- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

The american anti-imperialist league at faneuil hall.

Project Gutenberg

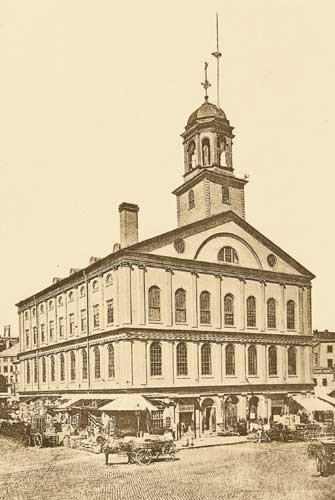

Faneuil Hall has played a central role as a forum and meeting place for political movements throughout Boston's history. These movements covered a broad range of issues, such as labor, women’s suffrage and slavery. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Anti-Imperialist League used Faneuil Hall to protest America’s growing imperialism. The league argued against militarization and the creation of an overseas American Empire and asserted that the principles the United States had been founded upon needed to extend to foreign policy as well.

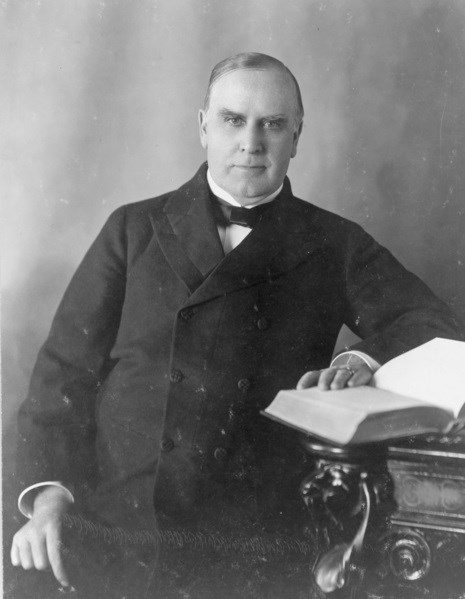

At the turn of the 20 th century, the United States faced a decision. After years of fighting between Spain and Cuba, the Cuban War for Independence had finally reached the widespread attention of the American people. Concerned for the safety of American interests, the government moved the battleship U.S.S. Maine into Havana harbor. Here, the battleship exploded. Many Americans believed Spain had caused the ship’s destruction and the deaths of the sailors onboard. This tragedy resulted in a surge of public support for Cuba, leading Congress to declare war on Spain. In his 1898 State of the Union address, President William McKinley listed the causes for war:

First, in the cause of humanity and to put an end to the barbarities, bloodshed, starvation, and horrible miseries now existing there... Second, we owe it to our citizens in Cuba to afford them that protection and indemnity for life and property which no government there can or will afford, and to that end to terminate the conditions that deprive them of legal protection. Third, the right to intervene may be justified by the very serious injury to the commerce, trade, and business of our people, and by the wanton destruction of property and devastation of the island. Fourth, and which is of the utmost importance, the present condition of affairs in Cuba is a constant menace to our peace, and entails upon this government an enormous expense. [1]

Library of Congress

Although McKinley made lofty claims about fighting on the behalf of democracy, the opening battles of the war alluded to a different agenda. The first American victory of the war occurred in Manila Bay, in the Philippines. Like Cuba, the Philippines had been waging a war for independence against Spain. When American troops arrived in the archipelago, they brought the Philippine’s exiled leader, Emilio Aguinaldo, with them. Aguinaldo rallied the revolutionaries and assisted the American forces in laying siege to Manila.

Some Americans quickly became concerned about the true purpose of the Spanish-American War. While most maintained that the United States aimed to secure Cuban independence, others believed this intervention to be the first step in the formation of an overseas American empire. Imperialism had experienced a global revival in the late 1800s, with the colonization of Africa and the creation of spheres of influence in China. The idea of President McKinley using the Spanish-American War as an excuse to acquire territory outside of North America worried many Americans, inspiring some to act.

