Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Global health

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 13, Issue 8

- Clinical course of a 66-year-old man with an acute ischaemic stroke in the setting of a COVID-19 infection

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7441-6952 Saajan Basi 1 , 2 ,

- Mohammad Hamdan 1 and

- Shuja Punekar 1

- 1 Department of Stroke and Acute Medicine , King's Mill Hospital , Sutton-in-Ashfield , UK

- 2 Department of Acute Medicine , University Hospitals of Derby and Burton , Derby , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Saajan Basi; saajan.basi{at}nhs.net

A 66-year-old man was admitted to hospital with a right frontal cerebral infarct producing left-sided weakness and a deterioration in his speech pattern. The cerebral infarct was confirmed with CT imaging. The only evidence of respiratory symptoms on admission was a 2 L oxygen requirement, maintaining oxygen saturations between 88% and 92%. In a matter of hours this patient developed a greater oxygen requirement, alongside reduced levels of consciousness. A positive COVID-19 throat swab, in addition to bilateral pneumonia on chest X-ray and lymphopaenia in his blood tests, confirmed a diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia. A proactive decision was made involving the patients’ family, ward and intensive care healthcare staff, to not escalate care above a ward-based ceiling of care. The patient died 5 days following admission under the palliative care provided by the medical team.

- respiratory medicine

- infectious diseases

- global health

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2020-235920

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2) is a new strain of coronavirus that is thought to have originated in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. In a matter of months, it has erupted from non-existence to perhaps the greatest challenge to healthcare in modern times, grinding most societies globally to a sudden halt. Consequently, the study and research into SARS-CoV-2 is invaluable. Although coronaviruses are common, SARS-CoV-2 appears to be considerably more contagious. The WHO figures into the 2003 SARS-CoV-1 outbreak, from November 2002 to July 2003, indicate a total of 8439 confirmed cases globally. 1 In comparison, during a period of 4 months from December 2019 to July 2020, the number of global cases of COVID-19 reached 10 357 662, increasing exponentially, illustrating how much more contagious SARS-CoV-2 has been. 2

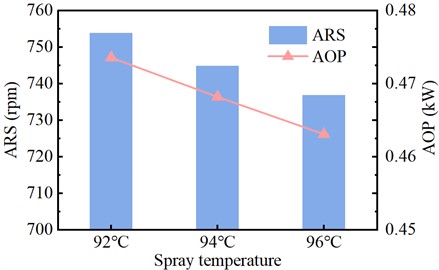

Previous literature has indicated infections, and influenza-like illness have been associated with an overall increase in the odds of stroke development. 3 There appears to be a growing correlation between COVID-19 positive patients presenting to hospital with ischaemic stroke; however, studies investigating this are in progress, with new data emerging daily. This patient report comments on and further characterises the link between COVID-19 pneumonia and the development of ischaemic stroke. At the time of this patients’ admission, there were 95 positive cases from 604 COVID-19 tests conducted in the local community, with a predicted population of 108 000. 4 Only 4 days later, when this patient died, the figure increased to 172 positive cases (81% increase), illustrating the rapid escalation towards the peak of the pandemic, and widespread transmission within the local community ( figure 1 ). As more cases of ischaemic stroke in COVID-19 pneumonia patients arise, the recognition and understanding of its presentation and aetiology can be deciphered. Considering the virulence of SARS-CoV-2 it is crucial as a global healthcare community, we develop this understanding, in order to intervene and reduce significant morbidity and mortality in stroke patients.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

A graph showing the number of patients with COVID-19 in the hospital and in the community over time.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old man presented to the hospital with signs of left-sided weakness. The patient had a background of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), atrial fibrillation and had one previous ischaemic stroke, producing left-sided haemiparesis, which had completely resolved. He was a non-smoker and lived in a house. The patient was found slumped over on the sofa at home on 1 April 2020, by a relative at approximately 01:00, having been seen to have no acute medical illness at 22:00. The patients’ relative initially described disorientation and agitation with weakness noted in the left upper limb and dysarthria. At the time of presentation, neither the patient nor his relative identified any history of fever, cough, shortness of breath, loss of taste, smell or any other symptoms; however, the patient did have a prior admission 9 days earlier with shortness of breath.

The vague nature of symptoms, entwined with considerable concern over approaching the hospital, due to the risk of contracting COVID-19, created a delay in the patients’ attendance to the accident and emergency department. His primary survey conducted at 09:20 on 1 April 2020 demonstrated a patent airway, with spontaneous breathing and good perfusion. His Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 15 (a score of 15 is the highest level of consciousness), his blood glucose was 7.2, and he did not exhibit any signs of trauma. His abbreviated mental test score was 7 out of 10, indicating a degree of altered cognition. An ECG demonstrated atrial fibrillation with a normal heart rate. His admission weight measured 107 kg. At 09:57 the patient required 2 L of nasal cannula oxygen to maintain his oxygen saturations between 88% and 92%. He started to develop agitation associated with an increased respiratory rate at 36 breaths per minute. On auscultation of his chest, he demonstrated widespread coarse crepitation and bilateral wheeze. Throughout he was haemodynamically stable, with a systolic blood pressure between 143 mm Hg and 144 mm Hg and heart rate between 86 beats/min and 95 beats/min. From a neurological standpoint, he had a mild left facial droop, 2/5 power in both lower limbs, 2/5 power in his left upper limb and 5/5 power in his right upper limb. Tone in his left upper limb had increased. This patient was suspected of having COVID-19 pneumonia alongside an ischaemic stroke.

Investigations

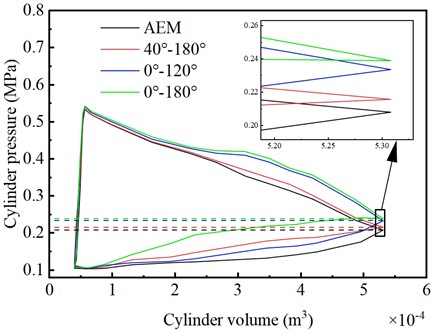

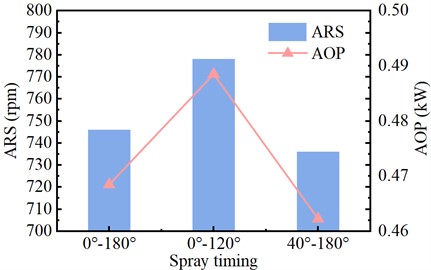

A CT of his brain conducted at 11:38 on 1 April 2020 ( figure 2 ) illustrated an ill-defined hypodensity in the right frontal lobe medially, with sulcal effacement and loss of grey-white matter. This was highly likely to represent acute anterior cerebral artery territory infarction. Furthermore an oval low-density area in the right cerebellar hemisphere, that was also suspicious of an acute infarction. These vascular territories did not entirely correlate with his clinical picture, as limb weakness is not as prominent in anterior cerebral artery territory ischaemia. Therefore this left-sided weakness may have been an amalgamation of residual weakness from his previous stroke, in addition to his acute cerebral infarction. An erect AP chest X-ray with portable equipment ( figure 3 ) conducted on the same day demonstrated patchy peripheral consolidation bilaterally, with no evidence of significant pleural effusion. The pattern of lung involvement raised suspicion of COVID-19 infection, which at this stage was thought to have provoked the acute cerebral infarct. Clinically significant blood results from 1 April 2020 demonstrated a raised C-reactive protein (CRP) at 215 mg/L (normal 0–5 mg/L) and lymphopaenia at 0.5×10 9 (normal 1×10 9 to 3×10 9 ). Other routine blood results are provided in table 1 .

CT imaging of this patients’ brain demonstrating a wedge-shaped infarction of the anterior cerebral artery territory.

Chest X-ray demonstrating the bilateral COVID-19 pneumonia of this patient on admission.

