at the forefront

This ‘hidden figure’ of entomology fought for civil rights

From electric cars to wildfires, how Trump may affect climate actions

Dengue is classified as an urban disease. Mosquitoes don’t care

Researchers seek, and find, a magical illusion for the ears

Fire-prone neighborhoods on the fringes of nature are rapidly expanding

Exploiting a genetic quirk in potatoes may cut fertilizer needs

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

20 of the Greatest Blunders in Science in the Last 20 Years

What were they thinking.

In the last two decades, glorious scientific and technical achievements have altered our lives forever. Try, for example, to imagine the world without the existence of those two little words personal and computer. But there have also been — how can this be put delicately?— blunders.

Some were errors in concept: Bad science chasing a bad idea. Some were errors in execution: This would have worked so well if only it hadn't blown up. Others were cases of deliberate fraud, out-and-out hoaxes, or just dopey moments that made us laugh. Perhaps Albert Einstein said it best: "Two things are infinite: the universe and human stupidity, and I'm not sure about the universe."

Surreal in its beauty, a plume of white smoke ushered in the end of America's romance with space travel after the shuttle Challenger blew up 73 seconds into its scheduled six-day flight on January 28, 1986, at 11:39:13 a.m.

The rocket was traveling at Mach 1.92 at an altitude of 46,000 feet as it incinerated all seven astronauts aboard. According to the presidential commission that investigated the accident, the explosion was caused by the failure of an O-ring seal in the joint between the two lower segments of the right-hand solid-rocket booster.

This failure permitted a jet of white-hot gases to ignite the liquid fuel of the external tank. The O-ring was known to fail in cold temperatures, but the launch had been delayed five times.

Darsee and Slutsky and Fraud, Oh My!

Following the "greed is good" mantra of the 1980s, some scientists could not resist shortcuts. "The psychological profile of these people is interesting," says Mario Biagioli, a professor of the history of science at Harvard University. "You usually get B-plus, A-minus scientists who get into hyperproduction mode."

Take, for example, former Harvard researcher John Darsee. In 1981 he was found to be faking data in a heart study. Eventually investigators at the National Institutes of Health discovered that data for most of his 100 published studies had been fabricated.

Or take the case of cardiac-radiology specialist Robert Slutsky, who in 1985 resigned from the University of California at San Diego School of Medicine after colleagues began to wonder how he turned out a new research article every 10 days. University investigators concluded he had altered data and lied about the methods he used. To establish verisimilitude, Slutsky often persuaded scientists more prominent than he to put their names on his articles.

The Debendox Debacle

William McBride, an Australian obstetrician, was hailed as a whistle-blowing visionary in 1961 when he sounded a warning about the dangers of thalidomide, a sedative prescribed for anxiety and morning sickness. In a letter to the journal The Lancet , McBride suggested that the drug was causing infants to be born with severe limb deformities.

Although McBride's hypothesis was based on limited anecdotal observations, subsequent studies proved him right. Thalidomide was removed from the market, and the drug became almost synonymous with pharmaceutical malfeasance. Two decades later, in 1982, McBride published a report about a morning-sickness drug called Debendox that, he claimed, clearly caused birth defects in rabbits. Merrell Dow took the drug off the market amid an avalanche of lawsuits.

But there was a problem. McBride had altered data in research carried out by assistants. The results showed Debendox had no ill effects. After years of investigation, McBride was found guilty of scientific fraud in 1993 by a medical tribunal.

Nuclear Winter of Our Discontent

In 1983, astronomer Carl Sagan coauthored an article in Science that shook the world: "Nuclear Winter: Global Consequences of Multiple Nuclear Explosions" warned that nuclear war could send a giant cloud of dust into the atmosphere that would cover the globe, blocking sunlight and invoking a climatic change similar to that which might have ended the existence of dinosaurs. Skeptical atmospheric scientists argued that Sagan's model ignored a variety of factors, including the fact that the dust would have to reach the highest levels of the atmosphere not to be dissipated by rainfall.

In a 1990 article in Science, Sagan and his original coauthors admitted that their initial temperature estimates were wrong. They concluded that an all-out nuclear war could reduce average temperatures at most by 36 degrees Fahrenheit in northern climes. The chilling effect, in other words, would be more of a nuclear autumn.

Piltdown Chicken

The finding was initially trumpeted as the missing link that proved birds evolved from dinosaurs. In 1999 a fossil smuggled out of China allegedly showing a dinosaur with birdlike plumage was displayed triumphantly at the National Geographic Society and written up in the society's November magazine.

Paleontologists were abuzz. Unfortunately, like the hominid skull with an ape jaw discovered in the Piltdown quarries of England in 1912, the whole thing turned out to be a hoax. The fossil apparently was the flight of fancy of a Chinese farmer who had rigged together bird bits and a meat-eater's tail.

Statistics for Dummies

Shocking factoids based on half-baked interpretations of scientific data have been foisted on the public at an alarming rate during the past 20 years. Take the "spinsters beware" theme that gained currency in 1986. Summarizing a study on women and marriage by two Yale sociologists and a Harvard economist, several news agencies reported that single women at 35 had only a 5 percent chance of ever marrying, and unmarried women at 40 were "more likely to be killed by a terrorist."

Never mind the fact that in analyzing data from the 70,000 households the authors of the original study had not looked into what percentage of the over-30 women had made a conscious choice to put off marriage. Indeed, U.S. Census Bureau statistician Jeanne Moorman's follow-up projections indicate that of unmarried women ages 30 to 34, 54 percent will marry; of those ages 35 to 39, 37 percent will marry; and of those ages 40 to 44, 24 percent will marry.

