Scientific Method

Server costs fundraiser 2024.

The Scientific Method was first used during the Scientific Revolution (1500-1700). The method combined theoretical knowledge such as mathematics with practical experimentation using scientific instruments, results analysis and comparisons, and finally peer reviews, all to better determine how the world around us works. In this way, hypotheses were rigorously tested, and laws could be formulated which explained observable phenomena. The goal of this scientific method was to not only increase human knowledge but to do so in a way that practically benefitted everyone and improved the human condition.

A New Approach: Bacon 's Vision

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) was an English philosopher, statesman, and author. He is considered one of the founders of modern scientific research and scientific method, even as "the father of modern science " because he proposed a new combined method of empirical (observable) experimentation and shared data collection so that humanity might finally discover all of nature's secrets and improve itself. Bacon championed the need for systematic and detailed empirical study, as this was the only way to increase humanity's understanding and, for him, more importantly, gain control of nature. This approach sounds quite obvious today, but at the time, the highly theoretical approach of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE) still dominated thought. Verbal arguments had become more important than what could actually be seen in the world. Further, natural philosophers had become preoccupied with why things happen instead of first ascertaining what was happening in nature.

Bacon rejected the current backward-looking approach to knowledge, that is, the seemingly never-ending attempt to prove the ancients right. Instead, new thinkers and experimenters, said Bacon, should act like the new navigators who had pushed beyond the limits of the known world. Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) had shown there was land across the Atlantic Ocean. Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) had explored the globe in the other direction. Scientists, as we would call them today, had to be similarly bold. Old knowledge had to be rigorously tested to see that it was worth keeping. New knowledge had to be acquired by thoroughly testing nature without preconceived ideas. Reason had to be applied to data collected from experiments, and the same data had to be openly shared with other thinkers so that it could be tested again, comparing it to what others had discovered. Finally, this knowledge must then be used to improve the human condition; otherwise, it was no use pursuing it in the first place. This was Bacon's vision. What he proposed did indeed come about but with three notable factors added to the scientific method. These were mathematics, hypotheses, and technology.

The Importance of Experiments & Instruments

Experiments had always been carried out by thinkers, from ancient figures like Archimedes (l. 287-212 BCE) to the alchemists of the Middle Ages, but their experiments were usually haphazard, and very often thinkers were trying to prove a preconceived idea. In the Scientific Revolution, experimentation became a more systematic and multi-layered activity involving many different people. This more rigorous approach to gathering observable data was also a reaction against traditional activities and methods such as magic, astrology, and alchemy , all ancient and secret worlds of knowledge-gathering that now came under attack.

At the outset of the Scientific Revolution, experiments were any sort of activity carried out to see what would happen, a sort of anything-goes approach to satisfying scientific curiosity. It is important to note, though, that the modern meaning of scientific experiment is rather different, summarised here by W. E. Burns: "the creation of an artificial situation designed to study scientific principles held to apply in all situations" (95). It is fair to say, though, that the modern approach to experimentation, with its highly specialised focus where only one specific hypothesis is being tested, would not have become possible without the pioneering experimenters of the Scientific Revolution.

The first well-documented practical experiment of our period was made by William Gilbert using magnets; he published his findings in 1600 in On the Magnet . The work was pioneering because "Central to Gilbert's enterprise was the claim that you could reproduce his experiments and confirm his results: his book was, in effect, a collection of experimental recipes" (Wootton, 331).

There remained sceptics of experimentation, those who stressed that the senses could be misled when the reason of the mind could not be. One such doubter was René Descartes (1596-1650), but if anything, he and other natural philosophers who questioned the value of the work of the practical experimenters were responsible for creating a lasting new division between philosophy and what we would today call science. The term "science" was still not widely used in the 17th century, instead, many experimenters referred to themselves as practitioners of "experimental philosophy". The first use in English of the term "experimental method" was in 1675.

The first truly international effort in coordinated experiments involved the development of the barometer. This process began with the efforts of the Italian Evangelista Torricelli (1608-1647) in 1643. Torricelli discovered that mercury could be raised within a glass tube when one end of that tube was placed in a container of mercury. The air pressure on the mercury in the container pushed the mercury in the tube up around 30 inches (76 cm) higher than the level in the container. In 1648, Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) and his brother-in- law Florin Périer conducted experiments using similar apparatus, but this time tested under different atmospheric pressures by setting up the devices at a variety of altitudes on the side of a mountain. The scientists noted that the level of the mercury in the glass tube fell the higher up the mountain readings were taken.