- View inline

Clinical biochemistry and haematology blood results of the patient

Interestingly the patient, in this case, was clinically assessed in the accident and emergency department on 23 March 2020, 9 days prior to admission, with symptoms of shortness of breath. His blood results from this day showed a CRP of 22 mg/L and a greater lymphopaenia at 0.3×10 9 . He had a chest X-ray ( figure 4 ), which indicated mild radiopacification in the left mid zone. He was initially treated with intravenous co-amoxiclav and ciprofloxacin. The following day he had minimal symptoms (CURB 65 score 1 for being over 65 years). Given improving blood results (declining CRP), he was discharged home with a course of oral amoxicillin and clarithromycin. As national governmental restrictions due to COVID-19 had not been formally announced until 23 March 2020, and inconsistencies regarding personal protective equipment training and usage existed during the earlier stages of this rapidly evolving pandemic, it is possible that this patient contracted COVID-19 within the local community, or during his prior hospital admission. It could be argued that the patient had early COVID-19 signs and symptoms, having presented with shortness of breath, lymphopaenia, and having had subtle infective chest X-ray changes. The patient explained he developed a stagnant productive cough, which began 5 days prior to his attendance to hospital on 23 March 2020. He responded to antibiotics, making a full recovery following 7 days of treatment. This information does not assimilate with the typical features of a COVID-19 infection. A diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia or infective exacerbation of COPD seem more likely. However, given the high incidence of COVID-19 infections during this patients’ illness, an exposure and early COVID-19 illness, prior to the 23 March 2020, cannot be completely ruled out.

Chest X-ray conducted on prior admission illustrating mild radiopacification in the left mid zone.

On the current admission, this patient was managed with nasal cannula oxygen at 2 L. By the end of the day, this had progressed to a venturi mask, requiring 8 L of oxygen to maintain oxygen saturation. He had also become increasingly drowsy and confused, his GCS declined from 15 to 12. However, the patient was still haemodynamically stable, as he had been in the morning. An arterial blood gas demonstrated a respiratory alkalosis (pH 7.55, pCO 2 3.1, pO 2 6.7 and HCO 3 24.9, lactate 1.8, base excess 0.5). He was commenced on intravenous co-amoxiclav and ciprofloxacin, to treat a potential exacerbation of COPD. This patient had a COVID-19 throat swab on 1 April 2020. Before the result of this swab, an early discussion was held with the intensive care unit staff, who decided at 17:00 on 1 April 2020 that given the patients presentation, rapid deterioration, comorbidities and likely COVID-19 diagnosis he would not be for escalation to the intensive care unit, and if he were to deteriorate further the end of life pathway would be most appropriate. The discussion was reiterated to the patients’ family, who were in agreement with this. Although he had evidence of an ischaemic stroke on CT of his brain, it was agreed by all clinicians that intervention for this was not as much of a priority as providing optimal palliative care, therefore, a minimally invasive method of treatment was advocated by the stroke team. The patient was given 300 mg of aspirin and was not a candidate for fibrinolysis.

Outcome and follow-up

The following day, before the throat swab result, had appeared the patient deteriorated further, requiring 15 L of oxygen through a non-rebreather face mask at 60% FiO 2 to maintain his oxygen saturation, at a maximum of 88% overnight. At this point, he was unresponsive to voice, with a GCS of 5. Although, he was still haemodynamically stable, with a blood pressure of 126/74 mm Hg and a heart rate of 98 beats/min. His respiratory rate was 30 breaths/min. His worsening respiratory condition, combined with his declining level of consciousness made it impossible to clinically assess progression of the neurological deficit generated by his cerebral infarction. Moreover, the patient was declining sharply while receiving the maximal ward-based treatment available. The senior respiratory physician overseeing the patients’ care decided that a palliative approach was in this his best interest, which was agreed on by all parties. The respiratory team completed the ‘recognising dying’ documentation, which signified that priorities of care had shifted from curative treatment to palliative care. Although the palliative team was not formally involved in the care of the patient, the patient received comfort measures without further attempts at supporting oxygenation, or conduction of regular clinical observations. The COVID-19 throat swab confirmed a positive result on 2 April 2020. The patient was treated by the medical team under jurisdiction of the hospital palliative care team. This included the prescribing of anticipatory medications and a syringe driver, which was established on 3 April 2020. His antibiotic treatment, non-essential medication and intravenous fluid treatment were discontinued. His comatose condition persisted throughout the admission. Once the patients’ GCS was 5, it did not improve. The patient was pronounced dead by doctors at 08:40 on 5 April 2020.

SARS-CoV-2 is a type of coronavirus that was first reported to have caused pneumonia-like infection in humans on 3 December 2019. 5 As a group, coronaviruses are a common cause of upper and lower respiratory tract infections (especially in children) and have been researched extensively since they were first characterised in the 1960s. 6 To date, there are seven coronaviruses that are known to cause infection in humans, including SARS-CoV-1, the first known zoonotic coronavirus outbreak in November 2002. 7 Coronavirus infections pass through communities during the winter months, causing small outbreaks in local communities, that do not cause significant mortality or morbidity.

SARS-CoV-2 strain of coronavirus is classed as a zoonotic coronavirus, meaning the virus pathogen is transmitted from non-humans to cause disease in humans. However the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 indicates human to human transmission is present. From previous research on the transmission of coronaviruses and that of SARS-CoV-2 it can be inferred that SARS-CoV-2 spreads via respiratory droplets, either from direct inhalation, or indirectly touching surfaces with the virus and exposing the eyes, nose or mouth. 8 Common signs and symptoms of the COVID-19 infection identified in patients include high fevers, severe fatigue, dry cough, acute breathing difficulties, bilateral pneumonia on radiological imaging and lymphopaenia. 9 Most of these features were identified in this case study. The significance of COVID-19 is illustrated by the speed of its global spread and the potential to cause severe clinical presentations, which as of April 2020 can only be treated symptomatically. In Italy, as of mid-March 2020, it was reported that 12% of the entire COVID-19 positive population and 16% of all hospitalised patients had an admission to the intensive care unit. 10

The patient, in this case, illustrates the clinical relevance of understanding COVID-19, as he presented with an ischaemic stroke underlined by minimal respiratory symptoms, which progressed expeditiously, resulting in acute respiratory distress syndrome and subsequent death.

Our case is an example of a new and ever-evolving clinical correlation, between patients who present with a radiological confirmed ischaemic stroke and severe COVID-19 pneumonia. As of April 2020, no comprehensive data of the relationship between ischaemic stroke and COVID-19 has been published, however early retrospective case series from three hospitals in Wuhan, China have indicated that up to 36% of COVID-19 patients had neurological manifestations, including stroke. 11 These studies have not yet undergone peer review, but they tell us a great deal about the relationship between COVID-19 and ischaemic stroke, and have been used to influence the American Heart Associations ‘Temporary Emergency Guidance to US Stroke Centres During the COVID-19 Pandemic’. 12

The relationship between similar coronaviruses and other viruses, such as influenza in the development of ischaemic stroke has previously been researched and provide a basis for further investigation, into the prominence of COVID-19 and its relation to ischaemic stroke. 3 Studies of SARS-CoV-2 indicate its receptor-binding region for entry into the host cell is the same as ACE2, which is present on endothelial cells throughout the body. It may be the case that SARS-CoV-2 alters the conventional ability of ACE2 to protect endothelial function in blood vessels, promoting atherosclerotic plaque displacement by producing an inflammatory response, thus increasing the risk of ischaemic stroke development. 13

Other hypothesised reasons for stroke development in COVID-19 patients are the development of hypercoagulability, as a result of critical illness or new onset of arrhythmias, caused by severe infection. Some case studies in Wuhan described immense inflammatory responses to COVID-19, including elevated acute phase reactants, such as CRP and D-dimer. Raised D-dimers are a non-specific marker of a prothrombotic state and have been associated with greater morbidity and mortality relating to stroke and other neurological features. 14

Arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation had been identified in 17% of 138 COVID-19 patients, in a study conducted in Wuhan, China. 15 In this report, the patient was known to have atrial fibrillation and was treated with rivaroxaban. The acute inflammatory state COVID-19 is known to produce had the potential to create a prothrombotic environment, culminating in an ischaemic stroke.