Very Cold Fusion

At the University of Utah in 1989, chemists Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann announced that the world's energy problems had been solved. They claimed to have created nuclear fusion on a tabletop by electrolyzing deuterium oxide — heavy water — using electrodes made of palladium and platinum.

Deuterium is a naturally occurring stable isotope of hydrogen; its nucleus contains a neutron in addition to the single proton found in the nucleus of ordinary hydrogen. According to the chemists, the deuterium nuclei were squeezed so closely together in the palladium cathode that they fused, releasing energy.

As Robert Park, professor of physics at the University of Maryland and author of Voodoo Science puts it, "Basically if what Fleischmann and Pons said was true, they had duplicated the source of the sun's energy in a test tube."

The problem is, no other scientists have been able to reproduce their results — and not for lack of trying. "There's always some guy willing to say, 'OK, we found something that works, but it only works once in a while,' or 'We're not going to show it to you, because we're worried you'll steal our patent rights,'" says Marc Abrahams, editor of Annals of Improbable Research.

April 26, 1986, was the day Soviet nuclear experts learned the true meaning of the word oops. During a test of one of Chernobyl's four reactors, they turned off the backup cooling system and used only eight boron-carbide rods to control the rate of fission instead of the 15 rods required as standard operating procedure.

A runaway chain reaction blew the steel and concrete lid off the reactor and created a fireball, releasing 100 times more radiation than did the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs combined. Some 4,300 people eventually died as a result, and more than 70,000 were permanently disabled.

Currents That Don't Kill

The Clinton administration estimates that American taxpayers have paid $25 billion to determine that power lines don't do anything more deadly than deliver power. In 1989, Paul Brodeur published a series of articles in The New Yorker raising the possibility of a link between electromagnetic fields and cancer. Eight years later, after several enormous epidemiological studies in Canada, Britain, and the United States, the danger was completely discounted.

"All known cancer-inducing agents act by breaking chemical bonds in DNA," says Robert Park. "The amount of photon energy it takes is an ultraviolet wavelength. So any wavelength that is longer cannot break chemical bonds. Visible light does not cause cancer. Infrared light is still longer, radio waves longer still. Power-line fields are preposterous. The wavelength is in miles."

Mars Meltdowns

The "better, faster, cheaper" mantra adopted by NASA in 1992 might be reinterpreted today as "you get what you pay for." In September 1999, the $125-million Mars Climate Orbiter plunged to oblivion near Mars. NASA officials were using the metric newton to guide the spacecraft.

That was unfortunate, because Lockheed-Martin engineered the Orbiter to be guided in the English units of poundals. In December, the $185-million Mars Polar Lander went AWOL, and repeated efforts to contact it by space radio antennas failed. Officials now speculate that a signaling problem in the landing legs — caused by one line of missing computer code — doomed the Lander.

Rock of Life

In 1996, scientists at NASA declared that a 6.3-ounce rock, broken off from a Mars meteorite discovered in Antarctica in 1984, contained flecks of chemical compounds — polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, magnetite, and iron sulfide — that suggested the existence of bacteria on the Red Planet 3.6 billion years ago. "August 7, 1996, could go down as one of the most important dates in human history," intoned one newspaper report. But within two years the theory began to crack.

Traces of amino acids found in the rock, crucial to life, were also found in the surrounding Antarctic ice. More damning, other non-Martian rocks — rocks from the moon, where it is clear life does not exist — showed the same "evidence" of life. By November 1998 an article in Science declared "most researchers agree that the case for life on Mars is shakier than ever."

Sometimes mistakes that were made decades ago take a while to make the force of their foolishness felt. Consider the case of killer bees. In the 1950s, Brazilian geneticists crossbred mild-mannered European honeybees with their more aggressive, territorial cousins from Africa, reasoning that the Africanized bees would be better suited than their European counterparts to warmer South American climes.

They were too right. Before the aggression could be bred out of the resulting cross, the buggers got away, and some immediately headed north. In 1990 the first Africanized honeybees were discovered in Texas. Since that time they've gradually spread to New Mexico, Arizona, California, and in 1999, to Nevada.

Here They Come to Save the Day

Indeed, antibiotics have been the Mighty Mouse of medicine. Since the discovery of penicillin in 1928, it seemed there were few bacteria that antibiotics couldn't destroy handily. At the turn of the last century, the average life expectancy was 47. Thanks partly to a decline in bacterial diseases like tuberculosis, dysentery, and gonorrhea, life expectancy in the United States has risen to 76 today.

Unfortunately, doctors did not take seriously the consequences of promiscuous antibiotic use. Physicians have long been generous in prescribing antibiotics for minor ailments, even for viral infections like the common cold. Moreover, even when antibiotics were warranted, patients were not sufficiently warned about the dangers of not taking the drugs for the full course of treatment. When the symptoms of their infection abated, patients often threw away their pills, allowing the bacteria that had not been killed off to mutate.

Now there are whole categories of antibiotics that no longer work. And there are some potentially deadly bacterial diseases, including tuberculosis, that can only be beaten by one or two of the strongest, most expensive antibiotics.

The Sky Is Falling Again

Um, never mind. On March 12, 1998, on the front page of The New York Times , a headline read: "Asteroid Is Expected to Make a Pass Close to Earth in 2028."

Brian G. Marsden, director of the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, predicted that on October 26, 2028, an asteroid about a mile in diameter would come within 30,000 miles of Earth. That's within spitting distance, spacewise, which evoked comparisons to the asteroid that crashed on the Yucatàn peninsula 65 million years ago, allegedly wiping out all the dinosaurs.