On June 2, 1898, Gamaliel Bradford, a retired banker and the son of an abolitionist, published a letter in the Boston Evening Transcript , arranging a meeting to protest the United States’ imperialist policies. This meeting took place in Faneuil Hall on June 15, 1898. [2] At this meeting, Bradford spelled out his concerns:

We are here to insist that a war begun in the cause of humanity shall not be turned into war for empire, that an attempt to win for Cubans the right to govern themselves shall not be made an excuse for extending our sway over alien peoples without their consent. The fundamental principles of our government are at stake. [3]

Boston newspapers covered the meeting extensively, though the rest of the nation seemingly took little notice. On the same day of the Faneuil Hall meeting, Congress voted to annex the island nation of Hawaii. [4] For the first time, the United States' borders had left the American continent. A sovereign nation had been subverted and subsumed by American interests. If the United States took that step with Hawaii, critics thought, what would prevent it from doing the same with Cuba or the Philippines?

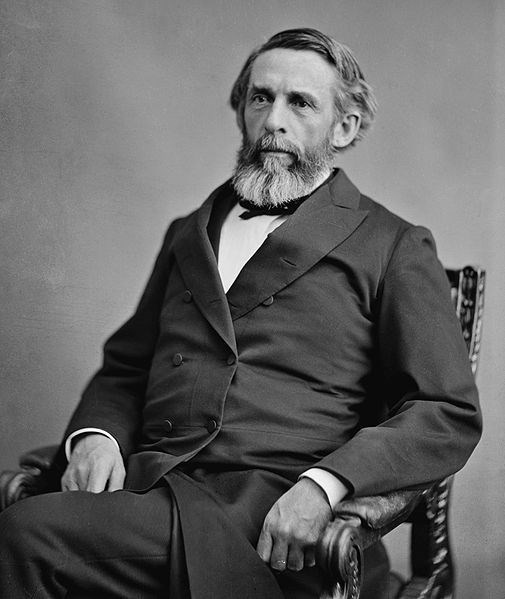

The Anti-Imperialist League officially formed in Boston on November 19, 1898, with the election of George S. Boutwell as the Anti-Imperialist League's first president. [5] A founding member of the Republican Party, Boutwell had previously served as the Governor of Massachusetts. He had led the impeachment of Andrew Johnson during Reconstruction and had served as the Secretary of the Treasury under President Grant. Boutwell left the Republican Party in protest of McKinley's imperialist policies in 1898. [6]

Other important figures of the time joined the Anti-Imperials, including the industrialist Andrew Carnegie and the author Mark Twain. Branches of the league spread across the United States, with Leagues forming in Chicago, Philadelphia, and Washington DC. Despite the growing anti-imperial movement, however, President McKinley and Congress purchased the Philippines from Spain during the 1898 Treaty of Paris, ending the Spanish-American War.

"War In The Philippines,"1899.

Signed on December 10, 1898 and ratified by the United States Congress on February 6, 1899, the Treaty of Paris completely ignored the people of the Philippines, who established the Philippine Republic on January 22, 1899. Emilio Aguinaldo, who had declared Philippine independence and led the war effort before the United States arrived, became the republic’s first President. In an act of blatant hypocrisy, the United States refused to recognize the fledgling government. U.S. troops did not withdraw from Manila. Fighting began almost as soon as the Spanish-American War ended.

The American-Philippine War galvanized the Anti-Imperialists. In a speech at the first annual meeting of the Anti-Imperialist League in Boston, Boutwell argued:

…the President of the United States has entered upon a policy of invasion, of conquest—a policy of vast navies and mighty armies—a policy which will furnish an excuse, and to many a justifying reason for the creation and maintenance of vast navies and mighty armies, through the lifetime of the nation, whether called a republic or empire. Despotism—absolutism in government—is the necessity of the army and the navy, and in such schools and from such training can we expect to create or even to preserve ideas and practices that are consistent with republican institutions? [7]

The League held regular meetings across Boston, including multiple meetings at Faneuil Hall. As with many causes of the day, Faneuil Hall served as a symbol for those meeting within it. The Anti-Imperialists capitalized on the hall’s connection to the American Revolution, arguing that the occupation of the Philippines directly contradicted the Declaration of Independence. George Guylas Miller, the President of the Philadelphia Anti-Imperialist League questioned:

This eighteenth century political philosophy that Jefferson embodied in the Declaration of Independence – is it true? …Is it still an ideal for twentieth-century America, freer and more prosperous than in the days of her youth? Or has plutocracy bred tyrants, and we must give up our ancient faith? [8]