Some early case studies produced in Wuhan describe patients in the sixth decade of life that had not been previously noted to have antiphospholipid antibodies, contain the antibodies in blood results. They are antibodies signify antiphospholipid syndrome; a prothrombotic condition. 16 This raises the hypothesis concerning the ability of COVID-19 to evoke the creation of these antibodies and potentiate thrombotic events, such as ischaemic stroke.

No peer-reviewed studies on the effects of COVID-19 and mechanism of stroke are published as of April 2020; therefore, it is difficult to evidence a specific reason as to why COVID-19 patients are developing neurological signs. It is suspected that a mixture of the factors mentioned above influence the development of ischaemic stroke.

If we delve further into this patients’ comorbid state exclusive to COVID-19 infection, it can be argued that this patient was already at a relatively higher risk of stroke development compared with the general population. The fact this patient had previously had an ischaemic stroke illustrates a prior susceptibility. This patient had a known background of hypertension and atrial fibrillation, which as mentioned previously, can influence blood clot or plaque propagation in the development of an acute ischaemic event. 15 Although the patient was prescribed rivaroxaban as an anticoagulant, true consistent compliance to rivaroxaban or other medications such as amlodipine, clopidogrel, candesartan and atorvastatin cannot be confirmed; all of which can contribute to the reduction of influential factors in the development of ischaemic stroke. Furthermore, the fear of contracting COVID-19, in addition to his vague symptoms, unlike his prior ischaemic stroke, which demonstrated dense left-sided haemiparesis, led to a delay in presentation to hospital. This made treatment options like fibrinolysis unachievable, although it can be argued that if he was already infected with COVID-19, he would have still developed life-threatening COVID-19 pneumonia, regardless of whether he underwent fibrinolysis. It is therefore important to consider that if this patient did not contract COVID-19 pneumonia, he still had many risk factors that made him prone to ischaemic stroke formation. Thus, we must consider whether similar patients would suffer from ischaemic stroke, regardless of COVID-19 infection and whether COVID-19 impacts on the severity of the stroke as an entity.

Having said this, the management of these patients is dependent on the likelihood of a positive outcome from the COVID-19 infection. Establishing the ceiling of care is crucial, as it prevents incredibly unwell or unfit patients’ from going through futile treatments, ensuring respect and dignity in death, if this is the likely outcome. It also allows for the provision of limited or intensive resources, such as intensive care beds or endotracheal intubation during the COVID-19 pandemic, to those who are assessed by the multidisciplinary team to benefit the most from their use. The way to establish this ceiling of care is through an early multidisciplinary discussion. In this case, the patient did not convey his wishes regarding his care to the medical team or his family; therefore it was decided among intensive care specialists, respiratory physicians, stroke physicians and the patients’ relatives. The patient was discussed with the intensive care team, who decided that as the patient sustained two acute life-threatening illnesses simultaneously and had rapidly deteriorated, ward-based care with a view to palliate if the further deterioration was in the patients’ best interests. These decisions were not easy to make, especially as it was on the first day of presentation. This decision was made in the context of the patients’ comorbidities, including COPD, the patients’ age, and the availability of intensive care beds during the steep rise in intensive care admissions, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic ( figure 1 ). Furthermore, the patients’ rapid and permanent decline in GCS, entwined with the severe stroke on CT imaging of the brain made it more unlikely that significant and permanent recovery could be achieved from mechanical intubation, especially as the damage caused by the stroke could not be significantly reversed. As hospitals manage patients with COVID-19 in many parts of the world, there may be tension between the need to provide higher levels of care for an individual patient and the need to preserve finite resources to maximise the benefits for most patients. This patient presented during a steep rise in intensive care admissions, which may have influenced the early decision not to treat the patient in an intensive care setting. Retrospective studies from Wuhan investigating mortality in patients with multiple organ failure, in the setting of COVID-19, requiring intubation have demonstrated mortality can be up to 61.5%. 17 The mortality risk is even higher in those over 65 years of age with respiratory comorbidities, indicating why this patient was unlikely to survive an admission to the intensive care unit. 18

Regularly updating the patients’ family ensured cooperation, empathy and sympathy. The patients’ stroke was not seen as a priority given the severity of his COVID-19 pneumonia, therefore the least invasive, but most appropriate treatment was provided for his stroke. The British Association of Stroke Physicians advocate this approach and also request the notification to their organisation of COVID-19-related stroke cases, in the UK. 19

Learning points

SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2) is one of seven known coronaviruses that commonly cause upper and lower respiratory tract infections. It is the cause of the 2019–2020 global coronavirus pandemic.

The significance of COVID-19 is illustrated by the rapid speed of its spread globally and the potential to cause severe clinical presentations, such as ischaemic stroke.

Early retrospective data has indicated that up to 36% of COVID-19 patients had neurological manifestations, including stroke.

Potential mechanisms behind stroke in COVID-19 patients include a plethora of hypercoagulability secondary to critical illness and systemic inflammation, the development of arrhythmia, alteration to the vascular endothelium resulting in atherosclerotic plaque displacement and dehydration.

It is vital that effective, open communication between the multidisciplinary team, patient and patients relatives is conducted early in order to firmly establish the most appropriate ceiling of care for the patient.

- Cannine M , et al

- Wunderink RG

- van Doremalen N ,

- Bushmaker T ,

- Morris DH , et al

- Wang X-G , et al

- Grasselli G ,

- Pesenti A ,

- Wang M , et al

- American Stroke Assocation, 2020

- Zhang Y-H ,

- Zhang Y-huan ,

- Dong X-F , et al

- Li X , et al

- Hu C , et al

- Zhang S , et al

- Jiang B , et al

- Xu J , et al

- British Association of Stroke Physicians

Contributors SB was involved in the collecting of information for the case, the initial written draft of the case and researching existing data on acute stroke and COVID-19. He also edited drafts of the report. MH was involved in reviewing and editing drafts of the report and contributing new data. SP oversaw the conduction of the project and contributed addition research papers.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Next of kin consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Subscribe or Renew

Create an E-mail Alert for This Article

Case 6-2023: a 68-year-old man with recurrent strokes, permissions, information & authors, metrics & citations, continue reading this article.

Select an option below:

Create your account to get 2 free subscriber-only articles each month.

Already have an account, print subscriber, supplementary material, information, published in, translation.

- Clinical Medicine General

- Emergency Medicine General

- Hospital-Based Clinical Medicine

- Neurology/Neurosurgery General

- Outpatient-Based Clinical Medicine

- Rheumatology General

- Stroke (Emergency Medicine)

- Stroke (Neurology/Neurosurgery)

Affiliations

Export citation.

Select the format you want to export the citation of this publication.

- Igor Gomes Padilha,

- Ahmad Nehme,

- Hubert de Boysson,

- Laurent Létourneau-Guillon,

View Options

View options, content link.

Copying failed.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

Next article, create your account for 2 free subscriber-only articles each month. get free access now..