"When you first discover a comet, or any kind of body, you start measuring its position," notes Robert Park. "From that you extract its trajectory. The more measurements you make, the more accurate your trajectory gets."

Marsden issued his warnings based on very early trajectory measurements. Now he anticipates the asteroid will pass Earth at a safe distance of 600,000 miles.

Evolution? What's That?

In 1995, it became official: Colorado students would not be tested on evolution, Charles Darwin's theory that, through an endless series of genetic mutations, we all developed from single-celled organisms. "I believe in divine creation," said Clair Orr, Colorado's chairman of the state's board of education.

Colorado is not alone. Kansas removed evolutionary theory from its tests in 1999. Mississippi and Tennessee do not teach the subject at all, and curricula in Florida and South Carolina touch on it only lightly.

Given the trend of treating all theories of how we got here as equal, Marc Abrahams, of Annals of Improbable Research, has a suggestion: Why not teach the theory of Chonosuke Okamura, a Japanese paleontologist who became convinced that patterns of water seepage in rocks were "mini-fossils" and that life was descended from mini-horses, mini-cows, and mini-dragons. "It's kind of like forming an evolutionary theory out of cloud formations," says Abrahams.

Fen-phen Fiasco

In the early 1990s Michael Weintraub, a researcher at the University of Rochester, concluded that a combination of two nonaddictive drugs that had been around for years — phentermine, a stimulant, and fenfluramine, an appetite suppressant — could be used for the long-term control of obesity. The fen-phen diet craze was born.

Physicians began giving the drug combination off-label to patients who wanted to lose as little as 10 to 15 pounds. In the meantime, an August 1996 report in The New England Journal of Medicine linked the use of fen-phen for more than three months to a 23-fold increased risk of developing primary pulmonary hypertension, a fatal lung disorder.

Subsequent studies revealed that prolonged use of fenfluramine could cause heart-valve defects. By September 1997, the Food and Drug Administration signaled the demise of fen-phen by ordering that fenfluramine be taken off the market. It is estimated that between 1.2 million and 4.7 million Americans were exposed to the drug combination.

To Be or Not to Be, Thanks to MTBE

It was intended to solve a pollution problem. Instead, it may be the cause of one of the most serious pollution problems of our time. MTBE, or methyl tertiary butyl ether, is a gasoline additive that came into use in the late 1970s during the phaseout of alkyl lead additives. It helps gasoline burn more efficiently and cuts down on air pollutants.

It also happens to be highly water-soluble and has a nasty tendency to leak from underground storage tanks at gas stations. In California, MTBE contamination has forced water suppliers to shut down wells in many counties.

A recent study by the U.S. Geological Survey found MTBE in 14 percent of all urban drinking water wells it sampled. In March 1999, the Clinton administration announced a ban on the additive. Meanwhile, there appears to be no cost-effective way to remove it from drinking water.

Earth to Iridium

The award for "Most Expensive Piece of Immediately Obsolete Technology" goes to Iridium, a communications company that 10 years ago promised crystal-clear cellular phone service anywhere on the planet. Sixty-six satellites were launched at a cost of $5 billion.

"The phones were bulky. They cost $3,000. A call cost several dollars per minute, and the system didn't work indoors," says Richard Kadrey, a founder of Dead Media Project, a Web-site collection of failed media and technology. "Most people simply don't need to call Dakar at a moment's notice. In fact, the number of people who do is so small that it is probably dwarfed by the number of people who really need to talk to aliens."

In 1999, Iridium took its place among the 20 largest bankruptcies in history.

Chest Say No to Silicone Implants

Pamela Anderson had them taken out. So did Jenny Jones. They needn't have bothered, according to an independent panel of medical experts. Never mind that lawsuits over the implants bankrupted Dow Corning, a multibillion-dollar company. The medical panel reported in 1998 that there is no greater incidence of immune-system abnormalities among women with breast implants than there is in the general population.

In the end the science didn't fail us; the lawyers did.

It all got fixed before it could happen, but at a cost of $100 billion. Thanks to purposeful programming, computers were likely to read the year code "00" as 1900 instead of 2000. So we were treated to an entire year of talking heads ranting on about doomsday scenarios, including a world where airplanes would drop out of the sky and banks would register your portfolio value as zero. And some people don't have to buy canned goods for at least a year. All we can say is: Thank you, Bill Gates.

More Resources: Invasive species bugging you? See a report by the U.S. Geological Survey's Biological Resources Division at biology.usgs.gov/ s+t/ SNT/ noframe/ ns112.htm . For further information on the Chernobyl disaster, visit the Uranium Institute. The official NASA site dedicated to the Challenger disaster is www.hq.nasa.gov/ office/pao/ History/sts51l.html .

- medical technology

Already a subscriber?

Register or Log In

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Advertisement

10 Outrageous Experiments Conducted on Humans

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

Prisoners, the disabled, the physically and mentally sick, the poor -- these are all groups once considered fair game to use as subjects in your research experiments. And if you didn't want to get permission, you didn't have to, and many doctors and researchers conducted their experiments on people who were unwilling to participate or who were unknowingly participating.

Forty years ago the U.S. Congress changed the rules; informed consent is now required for any government-funded medical study involving human subjects. But before 1974 the ethics involved in using humans in research experiments was a little, let's say, loose. And the exploitation and abuse of human subjects was often alarming. We begin our list with one of the most famous instances of exploitation, a study that eventually helped change the public view about the lack of consent in the name of scientific advancements.