The Anglo-Irish chemist Robert Boyle (1627-1691) named the new instrument a barometer and conclusively demonstrated the effect of air pressure by using a barometer inside an air pump where a vacuum was established. Boyle formulated a principle which became known as 'Boyle's Law'. This law states that the pressure exerted by a certain quantity of air varies inversely in proportion to its volume (provided temperatures are constant). The story of the development of the barometer became typical throughout the Scientific Revolution: natural phenomena were observed, instruments were invented to measure and understand these observable facts, scientists collaborated (sometimes even competed), and so they extended the work of each other until, finally, a universal law could be devised which explained what was being seen. This law could then be used as a predictive device in future experiments.

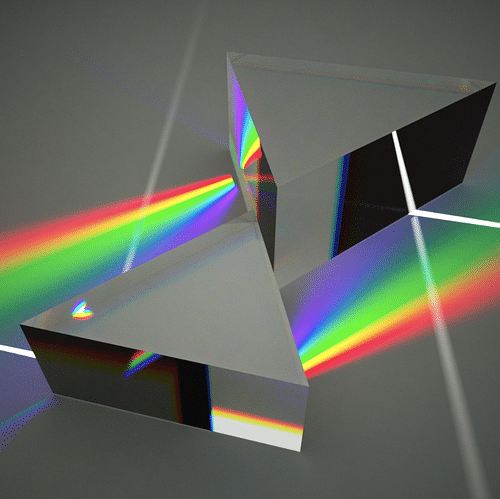

Experiments like Robert Boyle's air pump demonstrations and Isaac Newton 's use of a prism to demonstrate white light is made up of different coloured light continued the trend of experimentation to prove, test, and adjust theories. Further, these endeavours highlight the importance of scientific instruments in the new method of inquiry. The scientific method was employed to invent useful and accurate instruments, which were, in turn, used in further experiments. The invention of the telescope (c. 1608), microscope (c. 1610), barometer (1643), thermometer (c. 1650), pendulum clock (1657), air pump (1659), and balance spring watch (1675) all allowed fine measurements to be made which previously had been impossible. New instruments meant that a whole new range of experiments could be carried out. Whole new specialisations of study became possible, such as meteorology, microscopic anatomy, embryology, and optics.

The scientific method came to involve the following key components:

- conducting practical experiments

- conducting experiments without prejudice of what they should prove

- using deductive reasoning (creating a generalisation from specific examples) to form a hypothesis (untested theory), which is then tested by an experiment, after which the hypothesis might be accepted, altered, or rejected based on empirical (observable) evidence

- conducting multiple experiments and doing so in different places and by different people to confirm the reliability of the results

- an open and critical review of the results of an experiment by peers

- the formulation of universal laws (inductive reasoning or logic) using, for example, mathematics

- a desire to gain practical benefits from scientific experiments and a belief in the idea of scientific progress

(Note: the above criteria are expressed in modern linguistic terms, not necessarily those terms 17th-century scientists would have used since the revolution in science also caused a revolution in the language to describe it).

Scientific Institutions

The scientific method really took hold when it became institutionalised, that is, when it was endorsed and employed by official institutions like the learned societies where thinkers tested their theories in the real world and worked collaboratively. The first such society was the Academia del Cimento in Florence, founded in 1657. Others soon followed, notably the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris in 1667. Four years earlier, London had gained its own academy with the foundation of the Royal Society . The founding fellows of this society credited Bacon with the idea, and they were keen to follow his principles of scientific method and his emphasis on sharing and communicating scientific data and results. The Berlin Academy was founded in 1700 and the St. Petersburg Academy in 1724. These academies and societies became the focal points of an international network of scientists who corresponded, read each other's works, and even visited each other as the new scientific method took hold.

Official bodies were able to fund expensive experiments and assemble or commission new equipment. They showed these experiments to the public, a practice that illustrates that what was new here was not the act of discovery but the creation of a culture of discovery. Scientists went much further than a real-time audience and ensured their results were printed for a far wider (and more critical) readership in journals and books. Here, in print, the experiments were described in great detail, and the results were presented for all to see. In this way, scientists were able to create "virtual witnesses" to their experiments. Now, anyone who cared to be could become a participant in the development of knowledge acquired through science.

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Burns, William E. The Scientific Revolution in Global Perspective. Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Burns, William E. The Scientific Revolution. ABC-CLIO, 2001.

- Bynum, William F. & Browne, Janet & Porter, Roy. Dictionary of the History of Science . Princeton University Press, 1982.

- Henry, John. The Scientific Revolution and the Origins of Modern Science . Red Globe Press, 2008.

- Jardine, Lisa. Ingenious Pursuits. Nan A. Talese, 1999.