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Neurotherapy for stroke rehabilitation: A single case study

1995, Biofeedback and Self-Regulation

Related Papers

Basic and Clinical Neuroscience Journal

Introduction: Depression is a mental disorder that highly associated with immune system. Therefore, this study compares the serum concentrations of IL-21, IL-17, and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) between patients with major depressive disorder and healthy controls. Methods: Blood samples were collected from 41 patients with major depressive disorder and 40 healthy age-matched controls with no history of malignancies or autoimmune disorders. The subjects were interviewed face to face according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. Depression score was measured using completed Beck Depression Inventory in both groups. The serum concentrations of IL-21, IL-17, and TGF-β were assessed using ELISA. Results: The mean score of Beck Depression score in the patient and control groups was 35.4±5.5 and 11.1±2.3. IL-17 serum concentrations in the patients and the control group were 10.03±0.6 and 7.6±0.6 pg/mL, respectively (P=0.0002). TGF-β level in the patients group was significantly higher than compare to the control group; 336.7±20.19 vs. 174.8±27.20 pg/mL, (P<0.0001). However, the level of IL-21 was not statistically different between the two groups 84.30±4.57 vs. 84.12±4.15 pg/mL (P>0.05). Conclusion: Considering pro-inflammatory cytokines, current results support the association of inflammatory response and depressive disorder. So, it seems that pro-inflammatory factors profile can be used as indicator in following of depression progress and its treatment impacts.

Neurofeedback and Neuromodulation Techniques and Applications

Gabriel Tan

Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback

kirtley thornton

The onset of cognitive rehabilitation brought with it a hope for an effective treatment for the traumatic brain injured subject. This paper reviews the empirical reports of changes in cognitive functioning after treatment and compares the relative effectiveness of several treatments including computer interventions, cognitive strategies, EEG biofeedback, and medications. The cognitive functions that are reviewed include auditory memory, attention and problem solving. The significance of the change in cognitive function is assessed in two ways that include effect size and longevity of effect. These analyses complement the previously published meta-reviews by adding these two criteria and include reports of EEG biofeedback, which is shown to be an effective intervention for auditory memory.

Journal of Neurotherapy

Leslie Sherlin

John gruzelier

Introduction to Quantitative EEG and Neurofeedback

Victoria L. Ibric , Liviu Dragomirescu

Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America

NeuroRegulation

Journal of Clinical Psychology

Horst Mueller

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Seminars in Pediatric Neurology

Siegfried Othmer

Mahnaz Moghanloo

Ayben Ertem

Marco Congedo , Jan de Moor

Carlos Novo

Marvin W Sams

Malu Mascarenhas de Matos

Jeff La Marca

David Trudeau

Joshua Baruth , Ayman El-baz

Dennis Carmody

BRAIN. Broad Research in Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience ISSN 2067-3957

Academia EduSoft

Dave Siever

Arnaud Delorme

Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback

Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences

Lewis Opler , Paul Ramirez

Autism Spectrum Disorders - From Genes to Environment

Jan de Moor

BMC Psychiatry

Irene Elgen , N. Duric

fateme dehghani arani

Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD

Marbella Espino

Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America - CHILD ADOLESC PSYCHIATR CLIN

Http Dx Doi Org 10 1300 J184v08n02_03

Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders

Michael Datko

Dave Siever , -Dave Siever

George Lindenfeld , John Hummer , James C Miller

Ann N Y Acad Sci

Paul Ramirez

Efthymios Angelakis , Joel Lubar

Meng Yie V Si Toh

Journal of …

David Trudeau , Joel Lubar , Robert Gurnee , Robert Thatcher

Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment

Saroja Krishnaswamy , Jamaludin Mohamed

Dove Medical Press

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

🎁🎄❄️ 50% Off Sale! ❄️ 🎄🎁

🌞🏝️😎 24 hours left to save 50% off our courses 😎 🏝️🌞, 😎 🏝️🌞 24 hours left to save 50% off our courses 😎 🏝️🌞, ❄️ 50% off holiday sale ❄️, emotional freedom techniques for stroke rehabilitation: a single case study.

Citation (APA style): Fuller, S. A., & Stapleton, P. (2021). Emotional Freedom Techniques for Stroke Rehabilitation: A Single Case Study. OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine, 6 (4), 1-1.

Stroke, emotional freedom technique, tapping, guided imagery, visualization, cerebral, single case, depression, anxiety, trauma

Emotional Freedom Techniques or “EFT Tapping” is a powerful self-help method based on research showing that emotional trauma compromises both physical and emotional health.

Customer Support: +1 (877) 461-4026 Email

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

We value your privacy and never share your information. Includes free subscription to our awesome newsletter and promotional e-list and you agree to our terms of use and privacy policy .

Legal | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Testimonials And Results Disclosure | Affiliate Disclosure | Earnings Disclaimer

Emotional Freedom Techniques for Stroke Rehabilitation: A Single Case Study

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- Bond University

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Ann-Charlotte Laska

- Hayley Maree O’Neill

- Aytul Cakci

- Marit Kirkevold

- Line Kildal Bragstad

- John McLeod

- BBA-MOL BASIS DIS

- Alberto Zaliani

- Paola Baiardi

- Joyce A Kootker

- Frederik C. Lem

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 7: 10 Real Cases on Transient Ischemic Attack and Stroke: Diagnosis, Management, and Follow-Up

Jeirym Miranda; Fareeha S. Alavi; Muhammad Saad

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Case review, case discussion, clinical symptoms.

- Radiologic Findings

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Case 1: Management of Acute Thrombotic Cerebrovascular Accident Post Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator Therapy

A 59-year-old Hispanic man presented with right upper and lower extremity weakness, associated with facial drop and slurred speech starting 2 hours before the presentation. He denied visual disturbance, headache, chest pain, palpitations, dyspnea, dysphagia, fever, dizziness, loss of consciousness, bowel or urinary incontinence, or trauma. His medical history was significant for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and benign prostatic hypertrophy. Social history included cigarette smoking (1 pack per day for 20 years) and alcohol intake of 3 to 4 beers daily. Family history was not significant, and he did not remember his medications. In the emergency department, his vital signs were stable. His physical examination was remarkable for right-sided facial droop, dysarthria, and right-sided hemiplegia. The rest of the examination findings were insignificant. His National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was calculated as 7. Initial CT angiogram of head and neck reported no acute intracranial findings. The neurology team was consulted, and intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) was administered along with high-intensity statin therapy. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit where his hemodynamics were monitored for 24 hours and later transferred to the telemetry unit. MRI of the head revealed an acute 1.7-cm infarct of the left periventricular white matter and posterior left basal ganglia. How would you manage this case?

This case scenario presents a patient with acute ischemic cerebrovascular accident (CVA) requiring intravenous t-PA. Diagnosis was based on clinical neurologic symptoms and an NIHSS score of 7 and was later confirmed by neuroimaging. He had multiple comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and smoking history, which put him at a higher risk for developing cardiovascular disease. Because his symptoms started within 4.5 hours of presentation, he was deemed to be a candidate for thrombolytics. The eligibility time line is estimated either by self-report or last witness of baseline status.

Ischemic strokes are caused by an obstruction of a blood vessel, which irrigates the brain mainly secondary to the development of atherosclerotic changes, leading to cerebral thrombosis and embolism. Diagnosis is made based on presenting symptoms and CT/MRI of the head, and the treatment is focused on cerebral reperfusion based on eligibility criteria and timing of presentation.

Symptoms include alteration of sensorium, numbness, decreased motor strength, facial drop, dysarthria, ataxia, visual disturbance, dizziness, and headache.

Get Free Access Through Your Institution

Pop-up div successfully displayed.

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMJ Case Rep

Case report

Clinical course of a 66-year-old man with an acute ischaemic stroke in the setting of a covid-19 infection, saajan basi.

1 Department of Stroke and Acute Medicine, King's Mill Hospital, Sutton-in-Ashfield, UK

2 Department of Acute Medicine, University Hospitals of Derby and Burton, Derby, UK

Mohammad Hamdan

Shuja punekar.

A 66-year-old man was admitted to hospital with a right frontal cerebral infarct producing left-sided weakness and a deterioration in his speech pattern. The cerebral infarct was confirmed with CT imaging. The only evidence of respiratory symptoms on admission was a 2 L oxygen requirement, maintaining oxygen saturations between 88% and 92%. In a matter of hours this patient developed a greater oxygen requirement, alongside reduced levels of consciousness. A positive COVID-19 throat swab, in addition to bilateral pneumonia on chest X-ray and lymphopaenia in his blood tests, confirmed a diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia. A proactive decision was made involving the patients’ family, ward and intensive care healthcare staff, to not escalate care above a ward-based ceiling of care. The patient died 5 days following admission under the palliative care provided by the medical team.

SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2) is a new strain of coronavirus that is thought to have originated in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. In a matter of months, it has erupted from non-existence to perhaps the greatest challenge to healthcare in modern times, grinding most societies globally to a sudden halt. Consequently, the study and research into SARS-CoV-2 is invaluable. Although coronaviruses are common, SARS-CoV-2 appears to be considerably more contagious. The WHO figures into the 2003 SARS-CoV-1 outbreak, from November 2002 to July 2003, indicate a total of 8439 confirmed cases globally. 1 In comparison, during a period of 4 months from December 2019 to July 2020, the number of global cases of COVID-19 reached 10 357 662, increasing exponentially, illustrating how much more contagious SARS-CoV-2 has been. 2

Previous literature has indicated infections, and influenza-like illness have been associated with an overall increase in the odds of stroke development. 3 There appears to be a growing correlation between COVID-19 positive patients presenting to hospital with ischaemic stroke; however, studies investigating this are in progress, with new data emerging daily. This patient report comments on and further characterises the link between COVID-19 pneumonia and the development of ischaemic stroke. At the time of this patients’ admission, there were 95 positive cases from 604 COVID-19 tests conducted in the local community, with a predicted population of 108 000. 4 Only 4 days later, when this patient died, the figure increased to 172 positive cases (81% increase), illustrating the rapid escalation towards the peak of the pandemic, and widespread transmission within the local community ( figure 1 ). As more cases of ischaemic stroke in COVID-19 pneumonia patients arise, the recognition and understanding of its presentation and aetiology can be deciphered. Considering the virulence of SARS-CoV-2 it is crucial as a global healthcare community, we develop this understanding, in order to intervene and reduce significant morbidity and mortality in stroke patients.

A graph showing the number of patients with COVID-19 in the hospital and in the community over time.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old man presented to the hospital with signs of left-sided weakness. The patient had a background of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), atrial fibrillation and had one previous ischaemic stroke, producing left-sided haemiparesis, which had completely resolved. He was a non-smoker and lived in a house. The patient was found slumped over on the sofa at home on 1 April 2020, by a relative at approximately 01:00, having been seen to have no acute medical illness at 22:00. The patients’ relative initially described disorientation and agitation with weakness noted in the left upper limb and dysarthria. At the time of presentation, neither the patient nor his relative identified any history of fever, cough, shortness of breath, loss of taste, smell or any other symptoms; however, the patient did have a prior admission 9 days earlier with shortness of breath.

The vague nature of symptoms, entwined with considerable concern over approaching the hospital, due to the risk of contracting COVID-19, created a delay in the patients’ attendance to the accident and emergency department. His primary survey conducted at 09:20 on 1 April 2020 demonstrated a patent airway, with spontaneous breathing and good perfusion. His Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 15 (a score of 15 is the highest level of consciousness), his blood glucose was 7.2, and he did not exhibit any signs of trauma. His abbreviated mental test score was 7 out of 10, indicating a degree of altered cognition. An ECG demonstrated atrial fibrillation with a normal heart rate. His admission weight measured 107 kg. At 09:57 the patient required 2 L of nasal cannula oxygen to maintain his oxygen saturations between 88% and 92%. He started to develop agitation associated with an increased respiratory rate at 36 breaths per minute. On auscultation of his chest, he demonstrated widespread coarse crepitation and bilateral wheeze. Throughout he was haemodynamically stable, with a systolic blood pressure between 143 mm Hg and 144 mm Hg and heart rate between 86 beats/min and 95 beats/min. From a neurological standpoint, he had a mild left facial droop, 2/5 power in both lower limbs, 2/5 power in his left upper limb and 5/5 power in his right upper limb. Tone in his left upper limb had increased. This patient was suspected of having COVID-19 pneumonia alongside an ischaemic stroke.

Investigations

A CT of his brain conducted at 11:38 on 1 April 2020 ( figure 2 ) illustrated an ill-defined hypodensity in the right frontal lobe medially, with sulcal effacement and loss of grey-white matter. This was highly likely to represent acute anterior cerebral artery territory infarction. Furthermore an oval low-density area in the right cerebellar hemisphere, that was also suspicious of an acute infarction. These vascular territories did not entirely correlate with his clinical picture, as limb weakness is not as prominent in anterior cerebral artery territory ischaemia. Therefore this left-sided weakness may have been an amalgamation of residual weakness from his previous stroke, in addition to his acute cerebral infarction. An erect AP chest X-ray with portable equipment ( figure 3 ) conducted on the same day demonstrated patchy peripheral consolidation bilaterally, with no evidence of significant pleural effusion. The pattern of lung involvement raised suspicion of COVID-19 infection, which at this stage was thought to have provoked the acute cerebral infarct. Clinically significant blood results from 1 April 2020 demonstrated a raised C-reactive protein (CRP) at 215 mg/L (normal 0–5 mg/L) and lymphopaenia at 0.5×10 9 (normal 1×10 9 to 3×10 9 ). Other routine blood results are provided in table 1 .

CT imaging of this patients’ brain demonstrating a wedge-shaped infarction of the anterior cerebral artery territory.

Chest X-ray demonstrating the bilateral COVID-19 pneumonia of this patient on admission.

Clinical biochemistry and haematology blood results of the patient

| Hb | 157 g/L |

| WCC | 5.8 |

| Platelet count | 195 |

| MCV | 86 |

| Neutrophils | 4.9 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.5 |

| INR | 1.3 |

| PT | 16.7 |

| APTT | 28 |

| Sodium | 137 |

| Potassium | Sample haemolysed |

| Urea | 9.5 |

| Creatinine | 84 |

| eGFR | 83 |

| Bilirubin | 26 |

| Albumin | 29 |

| CRP | 215 |

| Total protein | 69 |

APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; CRP, C-reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Hb, haemoglobin; INR, international normalised ratio; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; PT, prothrombin time; WCC, white cell count.

Interestingly the patient, in this case, was clinically assessed in the accident and emergency department on 23 March 2020, 9 days prior to admission, with symptoms of shortness of breath. His blood results from this day showed a CRP of 22 mg/L and a greater lymphopaenia at 0.3×10 9 . He had a chest X-ray ( figure 4 ), which indicated mild radiopacification in the left mid zone. He was initially treated with intravenous co-amoxiclav and ciprofloxacin. The following day he had minimal symptoms (CURB 65 score 1 for being over 65 years). Given improving blood results (declining CRP), he was discharged home with a course of oral amoxicillin and clarithromycin. As national governmental restrictions due to COVID-19 had not been formally announced until 23 March 2020, and inconsistencies regarding personal protective equipment training and usage existed during the earlier stages of this rapidly evolving pandemic, it is possible that this patient contracted COVID-19 within the local community, or during his prior hospital admission. It could be argued that the patient had early COVID-19 signs and symptoms, having presented with shortness of breath, lymphopaenia, and having had subtle infective chest X-ray changes. The patient explained he developed a stagnant productive cough, which began 5 days prior to his attendance to hospital on 23 March 2020. He responded to antibiotics, making a full recovery following 7 days of treatment. This information does not assimilate with the typical features of a COVID-19 infection. A diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia or infective exacerbation of COPD seem more likely. However, given the high incidence of COVID-19 infections during this patients’ illness, an exposure and early COVID-19 illness, prior to the 23 March 2020, cannot be completely ruled out.

Chest X-ray conducted on prior admission illustrating mild radiopacification in the left mid zone.