- Tuskegee Syphilis Study

- The Nazi Medical Experiments

- Watson's 'Little Albert' Experiment

- The Monster Study of 1939

- Stateville Penitentiary Malaria Study

- The Aversion Project in South Africa

- Milgram Shock Experiments

- CIA Mind-Control Experiments (Project MK-Ultra)

- The Human Vivisections of Herophilus

10: Tuskegee Syphilis Study

Syphilis was a major public health problem in the 1920s, and in 1928 the Julius Rosenwald Fund, a charity organization, launched a public healthcare project for blacks in the American rural south. Sounds good, right? It was, until the Great Depression rocked the U.S. in 1929 and the project lost its funding. Changes were made to the program; instead of treating health problems in underserved areas, in 1932 poor black men living in Macon County, Alabama, were instead enrolled in a program to treat what they were told was their "bad blood" (a term that, at the time, was used in reference to everything from anemia to fatigue to syphilis). They were given free medical care, as well as food and other amenities such as burial insurance, for participating in the study. But they didn't know it was all a sham. The men in the study weren't told that they were recruited for the program because they were actually suffering from the sexually transmitted disease syphilis, nor were they told they were taking part in a government experiment studying untreated syphilis, the "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male." That's right: untreated.

Despite thinking they were receiving medical care, subjects were never actually properly treated for the disease. This went on even after penicillin hit the scene and became the go-to treatment for the infection in 1945, and after Rapid Treatment Centers were established in 1947. Despite concerns raised about the ethics of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study as early as 1936, the study didn't actually end until 1972 after the media reported on the multi-decade experiment and there was subsequent public outrage.

9: The Nazi Medical Experiments

During WWII, the Nazis performed medical experiments on adults and children imprisoned in the Dachau, Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen concentration camps. The accounts of abuse, mutilation, starvation, and torture reads like a grisly compilation of all nine circles of hell. Prisoners in these death camps were subjected to heinous crimes under the guise of military advancement, medical and pharmaceutical advancement, and racial and population advancement.

Jews were subjected to experiments intended to benefit the military, including hypothermia studies where prisoners were immersed in ice water in an effort to ascertain how long a downed pilot could survive in similar conditions. Some victims were only allowed sea water, a study of how long pilots could survive at sea; these subjects, not surprisingly, died of dehydration. Victims were also exposed to high altitude in decompression chambers -- often followed with brain dissection on the living -- to study high-altitude sickness and how pilots would be affected by atmospheric pressure changes.

Effectively treating war injuries was also a concern for the Nazis, and pharmaceutical testing went on in these camps. Sulfanilamide was tested as a new treatment for war wounds. Victims were inflicted with wounds that were then intentionally infected. Infections and poisonings were also studied on human subjects. Tuberculosis (TB) was injected into prisoners in an effort to better understand how to immunize against the infection. Experiments with poison, to determine how fast subjects would die, were also on the agenda.

The Nazis also performed genetic and racially-motivated sterilizations, artificial inseminations, and also conducted experiments on twins and people of short stature.

8: Watson's 'Little Albert' Experiment

In 1920 John Watson, along with graduate student Rosalie Rayner, conducted an emotional-conditioning experiment on a nine-month-old baby -- whom they nicknamed "Albert B" -- at Johns Hopkins University in an effort to prove their theory that we're all born as blank slates that can be shaped. The child's mother, a wet nurse who worked at the hospital, was paid one dollar for allowing her son to take part.

The "Little Albert" experiment went like this: Researchers first introduced the baby to a small, furry white rat, of which he initially had no fear . (According to reports, he didn't really show much interest at all). Then they re-introduced him to the rat while a loud sound rang out. Over and over, "Albert" was exposed to the rat and startling noises until he became frightened any time he saw any small, furry animal (rats, for sure, but also dogs and monkeys) regardless of noise.

Who exactly "Albert" was remained unknown until 2010, when his identity was revealed to be Douglas Merritte. Merritte, it turns out, wasn't a healthy subject: He showed signs of behavioral and neurological impairment, never learned to talk or walk, and only lived to age six, dying from hydrocephalus (water on the brain). He also suffered from a bacterial meningitis infection he may have acquired accidentally during treatments for his hydrocephalus, or, as some theorize, may have been -- horrifyingly -- intentionally infected as part of another experiment.

In the end, Merritte was never deconditioned, and because he died at such a young age no one knows if he continued to fear small furry things post-experiment.

7: The Monster Study of 1939

Today we understand that stuttering has many possible causes. It may run in some families, an inherited genetic quirk of the language center of the brain. It may also occur because of a brain injury, including stroke or other trauma. Some young children stutter when they're learning to talk, but outgrow the problem. In some rare instances, it may be a side effect of emotional trauma. But you know what it's not caused by? Criticism.

In 1939 Mary Tudor, a graduate student at the University of Iowa, and her faculty advisor, speech expert Wendell Johnson, set out to prove stuttering could be taught through negative reinforcement -- that it's learned behavior. Over four months, 22 orphaned children were told they would be receiving speech therapy, but in reality they became subjects in a stuttering experiment; only about half were actually stutterers, and none received speech therapy.

During the experiment the children were split into four groups:

- Half of the stutterers were given negative feedback.

- The other half of stutterers were given positive feedback.

- Half of the non-stuttering group were all told they were beginning to stutterer and were criticized.

- The other half of non-stutterers were praised.

The only significant impact the experiment had was on that third group; these kids, despite never actually developing a stutter, began to change their behavior, exhibiting low self-esteem and adopting the self-conscious behaviors associated with stutterers. And those who did stutter didn't cease doing so regardless of the feedback they received.