- Moran, Bruce T. Distilling Knowledge. Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Wootton, David. The Invention of Science. Harper, 2015.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Questions & Answers

What are the different steps of the scientific method, what was the scientific method in the scientific revolution, related content.

Scientific Revolution

Ancient Greek Science

The Scientific Revolution

Women Scientists in the Scientific Revolution

6 Key Instruments of the Scientific Revolution

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

Cite This Work

Cartwright, M. (2023, November 07). Scientific Method . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/Scientific_Method/

Chicago Style

Cartwright, Mark. " Scientific Method ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified November 07, 2023. https://www.worldhistory.org/Scientific_Method/.

Cartwright, Mark. " Scientific Method ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 07 Nov 2023. Web. 30 Aug 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Mark Cartwright , published on 07 November 2023. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

Presidential Column

The tradition of experimentalism in psychology.

- Experimental

- History of Psychology

- John Darley Columns

It sometimes makes sense to examine a discipline in terms of what I am tempted to call its “tribal customs.” By this I mean its habitual, frequently unexamined, ways of doing its everyday activities and communicating about the results of those activities both to itself and to adjacent tribes. Continuing the metaphor, it is useful to compare the customs of psychology with scientifically adjacent tribes such as sociology, cognitive science, and anthropology, and even more distant tribes such as literary criticism and philosophy.

One reason for this sort of examination is celebratory – to revel in the superiority of the customs of our discipline over those of the adjacent disciplines. Once that is completed to the satisfaction of all, and the moral and intellectual superiority of our ways demonstrated to all of open mind, then it is possible to grudgingly consider whether a thing or two might be learned or a practice or two adopted from the competition.

I propose to go forward exactly in this vein, coming to the conclusion that scientific psychology is in good order, and that its everyday practices and ideological commitments to ways of doing things are generally contributing to its strengths. But I will manage to discover some difficulties, artfully casting them as the reverse side of our strengths, and see whether some friendly amendments to our customs might not be worth considering. In this month’s column, I will explore the strengths of our traditions, in the next months we will see how those traditions might be limiting us.

The central field of psychology, the one that set the paradigm to which we all aspired, has been “experimental psychology.” The remarkable fact here is that it was seldom necessary to specify what processes the experimentation was about; we were just “experimentalists.” The topics on which we were experimenting differed over time, but our commitment to the experiment as the preferred technique for unlocking the secrets of the universe has been constant.

We were able to privilege experimentation because of the derivations that followed from another tenet of our ideology, which was that our task was to discover the universal laws of learning, or of perception, or of reasoning. The ways in which experimentation could strip down a complicated, messy situation to its apparent essence fit well with an emphasis on the project of discovering the universals of process.

With those universal processes in hand, we could then understand the complexities of, for instance, college students learning, experienced pilots perceiving, or experts reasoning. The laws of learning could be discovered by experimentation on infra-human species, and of memory by having subjects – people this time – learn nonsense syllables, and so on.

Other fields of psychology looked at problems that were less tractable to an experimental approach – or seemed so. But triumphs could be achieved by bringing the experimental method to those fields; many readers will remember the stir caused by Leon Festinger’s first set of dissonance experiments, exactly because they demonstrated that it was possible to do experiments in a field in which they had not previously seemed possible. (Lewin carried out several studies that are broadly referred to as “experimental,” but looked back on don’t support that claim very well.)

And it is useful to remember that Festinger, who had a remarkably broad competitive streak, chose a reinforcement theory as the one he would challenge in those experiments. Reinforcement theory at that time was the paradigmatic center of the search for universals in psychology and so in challenging it, one announced the arrival of a new kid on the block, ready to challenge the system. But and again, the challenge was carried out by experimentation. In personality psychology, a number of scales of single constructs were designed, and validated by a procedure that resembled experimentation; groups of individuals who scored high or low on a particular personality construct were put through, for instance, an experimental procedure that measured conformity-proneness.

Ideological elements intertwine and support each other. Our preference for the experimental method fit well with our emphasis on the analysis of causality. (As introductory textbooks often proclaim, experimentation is the one method that can unequivocally establish causality.) And of course we were aware of the difficulties attendant on other modes of inference. We were aware, for instance, of the demonstrations that introspection gave a rather poor account of perceptual phenomena.

For me the power of experimentation to identify cause with immediate lucidity was learned in my undergraduate laboratory courses with Hans Wallach, who gently led us to hypotheses we could test about Gestalt perceptual phenomena. And when we had the hypothesis right, and the experiment properly designed, we could instantly see which stimulus alterations controlled the perceptual phenomena. I have talked to many other psychological researchers and it is amazing the frequency with which some similar story of discovering the joys of doing clean experimental designs in the laboratory of a beloved mentor is the life-altering event that led to our career choice.