On the current admission, this patient was managed with nasal cannula oxygen at 2 L. By the end of the day, this had progressed to a venturi mask, requiring 8 L of oxygen to maintain oxygen saturation. He had also become increasingly drowsy and confused, his GCS declined from 15 to 12. However, the patient was still haemodynamically stable, as he had been in the morning. An arterial blood gas demonstrated a respiratory alkalosis (pH 7.55, pCO 2 3.1, pO 2 6.7 and HCO 3 24.9, lactate 1.8, base excess 0.5). He was commenced on intravenous co-amoxiclav and ciprofloxacin, to treat a potential exacerbation of COPD. This patient had a COVID-19 throat swab on 1 April 2020. Before the result of this swab, an early discussion was held with the intensive care unit staff, who decided at 17:00 on 1 April 2020 that given the patients presentation, rapid deterioration, comorbidities and likely COVID-19 diagnosis he would not be for escalation to the intensive care unit, and if he were to deteriorate further the end of life pathway would be most appropriate. The discussion was reiterated to the patients’ family, who were in agreement with this. Although he had evidence of an ischaemic stroke on CT of his brain, it was agreed by all clinicians that intervention for this was not as much of a priority as providing optimal palliative care, therefore, a minimally invasive method of treatment was advocated by the stroke team. The patient was given 300 mg of aspirin and was not a candidate for fibrinolysis.

Outcome and follow-up

The following day, before the throat swab result, had appeared the patient deteriorated further, requiring 15 L of oxygen through a non-rebreather face mask at 60% FiO 2 to maintain his oxygen saturation, at a maximum of 88% overnight. At this point, he was unresponsive to voice, with a GCS of 5. Although, he was still haemodynamically stable, with a blood pressure of 126/74 mm Hg and a heart rate of 98 beats/min. His respiratory rate was 30 breaths/min. His worsening respiratory condition, combined with his declining level of consciousness made it impossible to clinically assess progression of the neurological deficit generated by his cerebral infarction. Moreover, the patient was declining sharply while receiving the maximal ward-based treatment available. The senior respiratory physician overseeing the patients’ care decided that a palliative approach was in this his best interest, which was agreed on by all parties. The respiratory team completed the ‘recognising dying’ documentation, which signified that priorities of care had shifted from curative treatment to palliative care. Although the palliative team was not formally involved in the care of the patient, the patient received comfort measures without further attempts at supporting oxygenation, or conduction of regular clinical observations. The COVID-19 throat swab confirmed a positive result on 2 April 2020. The patient was treated by the medical team under jurisdiction of the hospital palliative care team. This included the prescribing of anticipatory medications and a syringe driver, which was established on 3 April 2020. His antibiotic treatment, non-essential medication and intravenous fluid treatment were discontinued. His comatose condition persisted throughout the admission. Once the patients’ GCS was 5, it did not improve. The patient was pronounced dead by doctors at 08:40 on 5 April 2020.

SARS-CoV-2 is a type of coronavirus that was first reported to have caused pneumonia-like infection in humans on 3 December 2019. 5 As a group, coronaviruses are a common cause of upper and lower respiratory tract infections (especially in children) and have been researched extensively since they were first characterised in the 1960s. 6 To date, there are seven coronaviruses that are known to cause infection in humans, including SARS-CoV-1, the first known zoonotic coronavirus outbreak in November 2002. 7 Coronavirus infections pass through communities during the winter months, causing small outbreaks in local communities, that do not cause significant mortality or morbidity.

SARS-CoV-2 strain of coronavirus is classed as a zoonotic coronavirus, meaning the virus pathogen is transmitted from non-humans to cause disease in humans. However the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 indicates human to human transmission is present. From previous research on the transmission of coronaviruses and that of SARS-CoV-2 it can be inferred that SARS-CoV-2 spreads via respiratory droplets, either from direct inhalation, or indirectly touching surfaces with the virus and exposing the eyes, nose or mouth. 8 Common signs and symptoms of the COVID-19 infection identified in patients include high fevers, severe fatigue, dry cough, acute breathing difficulties, bilateral pneumonia on radiological imaging and lymphopaenia. 9 Most of these features were identified in this case study. The significance of COVID-19 is illustrated by the speed of its global spread and the potential to cause severe clinical presentations, which as of April 2020 can only be treated symptomatically. In Italy, as of mid-March 2020, it was reported that 12% of the entire COVID-19 positive population and 16% of all hospitalised patients had an admission to the intensive care unit. 10

The patient, in this case, illustrates the clinical relevance of understanding COVID-19, as he presented with an ischaemic stroke underlined by minimal respiratory symptoms, which progressed expeditiously, resulting in acute respiratory distress syndrome and subsequent death.

Our case is an example of a new and ever-evolving clinical correlation, between patients who present with a radiological confirmed ischaemic stroke and severe COVID-19 pneumonia. As of April 2020, no comprehensive data of the relationship between ischaemic stroke and COVID-19 has been published, however early retrospective case series from three hospitals in Wuhan, China have indicated that up to 36% of COVID-19 patients had neurological manifestations, including stroke. 11 These studies have not yet undergone peer review, but they tell us a great deal about the relationship between COVID-19 and ischaemic stroke, and have been used to influence the American Heart Associations ‘Temporary Emergency Guidance to US Stroke Centres During the COVID-19 Pandemic’. 12

The relationship between similar coronaviruses and other viruses, such as influenza in the development of ischaemic stroke has previously been researched and provide a basis for further investigation, into the prominence of COVID-19 and its relation to ischaemic stroke. 3 Studies of SARS-CoV-2 indicate its receptor-binding region for entry into the host cell is the same as ACE2, which is present on endothelial cells throughout the body. It may be the case that SARS-CoV-2 alters the conventional ability of ACE2 to protect endothelial function in blood vessels, promoting atherosclerotic plaque displacement by producing an inflammatory response, thus increasing the risk of ischaemic stroke development. 13

Other hypothesised reasons for stroke development in COVID-19 patients are the development of hypercoagulability, as a result of critical illness or new onset of arrhythmias, caused by severe infection. Some case studies in Wuhan described immense inflammatory responses to COVID-19, including elevated acute phase reactants, such as CRP and D-dimer. Raised D-dimers are a non-specific marker of a prothrombotic state and have been associated with greater morbidity and mortality relating to stroke and other neurological features. 14

Arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation had been identified in 17% of 138 COVID-19 patients, in a study conducted in Wuhan, China. 15 In this report, the patient was known to have atrial fibrillation and was treated with rivaroxaban. The acute inflammatory state COVID-19 is known to produce had the potential to create a prothrombotic environment, culminating in an ischaemic stroke.

Some early case studies produced in Wuhan describe patients in the sixth decade of life that had not been previously noted to have antiphospholipid antibodies, contain the antibodies in blood results. They are antibodies signify antiphospholipid syndrome; a prothrombotic condition. 16 This raises the hypothesis concerning the ability of COVID-19 to evoke the creation of these antibodies and potentiate thrombotic events, such as ischaemic stroke.

No peer-reviewed studies on the effects of COVID-19 and mechanism of stroke are published as of April 2020; therefore, it is difficult to evidence a specific reason as to why COVID-19 patients are developing neurological signs. It is suspected that a mixture of the factors mentioned above influence the development of ischaemic stroke.

If we delve further into this patients’ comorbid state exclusive to COVID-19 infection, it can be argued that this patient was already at a relatively higher risk of stroke development compared with the general population. The fact this patient had previously had an ischaemic stroke illustrates a prior susceptibility. This patient had a known background of hypertension and atrial fibrillation, which as mentioned previously, can influence blood clot or plaque propagation in the development of an acute ischaemic event. 15 Although the patient was prescribed rivaroxaban as an anticoagulant, true consistent compliance to rivaroxaban or other medications such as amlodipine, clopidogrel, candesartan and atorvastatin cannot be confirmed; all of which can contribute to the reduction of influential factors in the development of ischaemic stroke. Furthermore, the fear of contracting COVID-19, in addition to his vague symptoms, unlike his prior ischaemic stroke, which demonstrated dense left-sided haemiparesis, led to a delay in presentation to hospital. This made treatment options like fibrinolysis unachievable, although it can be argued that if he was already infected with COVID-19, he would have still developed life-threatening COVID-19 pneumonia, regardless of whether he underwent fibrinolysis. It is therefore important to consider that if this patient did not contract COVID-19 pneumonia, he still had many risk factors that made him prone to ischaemic stroke formation. Thus, we must consider whether similar patients would suffer from ischaemic stroke, regardless of COVID-19 infection and whether COVID-19 impacts on the severity of the stroke as an entity.