6: Stateville Penitentiary Malaria Study

It's estimated that between 60 to 65 percent of American soldiers stationed in the South Pacific during WWII suffered from a malarial infection at some point during their service. For some units the infection proved to be more deadly than the enemy forces were, so finding an effective treatment was a high priority [source: Army Heritage Center Foundation]. Safe anti-malarial drugs were seen as essential to winning the war.

Beginning in 1944 and spanning over the course of two years, more than 400 prisoners at the Stateville Penitentiary in Illinois were subjects in an experiment aimed at finding an effective drug against malaria . Prisoners taking part in the experiment were infected with malaria, and then treated with experimental anti-malarial treatments. The experiment didn't have a hidden agenda, and its unethical methodology didn't seem to bother the American public, who were united in winning WWII and eager to bring the troops home — safe and healthy. The intent of the experiments wasn't hidden from the subjects, who were at the time praised for their patriotism and in many instances given shorter prison sentences in return for their participation.

5: The Aversion Project in South Africa

If you were living during the apartheid era in South Africa, you lived under state-regulated racial segregation. If that itself wasn't difficult enough, the state also controlled your sexuality.

The South African government upheld strict anti-homosexual laws. If you were gay you were considered a deviant — and your homosexuality was also considered a disease that could be treated. Even after homosexuality ceased to be considered a mental illness and aversion therapy as a way to cure it debunked, psychiatrists and Army medical professionals in the South African Defense Force (SADF) continued to believe the outdated theories and treatments. In particular, aversion therapy techniques were used on prisoners and on South Africans who were forced to join the military under the conscription laws of the time.

At Ward 22 at 1 Military hospital in Voortrekkerhoogte, Pretoria, between 1969 and 1987 attempts were made to "cure" perceived deviants. Homosexuals, gay men and lesbians were drugged and subjected to electroconvulsive behavior therapy while shown aversion stimuli (same-sex erotic photos), followed by erotic photos of the opposite sex after the electric shock. When the technique didn't work (and it absolutely didn't), victims were then treated with hormone therapy, which in some cases included chemical castration. In addition, an estimated 900 men and women also underwent gender reassignment surgery when subsequent efforts to "reorient" them failed — most without consent, and some left unfinished [source: Kaplan ].

4: Milgram Shock Experiments

Ghostbuster Peter Venkman, who is seen in the fictional film conducting ESP/electro-shock experiments on college students, was likely inspired by social psychologist Stanley Milgram's famous series of shock experiments conducted in the early 1960s. During Milgram's experiments "teachers" — Americans recruited for a Yale study they thought was about memory and learning — were told to read lists of words to "learners" (actors, although the teachers didn't know that). Each person in the teacher role was instructed to press a lever that would deliver a shock to their "learner" every time he made a mistake on word-matching quizzes. Teachers believed the voltage of shocks increased with each mistake, and ranged from 15 to 450 possible volts; roughly two-thirds of teachers shocked learners to the highest voltage , continuing to deliver jolts at the instruction of the experimenter.

In reality, this wasn't an experiment about memory and learning; rather, it was about how obedient we are to authority. No shocks were actually given.

Today, Milgram's shock experiments continue to be controversial; while they're criticized for their lack of realism, others point to the results as important to how humans behave when under duress. In 2010 the results of Milgram's study were repeated — with about 70 percent of teachers obediently administering what they believed to be the highest voltage shocks to their learners.

3: CIA Mind-Control Experiments (Project MK-Ultra)

If you're familiar with "Men Who Stare at Goats" or "The Manchurian Candidate" then you know: There was a period in the CIA's history when they performed covert mind-control experiments. If you thought it was fiction, it wasn't.

During the Cold War the CIA started researching ways they could turn Americans into CIA-controlled "superagents," people who could carry out assassinations and who wouldn't be affected by enemy interrogations. Under what was known as the MK-ULTRA project, CIA researchers experimented on unsuspecting American (and Canadian) citizens by slipping them psychedelic drugs, including LSD , PCP and barbiturates, as well as additional — and additionally illegal — methods such as hypnosis, and, possibly, chemical, biological, and radiological agents. Universities participated, mostly as a delivery system, also without their knowledge. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs estimates 7,000 soldiers were also involved in the research, without their consent.

The project endured for more than 20 years, during which the agency spent about $20 million. There was one death tied to the project, although more were suspected; tin 1973 the CIA destroyed what records were kept.

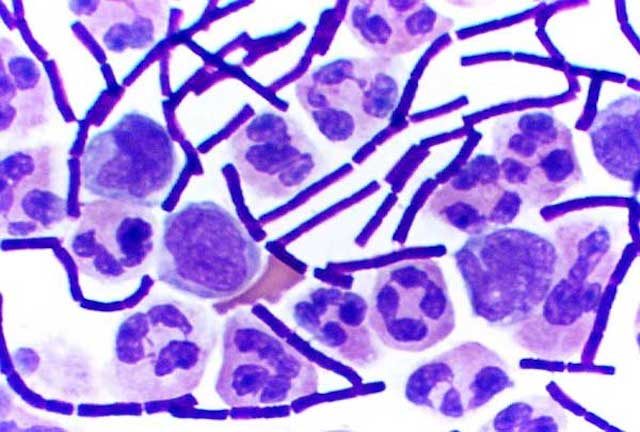

2: Unit 731

Using biological warfare was banned by the Geneva Protocol in 1925, but Japan rejected the ban. If germ warfare was effective enough to be banned, it must work, military leaders believed. Unit 731 , a secret unit in a secret facility — publicly known as the Epidemic Prevention and Water Supply Unit — was established in Japanese-controlled Manchuria, where by the mid-1930s Japan began experimenting with pathogenic and chemical warfare and testing on human subjects. There, military physicians and officers intentionally exposed victims to infectious diseases including anthrax , bubonic plague, cholera, syphilis, typhus and other pathogens, in an effort to understand how they affected the body and how they could be used in bombs and attacks in WWII.