So our program, to sum it up, involved discovering through experimentation, the basic laws of human functioning, laws that would identify the true causal events in a confused world of multiple possibilities. The laws would be universals, would transcend differences among persons brought about by culture or upbringing, would transcend the multiple differences brought about by the details of the contexts in which people existed. And we have the intellectual characteristics that are the internal representations of that program. We insist on clear causal thinking, we are skeptical about unproven (that is, experimentally untested) claims, and we scorn those whose theories seem to be nothing but long lists of complex and underspecified assertions. Metaphorically, psychologists pride themselves on being from Missouri.

This ideological program, or paradigm to stray into Kuhnian terms, has stood us in good stead. That is, it has led us to some remarkable and important discoveries. Anyone concerned with learning who ignores the far reaching discoveries of reinforcement theory is making a serious mistake. And we have outlined the workings of the perceptual system, and are now making important discoveries about the ways in which sensory and motor information are merged in the cortex. From judgment and decision making research we have prospect theory, and a bias- and heuristic-driven account of human decision making. Using priming and response latency measurement techniques, and the power of modern computers, we have made some fascinating discoveries about cognitive associationistic structures and their workings, and on the ways in which the mind represents information, events, and perceptions of people.

The paradigm has also protected us from what many would now consider fads and excesses. To say that the post-modernist perspective, that all “readings of a situation,” all interpretations of an event, have equal validity (or perhaps equally no validity) had little influence on psychology is putting it mildly. Even though we hold that many aspects of an individual’s view of the world are social constructions, we hold that those constructions are determined by causal circumstances, and constrained by the external realities of both the physical and the social worlds. And our commitment to experimentation as revealing causal truth has made us a far too rocky soil for notions of science being merely another cultural ritual, similar to augurs consulting chicken entrails or astrological signs to determine “truth,” to take root. Compared to some other sciences, psychologists have spent little time in these debates and that seems to me to be on balance to be a good thing.

Each reader will have many more examples to add to a list of successes our scientific ideology has brought about, and the excesses it has allowed us to avoid. So with the security of “a job well done,” it might now make some sense to consider what limits or difficulties the adherence to what we might call the causal/experimental paradigm has visited on us. Next column, I will make some suggestions about that.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

Economic Field Experiments Complement Understanding of Judgment Bias

Field experiments in economics can serve an invaluable intellectual role alongside traditional laboratory research.

Beilock Receives National Academy of Sciences Troland Research Award

The National Academy of Sciences has announced that APS Fellow Sian L. Beilock is a recipient of the 2017 Troland Research Award. The $75,000 prize is awarded to young investigators in recognition of outstanding scientific

Three Mediation Stories, Three Analytic Strategies

In recognition of APS’s forthcoming journal on methodological advances, APS President Susan Goldin-Meadow invites her University of Chicago colleagues Stephen Raudenbush and Guanglei Hong to discuss a new view of path analysis that they hope will find its way into all areas of psychological science.

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELBCORS | 5 minutes | This cookie is used by Elastic Load Balancing from Amazon Web Services to effectively balance load on the servers. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| at-rand | never | AddThis sets this cookie to track page visits, sources of traffic and share counts. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| uvc | 1 year 27 days | Set by addthis.com to determine the usage of addthis.com service. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_3507334_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| loc | 1 year 27 days | AddThis sets this geolocation cookie to help understand the location of users who share the information. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

experimental psychology

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- American Psychological Association - Understanding Experimental Psychology

experimental psychology , a method of studying psychological phenomena and processes. The experimental method in psychology attempts to account for the activities of animals (including humans) and the functional organization of mental processes by manipulating variables that may give rise to behaviour; it is primarily concerned with discovering laws that describe manipulable relationships. The term generally connotes all areas of psychology that use the experimental method.

These areas include the study of sensation and perception , learning and memory , motivation , and biological psychology . There are experimental branches in many other areas, however, including child psychology , clinical psychology , educational psychology , and social psychology . Usually the experimental psychologist deals with normal, intact organisms; in biological psychology, however, studies are often conducted with organisms modified by surgery, radiation, drug treatment, or long-standing deprivations of various kinds or with organisms that naturally present organic abnormalities or emotional disorders. See also psychophysics .

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How the Experimental Method Works in Psychology

sturti/Getty Images

The Experimental Process

Types of experiments, potential pitfalls of the experimental method.

The experimental method is a type of research procedure that involves manipulating variables to determine if there is a cause-and-effect relationship. The results obtained through the experimental method are useful but do not prove with 100% certainty that a singular cause always creates a specific effect. Instead, they show the probability that a cause will or will not lead to a particular effect.