As the League protested American imperialism, the American-Philippine War continued, with US troops capturing Aguinaldo in 1901 with the help of native scouts. Almost immediately after the news of this operation reached Boston, the League held another meeting at Faneuil Hall, where George Miller warned of the growing power of imperialism:

The chairman of this meeting has alluded to the apathy of the American people on this great question. To my mind this is our greatest danger…Imperialism is making progress among us, just as it did in ancient Rome, by gradual stages, and without any clear conception on the part of the people of the trend of affairs. [9]

The capture of Aguinaldo crippled the Philippine resistance. The war officially ended the next year, with the Philippines firmly under United States rule. The League ultimately failed in its goal to prevent the United States from acting as an empire. While the League continued to exist until 1920, the height of its popularity had passed with the end of the American-Philippine War. Anti-imperialist protests against these policies remain unanswered. However, the League left behind a valuable lesson: without public support, even the most idealistic of movements will fail.

Contributed by: Aaron Zack, Park Ranger

[1] "WILLIAM McKINLEY:War Message, 1898," accessed October 1, 2020. https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/mkinly2.htm .

[2] Stephen Kinzer, "'White Peaceful Wings': Debating U.S. Imperialism in 1898." Historic Journal of Massachusetts 48, no. 1 (Winter 2020): 25–45, http://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/True-Flag-FINAL1.pdf , 26.

[3] Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. "Image 4 of Save the Republic. Anti-Imperialist Leaflet No. 11 [-21] [Washington, 1898-99]," Online text, accessed September 16, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.2390200h/?sp=4 .

[4] Kinzer, "'White Peaceful Wings,'" 26.

[5] E. Berkeley Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States: The Great Debate, 1890-1920 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1970), https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv4rft41 , 126.

[6] "George S. Boutwell (1869–1873) | Miller Center," accessed October 4, 2016, https://millercenter.org/president/grant/essays/boutwell-1869-secretary-of-the-treasury .

[7] "1st Meeting, President’s Address, George S. Boutwell," accessed October 11, 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20071011041954/http://www.antiimperialist.com/webroot/AILdocuments/1stMeeting(PrezAdd).html .

[8] Free America, Free Cuba, Free Philippines: Addresses at a Meeting in Faneuil Hall, Saturday, March 30, 1901 (Boston : New England Anti-Imperialist League, 1901), http://archive.org/details/freeamericafreec00unse , 32.

[9] Free America, Free Cuba, Free Philippines , 35.

You Might Also Like

- boston national historical park

- faneuil hall

- anti-imperialism

- president mckinley

- william mckinley

- u.s.s. maine

- spanish american war

- phillipine history

- unfinished 250

Boston National Historical Park

Last updated: January 9, 2024

George Washington Williams and the Origins of Anti-Imperialism

Initially supportive of Belgian King Leopold II’s claim to have created a “free state” of Congo, Williams changed his mind when he saw the horrors of empire.

Historian George Washington Williams died in the English coastal town of Blackpool in 1891, frustrated at a moral, political, and social catastrophe he had witnessed, one that would alter the Black radical tradition for good. Williams discovered, in his trips in the Belgian Congo, a problem that had not yet been named: imperialism. It was barbarism and cruelty thought to have been extinguished with the abolition of slavery. The “free state” of Congo was put to work for King Leopold II of Belgium. Children and old men had their hands cut off for the slightest infractions, an indigenous force founded by the king (the notorious Force Publique ) could, without reservation, destroy whole villages if they refused to work. All subjects of the Free State of Congo were forced to extract rubber from rubber figs. Only free in name, every Congolese citizen was effectively still a slave. Everybody was forced, with a labor tax by Leopold.

When George Washington Williams saw this suffering up close, it was as if he was looking into a mirror, a mirror that showed a bygone age he risked his life to abolish. It looked like chattel slavery.

Empire was as old as hierarchical society itself. Settler colonialism was seen as a solution to the “social problem” of unruly unemployed workers at home in Europe. Steamships took settlers to European-carved “protectorates” to start life anew. In struggles for land and labor, racial segregation, backed by the powerful imperialist state, would soon follow. The barbarisms that were being reported, from the Nama and Herero genocides in present-day Namibia by the Germans to the concentration camps in South Africa by the English to the war crimes by the US in the Philippines, spurred a global movement which called itself “anti-imperialism.”