In addition to working with pathogens, Unit 731 conducted experiments on people, including — but certainly not limited to — dissections and vivisections on living humans, all without anesthesia (the experimenters believed using it would skew the results of the research).

Many of the subjects were Chinese civilians and prisoners of war, but also included Russian and American victims among others — basically, anyone who wasn't Japanese was a potential subject. Today it's estimated that about 100,000 people were victims within the facility, but when you include the germ warfare field experiments (such as reports of Japanese planes dropping plague-infected fleas over Chinese villages and poisoning wells with cholera) the death toll climbs to estimates closer to 250,000, maybe more.

Believe it or not, after WWII the U.S. granted immunity to those involved in these war crimes committed at Unit 731 as part of an information exchange agreement — and until the 1980s, the Japanese government refused to admit any of this even happened.

1: The Human Vivisections of Herophilus

Ancient physician Herophilus is considered the father of anatomy. And while he made significant discoveries during his practice, it's how he learned about internal workings of the human body that lands him on this list.

Herophilus practiced medicine in Alexandria, Egypt, and during the reign of the first two Ptolemaio Pharoahs was allowed, at least for about 30 to 40 years, to dissect human bodies, which he did, publicly, along with contemporary Greek physician and anatomist Erasistratus. Under Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II, criminals could be sentenced to dissection and vivisection as punishment, and it's said the father of anatomy not only dissected the dead but also performed vivisection on an estimated 600 living prisoners [source: Elhadi ].

Herophilus made great strides in the study of human anatomy — especially the brain , eyes, liver, circulatory system, nervous system and reproductive system, during a time in history when dissecting human cadavers was considered an act of desecration of the body (there were no autopsies conducted on the dead, although mummification was popular in Egypt at the time). And, like today, performing vivisection on living bodies was considered butchery.

Frequently Asked Questions

How have these experiments influenced current ethical standards in research, what protections are in place today to prevent similar unethical research on humans, lots more information, author's note.

There is no denying that involving living, breathing humans in medical studies have produced some invaluable results, but there's that one medical saying most of us know, even if we're not in a medical field: first do no harm (or, if you're fancy, primum non nocere).

Related Articles

- What will medicine consider unethical in 100 years?

- How Human Experimentation Works

- Top 5 Crazy Government Experiments

- 10 Cover-ups That Just Made Things Worse

- 10 Really Smart People Who Did Really Dumb Things

- How Scientific Peer Review Works

More Great Links

- Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1948: "Procedures Used at Stateville Penitentiary for the Testing of Potential Antimalarial Agents"

- Stanley Milgram: "Behavioral Study of Obedience"

- Alving, Alf S. "Procedures Used At Stateville Penitentiary For The Testing Of Potential Antimalarial Agents." Journal of Clinical Investigation. Vol. 27, No. 3 (part 2). Pages 2-5. May 1948. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.jci.org/articles/view/101956

- American Heritage Center Foundation. "Education Materials Index: Malaria in World War II." (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.armyheritage.org/education-and-programs/educational-resources/education-materials-index/50-information/soldier-stories/182-malaria-in-world-war-ii

- Bartlett, Tom. "A New Twist in the Sad Saga of Little Albert." The Chronicle of Higher Education." Jan. 25, 2012. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://chronicle.com/blogs/percolator/a-new-twist-in-the-sad-saga-of-little-albert/28423

- Blass, Thomas. "The Man Who Shocked The World." Psychology Today. June 13, 2012. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/200203/the-man-who-shocked-the-world

- Brick, Neil. "Mind Control Documents & Links." Stop Mind Control and Ritual Abuse Today (S.M.A.R.T.). (Aug. 10, 2014) https://ritualabuse.us/mindcontrol/mc-documents-links/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee: The Tuskegee Timeline." Dec. 10, 2013. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm

- Cohen, Baruch. "The Ethics Of Using Medical Data From Nazi Experiments." Jlaw.com - Jewish Law Blog.(Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.jlaw.com/Articles/NaziMedEx.html

- Collins, Dan. "'Monster Study' Still Stings." CBS News. Aug. 6, 2003. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.cbsnews.com/news/monster-study-still-stings/

- Comfort, Nathaniel. "The prisoner as model organism: malaria research at Stateville Penitentiary." Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences." Vol. 40, no. 3. Pages 190-203. September 2009. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2789481/

- DeAngelis, T. "'Little Albert' regains his identity." Monitor on Psychology. Vol. 41, no. Page 10. 2010. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.apa.org/monitor/2010/01/little-albert.aspx

- Elhadi, Ali M. "The Journey of Discovering Skull Base Anatomy in Ancient Egypt and the Special Influence of Alexandria." Neurosurgical Focus. Vol. 33, No. 2. 2012. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/769263_5

- Fridlund, Alan J. "Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child." History of Psychology. Vol. 15, No. 4. Pages 302-327. November 2013. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2012-01974-001/

- Harcourt, Bernard E. "Making Willing Bodies: Manufacturing Consent Among Prisoners and Soldiers, Creating Human Subjects, Patriots, and Everyday Citizens - The University of Chicago Malaria Experiments on Prisoners at Stateville Penitentiary." University of Chicago Law & Economics, Olin Working Paper No. 544; Public Law Working Paper No. 341. Feb. 6, 2011. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1758829