At a Glance

While there are many different research techniques available, the experimental method allows researchers to look at cause-and-effect relationships. Using the experimental method, researchers randomly assign participants to a control or experimental group and manipulate levels of an independent variable. If changes in the independent variable lead to changes in the dependent variable, it indicates there is likely a causal relationship between them.

What Is the Experimental Method in Psychology?

The experimental method involves manipulating one variable to determine if this causes changes in another variable. This method relies on controlled research methods and random assignment of study subjects to test a hypothesis.

For example, researchers may want to learn how different visual patterns may impact our perception. Or they might wonder whether certain actions can improve memory . Experiments are conducted on many behavioral topics, including:

The scientific method forms the basis of the experimental method. This is a process used to determine the relationship between two variables—in this case, to explain human behavior .

Positivism is also important in the experimental method. It refers to factual knowledge that is obtained through observation, which is considered to be trustworthy.

When using the experimental method, researchers first identify and define key variables. Then they formulate a hypothesis, manipulate the variables, and collect data on the results. Unrelated or irrelevant variables are carefully controlled to minimize the potential impact on the experiment outcome.

History of the Experimental Method

The idea of using experiments to better understand human psychology began toward the end of the nineteenth century. Wilhelm Wundt established the first formal laboratory in 1879.

Wundt is often called the father of experimental psychology. He believed that experiments could help explain how psychology works, and used this approach to study consciousness .

Wundt coined the term "physiological psychology." This is a hybrid of physiology and psychology, or how the body affects the brain.

Other early contributors to the development and evolution of experimental psychology as we know it today include:

- Gustav Fechner (1801-1887), who helped develop procedures for measuring sensations according to the size of the stimulus

- Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-1894), who analyzed philosophical assumptions through research in an attempt to arrive at scientific conclusions

- Franz Brentano (1838-1917), who called for a combination of first-person and third-person research methods when studying psychology

- Georg Elias Müller (1850-1934), who performed an early experiment on attitude which involved the sensory discrimination of weights and revealed how anticipation can affect this discrimination

Key Terms to Know

To understand how the experimental method works, it is important to know some key terms.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is the effect that the experimenter is measuring. If a researcher was investigating how sleep influences test scores, for example, the test scores would be the dependent variable.

Independent Variable

The independent variable is the variable that the experimenter manipulates. In the previous example, the amount of sleep an individual gets would be the independent variable.

A hypothesis is a tentative statement or a guess about the possible relationship between two or more variables. In looking at how sleep influences test scores, the researcher might hypothesize that people who get more sleep will perform better on a math test the following day. The purpose of the experiment, then, is to either support or reject this hypothesis.

Operational definitions are necessary when performing an experiment. When we say that something is an independent or dependent variable, we must have a very clear and specific definition of the meaning and scope of that variable.

Extraneous Variables

Extraneous variables are other variables that may also affect the outcome of an experiment. Types of extraneous variables include participant variables, situational variables, demand characteristics, and experimenter effects. In some cases, researchers can take steps to control for extraneous variables.

Demand Characteristics

Demand characteristics are subtle hints that indicate what an experimenter is hoping to find in a psychology experiment. This can sometimes cause participants to alter their behavior, which can affect the results of the experiment.

Intervening Variables

Intervening variables are factors that can affect the relationship between two other variables.

Confounding Variables

Confounding variables are variables that can affect the dependent variable, but that experimenters cannot control for. Confounding variables can make it difficult to determine if the effect was due to changes in the independent variable or if the confounding variable may have played a role.

Psychologists, like other scientists, use the scientific method when conducting an experiment. The scientific method is a set of procedures and principles that guide how scientists develop research questions, collect data, and come to conclusions.

The five basic steps of the experimental process are:

- Identifying a problem to study

- Devising the research protocol

- Conducting the experiment

- Analyzing the data collected

- Sharing the findings (usually in writing or via presentation)

Most psychology students are expected to use the experimental method at some point in their academic careers. Learning how to conduct an experiment is important to understanding how psychologists prove and disprove theories in this field.

There are a few different types of experiments that researchers might use when studying psychology. Each has pros and cons depending on the participants being studied, the hypothesis, and the resources available to conduct the research.

Lab Experiments

Lab experiments are common in psychology because they allow experimenters more control over the variables. These experiments can also be easier for other researchers to replicate. The drawback of this research type is that what takes place in a lab is not always what takes place in the real world.

Field Experiments

Sometimes researchers opt to conduct their experiments in the field. For example, a social psychologist interested in researching prosocial behavior might have a person pretend to faint and observe how long it takes onlookers to respond.