Williams, however, died before this movement began to take shape. He died before people identified as anti-imperialists, before the American novelist Mark Twain and his contemporaries founded the American Anti-Imperialist League in 1898. He died before the English social scientist J. A. Hobson wrote his influential study, Imperialism: A Study (1902), after witnessing horrors in the Second Boer War in South Africa in 1903.

Williams was a deeply Christian man. He was trained in theology and believed that God directly ruled the affairs of humanity. In his worldview, God tested the patience of humanity but ultimately pushed world affairs toward the arc of justice. The American civil war, which he ran away from home to join at the young age of fourteen, seemed to prove to Williams that behind the Union army—and the end of American slavery—there worked a divine hand. And there was good reason for his optimism: his own life story.

We would have never learned about Williams were it not for a graduate student in 1946, John Hope Franklin, uncovering his comprehensive history of Black America, one of the first of its kind.

During his childhood (in the US), most who shared Williams’ complexion had been condemned to a life of slavery. By his adulthood, during reconstruction, he had stints as a storekeeper for the internal revenue department, as secretary of the four-million-dollar fund to build the Cincinnati Southern Railroad, and served in the State Legislature of Ohio. At one time, Williams was considered for the position of ambassador of the United States to Haiti, a decision made by a Republican administration, but rescinded by Democrats. Williams’ patriotism never wavered, and his optimism was directed toward the improvement of the lot of Black peoples worldwide.

But just as he had come of age in a hopeful moment in American history, i.e., the Emancipation Proclamation, another process had been in motion beyond its shores. From 1800 to 1878, six and a half million square miles of Earth were added to the possessions of Europe. In 1800, that meant Europe owned 55% of the world’s landmass. By 1878, its shared increased to 67%. On the eve of World War I, that became 84% of the globe. Africa was a late target in this partitioning of the world, but by the second half of the nineteenth century, it too was becoming swallowed up by Europe.

In 1884, Bismark claimed southwest Africa, Togoland and the Cameroons, New Guinea and East Africa, Tanganyika within a year. The British had already claimed Egypt and were vying for control with the French in the north of the continent. Tunisia and Algeria were already under French control. Portugal, the oldest colonizer in Africa, had retained her centuries-old claims, and with the collapse of the Dutch East India Company, the British took over present-day South Africa, and shortly after introduced British settlers to the already established polis of the Dutch. This was a messy and dangerous process.

There is a persistent myth that, in 1885, the West African Conference of Berlin divided Africa among Europeans. But by then, the “scramble for Africa” was already well in motion. What the conference did is draw armistice lines for the empires that were now clearly in control of the continent. It was a way to ensure peace so that Europeans could establish “protectorates” over the land they already colonized, according to the late imperial historian George Shepperson.

In Berlin, the scramble for Africa was only recognized, formalized, legitimized, and intensified. Fifteen powers—Germany, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, the United States, France, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Sweden, Norway, and the Ottoman Empire—had gathered in Berlin for two purposes: to recognize European claims to Africa and officially demarcate them on the map, and more importantly, to follow the US in recognizing King Leopold II’s personal claim to the Congo.

Leopold II insisted that designating a colony of his own and calling it the Congo Free State would help abolish slavery in Africa, spread Christianity to its natives, and open up the continent to free trade. Only few, like the first Black Protestant Episcopal Bishop, Theodore Holly, realized that what happened in the Berlin Conference instead was empires who “had come together to enact into law, national rapine, robbery and murder.”

Williams, typical of his time, thought that Leopold was a sincere king. As the historian Robin D. G Kelly puts it : “Scholars as diverse as George Washington Williams, Benjamin Brawley, and Rayford Logan understood imperialism a bearer of modernity for the colored world.” The American poet Hunt Hawkins, based out of Florida State University, demonstrates that Williams appeared before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1884 to urge US recognition of King Leopold’s claim to the Congo. In addition, “he attended an Anti-Slavery Conference in Brussels and proposed to Leopold a scheme for bringing black Americans to work in the Congo.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Leopold was alarmed at the idea that Williams wanted to see the Congo for himself, even urging him to wait. But Williams went anyways. What he witnessed, according to the American journalist and historian Adam Hochschild, was so brutal that, in a confidential letter, Williams accused King Leopold of crimes against humanity, decades before the term would reappear in the Nuremberg trials and become recognized by international law. In an open letter to the King that shook the world, he accused Leopold of having a government which “had sequestered their land, burned their towns, stolen their property, enslaved their women and children, and committed other crimes too numerous to mention in detail.”