- Harris, Sheldon H. "Biological Experiments." Crimes of War Project. 2011. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.crimesofwar.org/a-z-guide/biological-experiments/

- Hornblum, Allen M. "They Were Cheap and Available: Prisoners as Research Subjects in Twentieth Century America." British Medical Journal. Vol. 315. Pages 1437-1441. 1997. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://gme.kaiserpapers.org/they-were-cheap-and-available.html

- Kaplan, Robert. "The Aversion Project -- Psychiatric Abuses In The South African Defence Force During The Apartheid Era." South African Medical Journal. Vol. 91, no. 3. Pages 216-217. March 2001. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://archive.samj.org.za/2001%20VOL%2091%20Jan-Dec/Articles/03%20March/1.5%20THE%20AVERSION%20PROJECT%20-%20PSYCHIATRIC%20ABUSES%20IN%20THE%20SOUTH%20AFRICAN%20DEFENCE%20FORCE%20DURING%20THE%20APART.pdf

- Kaplan, Robert M. "Treatment of homosexuality during apartheid." British Medical Journal. Vol. 329, no. 7480. Pages 1415-1416. Dec. 18, 2004. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC535952/

- Kaplan, Robert M. "Treatment of homosexuality in the South African Defence Force during the Apartheid years ." British Medical Journal. February 20, 2004. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/10/30/treatment-homosexuality-south-african-defence-force-during-apartheid-years

- Keen, Judy. "Legal battle ends over stuttering experiment." USA Today. Aug. 27, 2007. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-08-26-stuttering_N.htm

- Kristof, Nicholas D. "Unmasking Horror -- A special report; Japan Confronting Gruesome War Atrocity." The New York Times. March 17, 1995. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.nytimes.com/1995/03/17/world/unmasking-horror-a-special-report-japan-confronting-gruesome-war-atrocity.html

- Landau, Elizabeth. "Studies show 'dark chapter' of medical research." CNN. Oct. 1, 2010. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.cnn.com/2010/HEALTH/10/01/guatemala.syphilis.tuskegee/

- Mayo Clinic. "Stuttering: Causes." Sept. 8, 2011. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/stuttering/basics/causes/con-20032854

- Mayo Clinic. "Syphilis." Jan. 2, 2014. (Aug. 20, 2014) http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/syphilis/basics/definition/con-20021862

- McCurry, Justin. "Japan unearths site linked to human experiments." The Guardian. Feb. 21, 2011. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/feb/21/japan-excavates-site-human-experiments

- McGreal, Chris. "Gays tell of mutilation by apartheid army." The Guardian. July 28, 2000. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.theguardian.com/world/2000/jul/29/chrismcgreal

- Milgram, Stanley. "Behavioral Study of Obedience." Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. No. 67. Pages 371-378. 1963. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://wadsworth.cengage.com/psychology_d/templates/student_resources/0155060678_rathus/ps/ps01.html

- NPR. "Taking A Closer Look At Milgram's Shocking Obedience Study." Aug. 28, 2013. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.npr.org/2013/08/28/209559002/taking-a-closer-look-at-milgrams-shocking-obedience-study

- Rawlings, Nate. "Top 10 Weird Government Secrets: CIA Mind-Control Experiments." Time. Aug. 6, 2010. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2008962_2008964_2008992,00.html

- Reynolds, Gretchen. "The Stuttering Doctor's 'Monster Study'." The New York Times. March 16, 2003. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/16/magazine/the-stuttering-doctor-s-monster-study.html

- Ryall, Julian. "Human bones could reveal truth of Japan's 'Unit 731' experiments." The Telegraph. Feb. 15, 2010. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/japan/7236099/Human-bones-could-reveal-truth-of-Japans-Unit-731-experiments.html

- Science Channel - Dark Matters. "Project MKULTRA." (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.sciencechannel.com/tv-shows/dark-matters-twisted-but-true/documents/project-mkultra.htm

- Shea, Christopher. "Stanley Milgram and the uncertainty of evil." The Boston Globe. Sept. 29, 2013. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2013/09/28/stanley-milgram-and-uncertainty-evil/qUjame9xApiKc6evtgQRqN/story.html

- Shermer, Michael. "What Milgram's Shock Experiments Really Mean." Scientific American. Oct. 16, 2012. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-milgrams-shock-experiments-really-mean/

- Si-Yang Bay, Noel. "Green anatomist herohilus: the father of anatomy." Anatomy & Cell Biology. Vol. 43, No. 4. Pages 280-283. December 2010. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3026179/

- Stobbe, Mike. "Ugly past of U.S. human experiments uncovered." NBC News. Feb. 27, 2011. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.nbcnews.com/id/41811750/ns/health-health_care/t/ugly-past-us-human-experiments-uncovered

- Tuskegee University. "About the USPHS Syphilis Study." (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.tuskegee.edu/about_us/centers_of_excellence/bioethics_center/about_the_usphs_syphilis_study.aspx

- Tyson, Peter. "Holocaust on Trial: The Experiments." PBS. October 2000. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/holocaust/experiside.html

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. "Nazi Medical Experiments." June 20, 2014. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005168

- Van Zul, Mikki. "The Aversion Project." South African medical Research Council. October 1999. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.mrc.ac.za/healthsystems/aversion.pdf

- Watson, John B.; and Rosalie Rayner. "Conditioned Emotional Reactions." Journal of Experimental Psychology. Vol. 3, No. 1. Pages 1-14. 1920. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Watson/emotion.htm