This type of experiment can be a great way to see behavioral responses in realistic settings. But it is more difficult for researchers to control the many variables existing in these settings that could potentially influence the experiment's results.

Quasi-Experiments

While lab experiments are known as true experiments, researchers can also utilize a quasi-experiment. Quasi-experiments are often referred to as natural experiments because the researchers do not have true control over the independent variable.

A researcher looking at personality differences and birth order, for example, is not able to manipulate the independent variable in the situation (personality traits). Participants also cannot be randomly assigned because they naturally fall into pre-existing groups based on their birth order.

So why would a researcher use a quasi-experiment? This is a good choice in situations where scientists are interested in studying phenomena in natural, real-world settings. It's also beneficial if there are limits on research funds or time.

Field experiments can be either quasi-experiments or true experiments.

Examples of the Experimental Method in Use

The experimental method can provide insight into human thoughts and behaviors, Researchers use experiments to study many aspects of psychology.

A 2019 study investigated whether splitting attention between electronic devices and classroom lectures had an effect on college students' learning abilities. It found that dividing attention between these two mediums did not affect lecture comprehension. However, it did impact long-term retention of the lecture information, which affected students' exam performance.

An experiment used participants' eye movements and electroencephalogram (EEG) data to better understand cognitive processing differences between experts and novices. It found that experts had higher power in their theta brain waves than novices, suggesting that they also had a higher cognitive load.

A study looked at whether chatting online with a computer via a chatbot changed the positive effects of emotional disclosure often received when talking with an actual human. It found that the effects were the same in both cases.

One experimental study evaluated whether exercise timing impacts information recall. It found that engaging in exercise prior to performing a memory task helped improve participants' short-term memory abilities.

Sometimes researchers use the experimental method to get a bigger-picture view of psychological behaviors and impacts. For example, one 2018 study examined several lab experiments to learn more about the impact of various environmental factors on building occupant perceptions.

A 2020 study set out to determine the role that sensation-seeking plays in political violence. This research found that sensation-seeking individuals have a higher propensity for engaging in political violence. It also found that providing access to a more peaceful, yet still exciting political group helps reduce this effect.

While the experimental method can be a valuable tool for learning more about psychology and its impacts, it also comes with a few pitfalls.

Experiments may produce artificial results, which are difficult to apply to real-world situations. Similarly, researcher bias can impact the data collected. Results may not be able to be reproduced, meaning the results have low reliability .

Since humans are unpredictable and their behavior can be subjective, it can be hard to measure responses in an experiment. In addition, political pressure may alter the results. The subjects may not be a good representation of the population, or groups used may not be comparable.

And finally, since researchers are human too, results may be degraded due to human error.

What This Means For You

Every psychological research method has its pros and cons. The experimental method can help establish cause and effect, and it's also beneficial when research funds are limited or time is of the essence.

At the same time, it's essential to be aware of this method's pitfalls, such as how biases can affect the results or the potential for low reliability. Keeping these in mind can help you review and assess research studies more accurately, giving you a better idea of whether the results can be trusted or have limitations.

Colorado State University. Experimental and quasi-experimental research .

American Psychological Association. Experimental psychology studies human and animals .

Mayrhofer R, Kuhbandner C, Lindner C. The practice of experimental psychology: An inevitably postmodern endeavor . Front Psychol . 2021;11:612805. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.612805

Mandler G. A History of Modern Experimental Psychology .

Stanford University. Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt . Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Britannica. Gustav Fechner .

Britannica. Hermann von Helmholtz .

Meyer A, Hackert B, Weger U. Franz Brentano and the beginning of experimental psychology: implications for the study of psychological phenomena today . Psychol Res . 2018;82:245-254. doi:10.1007/s00426-016-0825-7

Britannica. Georg Elias Müller .

McCambridge J, de Bruin M, Witton J. The effects of demand characteristics on research participant behaviours in non-laboratory settings: A systematic review . PLoS ONE . 2012;7(6):e39116. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039116

Laboratory experiments . In: The Sage Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. Allen M, ed. SAGE Publications, Inc. doi:10.4135/9781483381411.n287

Schweizer M, Braun B, Milstone A. Research methods in healthcare epidemiology and antimicrobial stewardship — quasi-experimental designs . Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol . 2016;37(10):1135-1140. doi:10.1017/ice.2016.117

Glass A, Kang M. Dividing attention in the classroom reduces exam performance . Educ Psychol . 2019;39(3):395-408. doi:10.1080/01443410.2018.1489046