Having said this, the management of these patients is dependent on the likelihood of a positive outcome from the COVID-19 infection. Establishing the ceiling of care is crucial, as it prevents incredibly unwell or unfit patients’ from going through futile treatments, ensuring respect and dignity in death, if this is the likely outcome. It also allows for the provision of limited or intensive resources, such as intensive care beds or endotracheal intubation during the COVID-19 pandemic, to those who are assessed by the multidisciplinary team to benefit the most from their use. The way to establish this ceiling of care is through an early multidisciplinary discussion. In this case, the patient did not convey his wishes regarding his care to the medical team or his family; therefore it was decided among intensive care specialists, respiratory physicians, stroke physicians and the patients’ relatives. The patient was discussed with the intensive care team, who decided that as the patient sustained two acute life-threatening illnesses simultaneously and had rapidly deteriorated, ward-based care with a view to palliate if the further deterioration was in the patients’ best interests. These decisions were not easy to make, especially as it was on the first day of presentation. This decision was made in the context of the patients’ comorbidities, including COPD, the patients’ age, and the availability of intensive care beds during the steep rise in intensive care admissions, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic ( figure 1 ). Furthermore, the patients’ rapid and permanent decline in GCS, entwined with the severe stroke on CT imaging of the brain made it more unlikely that significant and permanent recovery could be achieved from mechanical intubation, especially as the damage caused by the stroke could not be significantly reversed. As hospitals manage patients with COVID-19 in many parts of the world, there may be tension between the need to provide higher levels of care for an individual patient and the need to preserve finite resources to maximise the benefits for most patients. This patient presented during a steep rise in intensive care admissions, which may have influenced the early decision not to treat the patient in an intensive care setting. Retrospective studies from Wuhan investigating mortality in patients with multiple organ failure, in the setting of COVID-19, requiring intubation have demonstrated mortality can be up to 61.5%. 17 The mortality risk is even higher in those over 65 years of age with respiratory comorbidities, indicating why this patient was unlikely to survive an admission to the intensive care unit. 18

Regularly updating the patients’ family ensured cooperation, empathy and sympathy. The patients’ stroke was not seen as a priority given the severity of his COVID-19 pneumonia, therefore the least invasive, but most appropriate treatment was provided for his stroke. The British Association of Stroke Physicians advocate this approach and also request the notification to their organisation of COVID-19-related stroke cases, in the UK. 19

Learning points

- SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2) is one of seven known coronaviruses that commonly cause upper and lower respiratory tract infections. It is the cause of the 2019–2020 global coronavirus pandemic.

- The significance of COVID-19 is illustrated by the rapid speed of its spread globally and the potential to cause severe clinical presentations, such as ischaemic stroke.

- Early retrospective data has indicated that up to 36% of COVID-19 patients had neurological manifestations, including stroke.

- Potential mechanisms behind stroke in COVID-19 patients include a plethora of hypercoagulability secondary to critical illness and systemic inflammation, the development of arrhythmia, alteration to the vascular endothelium resulting in atherosclerotic plaque displacement and dehydration.

- It is vital that effective, open communication between the multidisciplinary team, patient and patients relatives is conducted early in order to firmly establish the most appropriate ceiling of care for the patient.

Contributors: SB was involved in the collecting of information for the case, the initial written draft of the case and researching existing data on acute stroke and COVID-19. He also edited drafts of the report. MH was involved in reviewing and editing drafts of the report and contributing new data. SP oversaw the conduction of the project and contributed addition research papers.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Next of kin consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Open access

- Published: 09 September 2024

Stroke after heart valve surgery: a single center institution report

- Nizar Alwaqfi 1 ,

- Majd M. AlBarakat 1 ,

- Hala Qariouti 1 ,

- Khalid Ibrahim 1 &

- Nabil alzoubi 1

Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery volume 19 , Article number: 518 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Introduction

Stroke is a potentially debilitating complication of heart valve replacement surgery, with rates ranging from 1 to 10%. Despite advancements in surgical techniques, the incidence of postoperative stroke remains a significant concern, impacting patient outcomes and healthcare resources. This study aims to investigate the incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of in-hospital adverse neurologic events, particularly stroke, following valve replacement. The analysis focuses on identifying patient characteristics and procedural factors associated with increased stroke risk.

This retrospective study involves a review of 417 consecutive patients who underwent SVR between January 2004 and December 2022. The study cohort was extracted from a prospectively recorded cardiac intensive care unit database. Preoperative and perioperative data were collected, and subjects with specific exclusion criteria were omitted from the analysis. The analysis includes demographic information, preoperative risk factors, and perioperative variables.

The study identified a 4.3% incidence of postoperative stroke among SVR patients. Risk factors associated with increased stroke susceptibility included prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass time, aortic cross-clamp duration exceeding 90 min, prior stroke history, diabetes mellitus, and mitral valve annulus calcification. Patients undergoing combined procedures, such as aortic valve replacement with mitral valve replacement or coronary artery bypass grafting with AVR and MVR, (OR = 10.74, CI:2.65–43.44, p-value = < 0.001) and (OR = 11.66, CI:1.02–132.70, p-value = 0.048) respectively, exhibited elevated risks. Internal carotid artery stenosis (< 75%) and requiring prolonged inotropic support were also associated with increased stroke risk(OR = 3.04, CI:1.13–8.12, P-value = 0.026). The occurrence of stroke correlated with extended intensive care unit stay (OR = 1.12, CI: 1.04–1.20, P-value = 0.002) and heightened in-hospital mortality.

In conclusion, our study identifies key risk factors and underscores the importance of proactive measures to reduce postoperative stroke incidence in surgical valve replacement patients.

Peer Review reports

Stroke is a rare but still a potentially crippling complication of heart valve replacement surgery with risk dependent on patient characteristics and concomitant procedures. Stroke rates after surgical valve replacement (SVR) have ranged widely from 1 to 10% [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ].

Studies of clinical stroke-complicating cardiac surgeries have reported increased duration and cost of hospitalization, dramatically elevated in-hospital mortality, and a high rate of severe disability in survivors [ 4 , 8 , 9 ].

Several studies have evaluated risk factors and postoperative neurologic complications after heart valve surgery, though the results are conflicting or incomplete mainly due to a low number of interventions or a low number of variables. Also, the low incidence of this postoperative key event limits the power of most published papers. Some studies have reported the association between prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and the development of postoperative stroke, while others have questioned its significance [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Other reported risk factors include age, concomitant atrial fibrillation (AF), history of cerebrovascular (CV) disease, concomitant carotid artery (CA) stenosis and aortic atherosclerosis, preoperative left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, concomitant procedures and lack of postoperative anticoagulation. [ 10 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ] Recently, there is evidence that the rate of neurologic complications after SVR has been increasing, likely because of the willingness of surgeons to operate on older and higher-risk patients. [ 1 , 16 ] As such the current literature provides heterogeneous rates of adverse in-hospital neurologic complications after SVR. This heterogeneity, especially from the clinical trials, has raised the issue of whether the real-life stroke rate after heart valve surgery is different from that in the trial setting.

To address this issue and to the best of our knowledge, in our institution, stroke incidence, risk factors, and outcomes were not reported. We aimed to assess the incidence of in-hospital adverse neurologic events after SVR (with or without coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]) and to identify patient and disease factors associated with stroke. In addition, the impact of postoperative stroke on length of hospital stay (LOS) and in-hospital mortality was evaluated.