- Wiltse, LL. "Herophilus of Alexandria (325-255 B.C.). The father of anatomy." Spine. Vol. 23, no. 7. Pages 1904-1914. Sept. 1, 1998. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9762750

- Working, Russell. "The trial of Unit 731." June 2001. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2001/06/05/commentary/world-commentary/the-trial-of-unit-731/

- Zetter, Kim. "April 13, 1953: CIA OKs MK-ULTRA Mind-Control Tests." Wired. April 13, 2010. (Aug. 10, 2014) http://www.wired.com/2010/04/0413mk-ultra-authorized/

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

Scientific Experiments That Went Terribly Wrong

Science encompasses a vast range of study fields. With scientific investigation comes responsibility. When ethics or caution are thrown to the wind, or the experiment simply doesn’t work out, disaster and failure can be dramatic. In this account, we discover 10 experiments with some pretty unsatisfactory social outcomes.

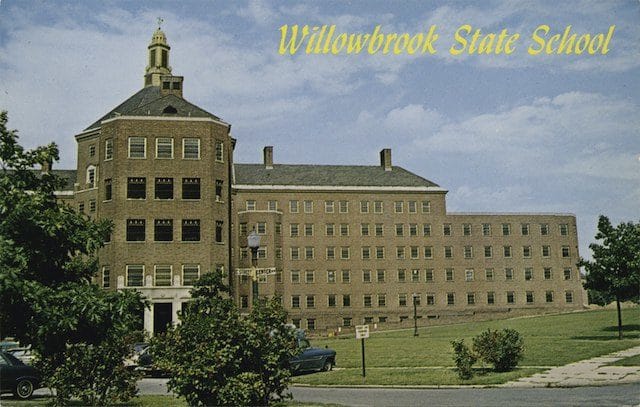

10. Willowbrook State School Hepatitis Tests

At Willowbrook State School , run by the state of New York as a place for children with mental handicaps, outbreaks of hepatitis occurred naturally and also as a result of unethical experimentation. At this Staten Island school, Dr. Saul Krugman conducted some very disturbing experiments where he intentionally infected children with mental disabilities with hepatitis and then monitored the progress of the infection for scientific research purposes.

The research began in 1956 and went on for 14 years. Worse yet, parents were often informed that their children could be admitted provided they consented to hepatitis experiments being done on the children as an alternative to paying high entrance fees. The researchers justified the work by saying that injections intended to fight off hepatitis would be given following purposeful infection, and then claimed that existing infections meant that inducing hepatitis infection should not be viewed too harshly. Some twisted reasoning indeed! A variety of scholarly writers weighed in and offered opinions that included reasons the work should be condemned or defended in a piece titled “The Willowbrook Letters: Criticisms and Defense.”

9. The Ebola Guinea Pig

Ebola might be one of the scariest viruses on Earth, but it has been studied in experiments where one might conclude sufficient caution was lacking. A Russian researcher died when Ebola experimentation led not to study results but death from exposure. While investigating the biology of Ebola virus at the Vector laboratory at Novosibirsk in Siberia, a female researcher poked herself with an Ebola laden needle. The accident at this ultra-secure biological facility involved an Ebola source that might seem surprising: an infected guinea pig being used in the virology study rather than a direct human source.

There are various sub-types of Ebola, but all are dangerous to varying degrees. Infectious and deadly, Ebola will kill between 50 and 90 percent of those infected. Worse, a cure is not yet available for the virus once it is acquired, just management of symptoms. In this accident, the researcher was dead within 14 days of exposure. Unfortunately, Vector officials failed to report the accident right away to the World Health Organization, which is thought to have further reduced the victim’s chances of living.

8. The Madness of Dr. Leo Stanley

Dr. Leo Stanley was one mad scientist whose experiments were founded on dubious or lacking science, and more problematic ethical grounds. Of course, his bizarre experiments ended in harm and often chaos. As the Chief Surgeon of California’s San Quentin Prison , the doctor experimented on the testicles of prisoners with a variety of strange theories to back up his experiments. The things he did are among the most gruesome and bizarre experiments in American history. Take harvesting the testicles from prisoners after their execution and then placing them into the bodies of living prisoners to study male “rejuvenation” while also attempting to gain insight on the “biology of crime” and explore potential means of biological crime control.

It was not enough for this scientist to trade testicles between the living and the dead. He also went full interspecial and began implants of goat, ram and boar testicles into prisoners. Eugenics experiments and forced sterilizations were also among his work. Hundreds of prisoners were subjected to Dr. Stanley’s bizarre research and the harmful results of such non-standard invasions of the human body.

7. The Washington & Oregon Prison Radiation Scandal

When it comes to experiments that end badly, the strange theme of prisoners and terrible, inhumane testicle tests keeps coming up. Is a dishonest and dangerous offer of getting radiated the way to pay for offenses and get out of jail early? From 1963 to 1973, prisoners numbering in the dozens held in Washington and Oregon prison were subjected to doses of radiation to test its effects on — you guessed it — human testes.

With enticement from cash “bribes” and parole hints, 130 inmates let the University of Washington test radiation on them at the behest of the U.S. government. Doses were at 400 rads of radiation, equal to a shocking 2,400 chest x-rays, given in intervals of 10 minutes. The prisoners were not told just how harmful the experimentation was, and received financial settlements through a class-action lawsuit. Dr. Carl Heller, the “ mad scientist ” behind these brutal human radiation experiments, had received $1.2 million in grant money over 10 years contributing to his cruel work. The inmates tested were given vasectomies, in case the radiation damaged their DNA enough to cause them to father children with genetic abnormalities.

6. The Russian Missile Deaths