Keskin M, Ooms K, Dogru AO, De Maeyer P. Exploring the cognitive load of expert and novice map users using EEG and eye tracking . ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf . 2020;9(7):429. doi:10.3390.ijgi9070429

Ho A, Hancock J, Miner A. Psychological, relational, and emotional effects of self-disclosure after conversations with a chatbot . J Commun . 2018;68(4):712-733. doi:10.1093/joc/jqy026

Haynes IV J, Frith E, Sng E, Loprinzi P. Experimental effects of acute exercise on episodic memory function: Considerations for the timing of exercise . Psychol Rep . 2018;122(5):1744-1754. doi:10.1177/0033294118786688

Torresin S, Pernigotto G, Cappelletti F, Gasparella A. Combined effects of environmental factors on human perception and objective performance: A review of experimental laboratory works . Indoor Air . 2018;28(4):525-538. doi:10.1111/ina.12457

Schumpe BM, Belanger JJ, Moyano M, Nisa CF. The role of sensation seeking in political violence: An extension of the significance quest theory . J Personal Social Psychol . 2020;118(4):743-761. doi:10.1037/pspp0000223

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Experimental Psychology: 10 Examples & Definition

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Experimental psychology refers to studying psychological phenomena using scientific methods. Originally, the primary scientific method involved manipulating one variable and observing systematic changes in another variable.

Today, psychologists utilize several types of scientific methodologies.

Experimental psychology examines a wide range of psychological phenomena, including: memory, sensation and perception, cognitive processes, motivation, emotion, developmental processes, in addition to the neurophysiological concomitants of each of these subjects.

Studies are conducted on both animal and human participants, and must comply with stringent requirements and controls regarding the ethical treatment of both.

Definition of Experimental Psychology

Experimental psychology is a branch of psychology that utilizes scientific methods to investigate the mind and behavior.

It involves the systematic and controlled study of human and animal behavior through observation and experimentation .

Experimental psychologists design and conduct experiments to understand cognitive processes, perception, learning, memory, emotion, and many other aspects of psychology. They often manipulate variables ( independent variables ) to see how this affects behavior or mental processes (dependent variables).

The findings from experimental psychology research are often used to better understand human behavior and can be applied in a range of contexts, such as education, health, business, and more.

Experimental Psychology Examples

1. The Puzzle Box Studies (Thorndike, 1898) Placing different cats in a box that can only be escaped by pulling a cord, and then taking detailed notes on how long it took for them to escape allowed Edward Thorndike to derive the Law of Effect: actions followed by positive consequences are more likely to occur again, and actions followed by negative consequences are less likely to occur again (Thorndike, 1898).

2. Reinforcement Schedules (Skinner, 1956) By placing rats in a Skinner Box and changing when and how often the rats are rewarded for pressing a lever, it is possible to identify how each schedule results in different behavior patterns (Skinner, 1956). This led to a wide range of theoretical ideas around how rewards and consequences can shape the behaviors of both animals and humans.

3. Observational Learning (Bandura, 1980) Some children watch a video of an adult punching and kicking a Bobo doll. Other children watch a video in which the adult plays nicely with the doll. By carefully observing the children’s behavior later when in a room with a Bobo doll, researchers can determine if television violence affects children’s behavior (Bandura, 1980).

4. The Fallibility of Memory (Loftus & Palmer, 1974) A group of participants watch the same video of two cars having an accident. Two weeks later, some are asked to estimate the rate of speed the cars were going when they “smashed” into each other. Some participants are asked to estimate the rate of speed the cars were going when they “bumped” into each other. Changing the phrasing of the question changes the memory of the eyewitness.

5. Intrinsic Motivation in the Classroom (Dweck, 1990) To investigate the role of autonomy on intrinsic motivation, half of the students are told they are “free to choose” which tasks to complete. The other half of the students are told they “must choose” some of the tasks. Researchers then carefully observe how long the students engage in the tasks and later ask them some questions about if they enjoyed doing the tasks or not.

6. Systematic Desensitization (Wolpe, 1958) A clinical psychologist carefully documents his treatment of a patient’s social phobia with progressive relaxation. At first, the patient is trained to monitor, tense, and relax various muscle groups while viewing photos of parties. Weeks later, they approach a stranger to ask for directions, initiate a conversation on a crowded bus, and attend a small social gathering. The therapist’s notes are transcribed into a scientific report and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

7. Study of Remembering (Bartlett, 1932) Bartlett’s work is a seminal study in the field of memory, where he used the concept of “schema” to describe an organized pattern of thought or behavior. He conducted a series of experiments using folk tales to show that memory recall is influenced by cultural schemas and personal experiences.