A month later, the Polish-British novelist Joseph Conrad followed the same trail that Williams took. His notebook, which made note of the numerous crimes he witnessed, provided the material for his timeless novel Heart of Darkness . Both of them had come back from the Congo, witnessing “the horror!, the horror!” of Leopold’s rule, and avowed a complete renunciation of Empire.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- Gaylord Wilshire’s Boulevard of Marxist Dreams

- How IBM Took Europe

- How Native Americans Guarded Their Societies Against Tyranny

The Invention of the Marathon

Recent posts.

- Azolla filiculoides : Balancing Environmental Promise and Peril

- Sting! (Don’t Stand So Close to the Tarantula Hawk)

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Against American Imperialism

- January 4, 1899

No related resources

Introduction

For many Americans, Carl Schurz (1829–1906) personified the American dream. Schurz immigrated to the United States from Germany in 1852 and eventually settled in Wisconsin, where he practiced law. An avowed opponent of slavery, Schurz became active in the newly created Republican Party and campaigned throughout the Midwest on behalf of presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln in 1860. The newly elected president rewarded Schurz with an appointment as the American ambassador to Spain, where he played a role in keeping that nation from recognizing the Confederacy. He returned home to the United States and in 1862 was appointed a general in the Union army, thanks once again to the intervention of President Lincoln. Schurz settled in Missouri after the war and was elected to the Senate in 1868, becoming the first German-American U.S. senator. In that capacity, Schurz was one of the more outspoken opponents of President Ulysses S. Grant’s proposal to annex Santo Domingo and became a target of Grant’s wrath for his role in defeating the annexation treaty. President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed him secretary of the interior in 1877; following that service Schurz settled permanently in New York, where he became a newspaper editor and a prominent opponent of imperialism. Schurz opposed the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands, claiming that it was “an act of selfish ambition and conquest.” He was outspoken in his opposition to the Spanish-American War, in part fearing the acquisition of territory in the Caribbean and the Pacific would lead to “the moral ruin of the Anglo-Saxon republic.” Schurz correctly predicted that the United States would never give the newly acquired territories the full voice given to American states. “This means government without the consent of the governed. It means taxation without representation. It means the very things against which the Declaration of Independence remonstrated, and against which the Fathers rose in revolution.” This address, delivered at the convocation for the University of Chicago in January 1899, captures the essence of anti-imperialist sentiment on the verge of the twentieth century, “the American century.”

Carl Schurz, “Against American Imperialism,” January 4, 1899, Speeches, Correspondence and Political Papers of Carl Schurz, vol. 6, ed. Frederic Bancroft (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1913), 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 14–15, 26, 27, 29, 30–31, 35–36, available at https://www.google.com/books/edition/Speeches_correspondence_and_political_pa/8R37AwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 .

It is proposed to embark this republic in a course of imperialistic policy by permanently annexing to it certain islands taken, or partly taken, from Spain in the late war. The matter is near its decision, but not yet ratified by the Senate; but even if it were, the question whether those islands, although ceded by Spain, shall be permanently incorporated in the territory of the United States would still be open for final determination by Congress. As an open question therefore I shall discuss it.

. . .It behooves the American people to think and act with calm deliberation, for the character and future of the republic and the welfare of its people now living and yet to be born are in unprecedented jeopardy. . . .

. . . According to the solemn proclamation of our government, [the Spanish-American War] had been undertaken solely for the liberation of Cuba, as a war of humanity and not of conquest. 1 But our easy victories had put conquest within our reach, and when our arms occupied foreign territory, a loud demand arose that, pledge or no pledge to the contrary, the conquests should be kept, even the Philippines on the other side of the globe, and that as to Cuba herself, independence would only be a provisional formality. Why not? was the cry. Has not the career of the republic almost from its very beginning been one of territorial expansion? . . .