Materials and methods

This study is a retrospective review of the clinical, operative, and outcome data that is part of the prospectively recorded cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) database. The present analysis includes all replacement valve surgeries performed between January 2004 and December 2022. Preoperative and perioperative data were retrospectively collected. After isolation of data, subjects were excluded if they had undergone CA stenting or endarterectomy within the previous 6 weeks; had any significant neurological disease, defined as the incidence of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) within the preceding 6 months; had symptomatic or asymptomatic severe occlusive CA disease requiring concomitant endarterectomy/stenting. Also, patients who underwent valve repair, additional procedures on the aorta, and redo valve surgery were excluded from the study. Additionally, patients were excluded if an additional surgical procedure on the ascending aorta was performed.

The studied population consisted of 417 consecutive patients. Two groups were identified; Group 1 consisted of 18 patients who had a postoperative stroke, and group 2 consisted of the remaining patients (399) in the cohort. This work was approved by the ethical committee in the institution and the patient`s signature was waived.

Preoperative data

Patient’s medical records were reviewed for prior stroke; results of brain computerized tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), when available, or presence of unresolved neurological deficit, body mass index (BMI), New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification; symptomatic patients or on anti-failure treatment, diabetes mellitus (DM); with the majority being type 2 diabetes managed with oral hypoglycemic agents, hypertension; previously diagnosed and on anti-hypertensive treatment, chronic renal impairment (CRI); creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/dl or on chronic dialysis, peripheral vascular disease (PVD); positive history of intermittent claudication or a documented clinical evidence of peripheral ischemia, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF); by either angiography or echocardiography, number of diseased coronary arteries; based on coronary angiogram and operative reports.

CA duplex scanning or CT scan angiography was performed routinely for most of the patients (80% of the studied cohort); almost 8% had severe CA stenosis (luminal narrowing ≥ 75%) and 24.5% had moderate disease. Patients with severe CA stenosis were sent for surgical or percutaneous intervention before valve surgery.

Perioperative antithrombotic treatment

Patients who were taking aspirin (100 mg) continued this medication without interruption preoperatively. Heparin (3.0 mg/kg) was administered intravenously before cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) to maintain an activated clotting time (ACT) greater than 400 s. At the end of the procedure, heparin was neutralized with protamine sulfate (3.0 mg/kg). Additional protamine was administered if ACT remained above 140 s before chest closure. Neither aprotinin nor tranexamic acid was used in any patient. Transfusion of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets was determined based on bleeding volume, International Normalized Ratio (INR) levels, and platelet counts.

Postoperatively, patients received warfarin with bridging using unfractionated heparin or enoxaparin until the INR reached therapeutic levels. The target INR was 2.5 to 3 times normal for patients with St. Jude, Carbomedics, or Medtronic Hall aortic valves, and 3 to 3.5 times normal for patients with St. Jude, Carbomedics, or Medtronic Hall mitral valves. Patients with more than one prosthetic valve were maintained at a target INR of 3.5 to 4 times normal. The addition of daily aspirin (100 mg) was at the discretion of the treating physician.

Patients with bioprosthetic valves received warfarin for 1 to 3 months postoperatively, followed by lifelong aspirin therapy. In patients with bioprosthetic valves and atrial fibrillation, warfarin was continued as clinically indicated.

Intraoperative data

Assessment of the ascending aorta was performed using digital palpation. It is noted that none of the stroke patients included in this study had documented atherosclerotic disease of the ascending aorta; therefore, this variable was not specifically assessed.

Standard techniques were employed for cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), ensuring perfusion was maintained at 2.0 to 2.4 L/min/m². Systemic perfusion pressure was carefully regulated within the range of 60 to 80 mmHg throughout the procedure. Myocardial viability was preserved through the use of cold antegrade potassium cardioplegia and topical hypothermia techniques. Furthermore, body temperature was meticulously controlled and maintained between 28 °C and 32 °C to optimize surgical conditions and patient outcomes.

Neurological complications

Stroke was defined as any new focal neurological dysfunction of presumed vascular origin lasting more than 24 h. A neurological assessment is routinely done by the surgical team if patients are extubated within 24 h. Patients with positive neurological examination, suspected neurological deficit, and/or prolonged time on ventilator are usually assessed by the neurologists. Stroke diagnosis was based on clinical findings and brain imaging by CT scan or MRI.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as either mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range], depending on the distribution normality. Categorical variables are displayed as counts (percentages). Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for categorical data comparisons. A p-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 3.4.0, R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

Table 1 displays the demographics and univariate analyses of patient characteristics in groups 1 (stroke) and 2 (no stroke). There were 17 (4.3%) patients in group 1 and 399 patients in group 2. The average age for group 1 was 59.5 (± 9.44) years, whereas for group 2 it was 51.6 (± 15.3) years, yielding a statistically significant difference ( p = 0.003). The mean BMI for group 1 was 28.8 (± 4.36), while for group 2 it was 22.0 (± 5.1%).

Approximately 44.4% of patients in the postoperative stroke group exhibited mitral valve annulus calcification (MVAC), whereas this figure was only 17% in the other group. Additionally, 50% of the patients with stroke had DM, in contrast to only 20% in the other group. The most prevalent type of operation in the stroke group was AVR combined with MVR, whereas in the other group, AVR alone was the predominant procedure.

Table 2 . presents the Crude Odds Ratios (OR) and their corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for factors associated with postoperative Stroke. Patients undergoing procedures such as AVR with MVR, MVR with CABG, and AVR with MVR and CABG exhibited elevated risks of postoperative stroke, with odds ratios of 10, 5, and 11 respectively.

Patients with internal CA stenosis ranging from 50% to less than 75% demonstrated a substantially increased susceptibility to stroke, with an odds ratio of 4.129 (CI: 1.3887–12.2761) and a p-value of 0.011. Similarly, individuals with DM were associated with a heightened risk, displaying an odds ratio of 3.9259 (CI: 1.5098–10.2082) and a p-value of 0.005.

Patients with a prior history of stroke exhibited a higher risk with an odds ratio of 4.4643 and a CI of (1.3645–14.6064), with a p-value of 0.013. Furthermore, CPB exceeding 120 min demonstrated a significantly elevated risk in comparison to durations less than 120 min, with an odds ratio of 6.312 and a CI of 0.4631–9.9076 ( p < 0.001). Additionally, aortic cross-clamping for more than 90 min demonstrated a heightened risk with an odds ratio of 6.2661 and a CI of 2.3546–16.6754, with a p-value less than 0.001.

Patients requiring prolonged inotropic support for more than 48 h demonstrated a significantly increased risk, with an odds ratio of 3.04 (95% CI: 1.14–8.13) and a p-value of 0.026. Furthermore, the occurrence of stroke was associated with an extended stay in the CICU, indicated by an odds ratio of 1.12 (95% CI: 1.04–1.20) and a p-value of 0.002.

The stroke group exhibited a significantly elevated postoperative mortality risk, with an OR of 7.05 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.78–27.95), indicating a substantial increase in risk. The corresponding p-value was 0.005.

In our study, we assessed the occurrence of postoperative stroke in 417 consecutive SVR patients which included different valve replacement and combined surgeries. We found that 4.3% of patients experienced postoperative stroke, matching what was reported by Raffa et al. [ 23 ] with a sample size of 2121 patients. This drastic complication was significantly associated with prolonged CICU stay and increased operative mortality, this association was clearly established in our analysis, underscoring the importance of identifying potential risk factors to mitigate postoperative neurological complications. The exact reason for this high mortality associated with stroke remains unclear. We think most of stroke patients are elderly with multiple comorbidities, spend long time in CICU on ventilator, which make them prone for major complications, particularly respiratory failure and sepsis. [ 10 , 18 ]