Compare now with our old acquisitions as to all these important points those at present in view. They are not continental, not contiguous to our present domain, but beyond seas, the Philippines many thousand miles distant from our coast. They are all situated in the tropics, where people of the northern races, such as Anglo-Saxons, or generally speaking, people of Germanic blood, have never migrated in mass to stay; and they are more or less densely populated, parts of them as densely as Massachusetts—their populations consisting almost exclusively of races to whom the tropical climate is congenial—Spanish creoles mixed with negroes in the West Indies, and Malays, Tagals, Filipinos, Chinese, Japanese, Negritos, and various more or less barbarous tribes in the Philippines. . . .

. . . Whatever we may do for their improvement the people of the Spanish Antilles will remain in overwhelming numerical predominance . . .some of them quite clever in their way, but the vast majority utterly alien to us not only in origin and language, but in habits, traditional ways of thinking, principles, ambitions—in short, in most things that are of the greatest importance in human intercourse and especially in political cooperation. And under the influences of their tropical climate they will prove incapable of becoming assimilated to the Anglo-Saxon. They would, therefore, remain in the population of this republic a hopelessly heterogeneous element—in some respects more hopeless even than the colored people now living among us. . . .

If we [adopt a colonial system], we shall transform the government of the people, for the people, and by the people, for which Abraham Lincoln lived, into a government of one part of the people, the strong, over another part, the weak. Such an abandonment of a fundamental principle as a permanent policy may at first seem to bear only upon more or less distant dependencies, but it can hardly fail in its ultimate effects to disturb the rule of the same principle in the conduct of democratic government at home. And I warn the American people that a democracy cannot so deny its faith as to the vital conditions of its being—it cannot long play the king over subject populations without creating within itself ways of thinking and habits of action most dangerous to its own vitality. . . .

. . .Conservative citizens will tell [the American people] that thus the homogeneousness 2 of the people of the republic, so essential to the working of our democratic institutions, will be irretrievably lost; that our race troubles, already dangerous, will be infinitely aggravated, and that the government of, by, and for the people will be in imminent danger of fatal demoralization. . . .The American people will be driven on and on by the force of events as Napoleon was when he started on his career of limitless conquest. This is imperialism as now advocated. Do we wish to prevent its excesses? Then we must stop at the beginning, before taking Puerto Rico. If we take that island, not even to speak of the Philippines, we shall have placed ourselves on the inclined plane, and roll on and on, no longer masters of our own will, until we have reached the bottom. And where will that bottom be? Who knows? . . .

What can there be to justify a change of policy fraught with such direful consequences? Let us pass the arguments of the advocates of such imperialism candidly in review.

The cry suddenly raised that this great country has become too small for us is too ridiculous to demand an answer, in view of the fact that our present population may be tripled and still have ample elbow room, with resources to support many more. But we are told that our industries are gasping for breath; that we are suffering from overproduction; that our products must have new outlets, and that we need colonies and dependencies the world over to give us more markets. More markets? Certainly. But do we, civilized beings, indulge in the absurd and barbarous notion that we must own the countries with which we wish to trade? . . .

“But the Pacific Ocean,” we are mysteriously told, “will be the great commercial battlefield of the future, and we must quickly use the present opportunity to secure our position on it. The visible presence of great power is necessary for us to get our share of the trade of China. Therefore, we must have the Philippines.” Well, the China trade is worth having, although for a time out of sight the Atlantic Ocean will be an infinitely more important battlefield of commerce.

. . . But does the trade of China really require that we should have the Philippines and make a great display of power to get our share? . . .

“But we must have coaling stations for our navy!” Well, can we not get as many coaling stations as we need without owning populous countries behind them that would entangle us in dangerous political responsibilities and complications? Must Great Britain own the whole of Spain in order to hold Gibraltar? 3

“But we must civilize those poor people!” Are we not ingenious and charitable enough to do much for their civilization without subjugating and ruling them by criminal aggression?

The rest of the pleas for imperialism consist mostly of those high-sounding catchwords of which a free people when about to decide a great question should be especially suspicious. We are admonished that it is time for us to become a “world power.” Well, we are a world power now, and have been for many years. What is a world power? A power strong enough to make its voice listened to with deference by the world whenever it chooses to speak. Is it necessary for a world power, in order to be such, to have its finger in every pie? Must we have the Philippines in order to become a world power? To ask the question is to answer it.

The American flag, we are told, whenever once raised, must never be hauled down. Certainly, every patriotic citizen will always be ready, if need be, to fight and to die under his flag wherever it may wave in justice and for the best interests of the country. But I say to you, woe to the republic if it should ever be without citizens patriotic and brave enough to defy the demagogues’ cry and to haul down the flag wherever it may be raised not in justice and not for the best interests of the country. Such a republic would not last long. . . .

We are told that, having grown so great and strong, we must at last cast off our childish reverence for the teachings of Washington’s Farewell Address 4 — those “nursery rhymes that were sung around the cradle of the Republic.” I apprehend that many of those who now so flippantly scoff at the heritage the Father of his Country left us in his last words of admonition have never read that venerable document. I challenge those who have, to show me a single sentence of general import in it that would not as a wise rule of national conduct apply to the circumstances of today! What is it that has given to Washington’s Farewell Address an authority that was revered by all until our recent victories made so many of us drunk with wild ambitions? Not only the prestige of Washington’s name, great as that was and should ever remain. No, it was the fact that under a respectful observance of those teachings this republic has grown from the most modest beginnings into a union spanning this vast continent; our people have multiplied from a handful to seventy-five million; we have risen from poverty to a wealth the sum of which the imagination can hardly grasp; this American nation has become one of the greatest and most powerful on earth, and continuing in the same course will surely become the greatest and most powerful of all. Not Washington’s name alone gave his teachings their dignity and weight. It was the practical results of his policy that secured to it, until now, the intelligent approbation of the American people. And unless we have completely lost our senses, we shall never despise and reject as mere “nursery rhymes” the words of wisdom left us by the greatest of Americans, following which the American people have achieved a splendor of development without parallel in the history of mankind. . . .

Thus [if the United States abandons imperialism] we shall be their best friends without being their foreign rulers. We shall have done our duty to them, to ourselves, and to the world. However imperfect their governments

may still remain, they will at least be their own, and they will not with their disorders and corruptions contaminate our institutions, the integrity of which is not only to ourselves, but to liberty-loving mankind, the most important concern of all. We may then await the result with generous patience—with the same patience with which for many years we witnessed the revolutionary disorders of Mexico on our very borders, without any thought of taking her government into our own hands.

Ask yourselves whether a policy like this will not raise the American people to a level of moral greatness never before attained! If this democracy, after all the intoxication of triumph in war, conscientiously remembers its professions and pledges, and soberly reflects on its duties to itself and others, and then deliberately resists the temptation of conquest, it will achieve the grandest triumph of the democratic idea that history knows of. It will give the government of, for, and by the people a prestige it never before possessed. It will render the cause of civilization throughout the world a service without parallel. It will put its detractors to shame, and its voice will be heard in the council of nations with more sincere respect and more deference than ever. The American people, having given proof of their strength and also of their honesty and wisdom, will stand infinitely mightier before the world than any number of subjugated vassals could make them. Are not here our best interests moral and material? Is not this genuine glory? Is not this true patriotism?

I call upon all who so believe never to lose heart in the struggle for this great cause, whatever odds may seem to be against us. Let there be no pusillanimous yielding while the final decision is still in the balance. Let us relax no effort in this, the greatest crisis the republic has ever seen. Let us never cease to invoke the good sense, the honesty, and the patriotic pride of the people. Let us raise high the flag of our country—not as an emblem of reckless adventure and greedy conquest, of betrayed professions and broken pledges, of criminal aggression and arbitrary rule over subject populations—but the old, the true flag, the flag of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln; the flag of the government of, for, and by the people; the flag of national faith held sacred and of national honor unsullied; the flag of human rights and of good example to all nations; the flag of true civilization, peace and good-will to all men. Under it let us stand to the last. . . .

- 1. See Requesting A Declaration of War with Spain.

- 2. Having a similar nature or shared characteristics. Schurz viewed the U.S. population as overwhelmingly Anglo-Saxon, and he considered that a hallmark of the nation’s strength. A lack of shared cultural, religious, and racial backgrounds, Schurz believed, would ultimately destroy the nation.

- 3. A British fortress and naval base located at the southern tip of Spain.

- 4. George Washington's Farewell Address.

Annual Message to Congress (1898)

Annual message to congress (1899), see our list of programs.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Check out our collection of primary source readers

Coming soon! World War I & the 1920s!

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Anti-imperialism.

- Robert David Johnson Robert David Johnson Department of History, Brooklyn College

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.149

- Published online: 05 October 2015

The birth of the United States through a successful colonial revolution created a unique nation-state in which anti-imperialist sentiment existed from the nation’s founding. Three broad points are essential in understanding the relationship between anti-imperialism and U.S. foreign relations. First, the United States obviously has had more than its share of imperialist ventures over the course of its history. Perhaps the better way to address the matter is to remark on—at least in comparison to other major powers—how intense a commitment to anti-imperialism has remained among some quarters of the American public and government. Second, the strength of anti-imperialist sentiment has varied widely and often has depended upon domestic developments, such as the emergence of abolitionism before the Civil War or the changing nature of the Progressive movement following World War I. Third, anti-imperialist policy alternatives have enjoyed considerably more support in Congress than in the executive branch.

- Anti-imperialism

- Wilsonianism

- peace movement

- civil rights

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, American History. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 23 November 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.150.64]

- 185.80.150.64

Character limit 500 /500

COMMENTS

Largely an archival collection of primary documents related to anti-imperialist movements with essays that provide historical context, the site is impressive in its breadth of material. The site brings together hundreds of examples of literature, essays, political cartoons, photographs, and advertisements from the 1890s through the 1930s.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Anti-Imperialist League used Faneuil Hall to protest America's growing imperialism. The league argued against militarization and the creation of an overseas American Empire and asserted that the principles the United States had been founded upon needed to extend to foreign policy as well.

He died before people identified as anti-imperialists, before the American novelist Mark Twain and his contemporaries founded the American Anti-Imperialist League in 1898. He died before the English social scientist J. A. Hobson wrote his influential study, Imperialism: A Study (1902), after witnessing horrors in the Second Boer War in South ...

On June 15, 1898, the Anti-imperialist league formed to fight U.S. annexation of the Philippines, citing a variety of reasons ranging from the economic to the legal to the racial to the moral.It included among its members such notables as Andrew Carnegie, Mark Twain, William James, David Starr Jordan, and Samuel Gompers with George S. Boutwell, former secretary of the Treasury and ...

The rest of the pleas for imperialism consist mostly of those high-sounding catchwords of which a free people when about to decide a great question should be especially suspicious. We are admonished that it is time for us to become a "world power." Well, we are a world power now, and have been for many years. What is a world power?

First, the United States obviously has had more than its share of imperialist ventures over the course of its history. Perhaps the better way to address the matter is to remark on—at least in comparison to other major powers—how intense a commitment to anti-imperialism has remained among some quarters of the American public and government.

Mark Twain's Anti-Imperialism Hunt Hawkins Mark Twain's published anti-imperialist writings from 1897 to 1902 have been the subject of numerous studies, starting with a pioneering ar ... Essays (Hawkins) 33 The first, "The Stupendous Procession," gives a mock description of the funeral of Queen Victoria, who died on 22 January 1901. The marching

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is opposition to imperialism or neocolonialism. ... multimedia collection of photographs, video, oral histories and essays. Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism by V.I. Lenin Full text at marxists.org. How Imperialist 'Aid' Blocks Development in Africa by Thomas Sankara, ...

The objective is to have students recognize the contrasting views of the pro- and anti-imperialist arguments and analyze key elements of primary sources surrounding the debate over US imperialism. Using these key elements students will examine, evaluate, and discuss the meaning and message of each document to determine if it is a pro- or anti ...

THE ANTI-IMPERIALIST MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES, 1898-1900 By FRED H. HARRINGTON On May 1, 1898, the Asia-tic Squadron of the United States ... Political Papers of Carl Schurz (New York, 1913), II, 514. ANTI-IMPERIALISM IN THE UNITED STATES 213 'all just government is derived from the consent of the gov-erned'. " 5