8. Study of Obedience (Milgram, 1963) This famous study explored the conflict between obedience to authority and personal conscience. Milgram found that a majority of participants were willing to administer what they believed were harmful electric shocks to a stranger when instructed by an authority figure, highlighting the power of authority and situational factors in driving behavior.

9. Pavlov’s Dog Study (Pavlov, 1927) Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, conducted a series of experiments that became a cornerstone in the field of experimental psychology. Pavlov noticed that dogs would salivate when they saw food. He then began to ring a bell each time he presented the food to the dogs. After a while, the dogs began to salivate merely at the sound of the bell. This experiment demonstrated the principle of “classical conditioning.”

10, Piaget’s Stages of Development (Piaget, 1958) Jean Piaget proposed a theory of cognitive development in children that consists of four distinct stages: the sensorimotor stage (birth to 2 years), where children learn about the world through their senses and motor activities, through to the the formal operational stage (12 years and beyond), where abstract reasoning and hypothetical thinking develop. Piaget’s theory is an example of experimental psychology as it was developed through systematic observation and experimentation on children’s problem-solving behaviors .

Types of Research Methodologies in Experimental Psychology

Researchers utilize several different types of research methodologies since the early days of Wundt (1832-1920).

1. The Experiment

The experiment involves the researcher manipulating the level of one variable, called the Independent Variable (IV), and then observing changes in another variable, called the Dependent Variable (DV).

The researcher is interested in determining if the IV causes changes in the DV. For example, does television violence make children more aggressive?

So, some children in the study, called research participants, will watch a show with TV violence, called the treatment group. Others will watch a show with no TV violence, called the control group.

So, there are two levels of the IV: violence and no violence. Next, children will be observed to see if they act more aggressively. This is the DV.

If TV violence makes children more aggressive, then the children that watched the violent show will me more aggressive than the children that watched the non-violent show.

A key requirement of the experiment is random assignment . Each research participant is assigned to one of the two groups in a way that makes it a completely random process. This means that each group will have a mix of children: different personality types, diverse family backgrounds, and range of intelligence levels.

2. The Longitudinal Study

A longitudinal study involves selecting a sample of participants and then following them for years, or decades, periodically collecting data on the variables of interest.

For example, a researcher might be interested in determining if parenting style affects academic performance of children. Parenting style is called the predictor variable , and academic performance is called the outcome variable .

Researchers will begin by randomly selecting a group of children to be in the study. Then, they will identify the type of parenting practices used when the children are 4 and 5 years old.

A few years later, perhaps when the children are 8 and 9, the researchers will collect data on their grades. This process can be repeated over the next 10 years, including through college.

If parenting style has an effect on academic performance, then the researchers will see a connection between the predictor variable and outcome variable.

Children raised with parenting style X will have higher grades than children raised with parenting style Y.

3. The Case Study

The case study is an in-depth study of one individual. This is a research methodology often used early in the examination of a psychological phenomenon or therapeutic treatment.

For example, in the early days of treating phobias, a clinical psychologist may try teaching one of their patients how to relax every time they see the object that creates so much fear and anxiety, such as a large spider.

The therapist would take very detailed notes on how the teaching process was implemented and the reactions of the patient. When the treatment had been completed, those notes would be written in a scientific form and submitted for publication in a scientific journal for other therapists to learn from.

There are several other types of methodologies available which vary different aspects of the three described above. The researcher will select a methodology that is most appropriate to the phenomenon they want to examine.

They also must take into account various practical considerations such as how much time and resources are needed to complete the study. Conducting research always costs money.

People and equipment are needed to carry-out every study, so researchers often try to obtain funding from their university or a government agency.

Origins and Key Developments in Experimental Psychology

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (1832-1920) is considered one of the fathers of modern psychology. He was a physiologist and philosopher and helped establish psychology as a distinct discipline (Khaleefa, 1999).

In 1879 he established the world’s first psychology research lab at the University of Leipzig. This is considered a key milestone for establishing psychology as a scientific discipline. In addition to being the first person to use the term “psychologist,” to describe himself, he also founded the discipline’s first scientific journal Philosphische Studien in 1883.

Another notable figure in the development of experimental psychology is Ernest Weber . Trained as a physician, Weber studied sensation and perception and created the first quantitative law in psychology.

The equation denotes how judgments of sensory differences are relative to previous levels of sensation, referred to as the just-noticeable difference (jnd). This is known today as Weber’s Law (Hergenhahn, 2009).

Gustav Fechner , one of Weber’s students, published the first book on experimental psychology in 1860, titled Elemente der Psychophysik. His worked centered on the measurement of psychophysical facets of sensation and perception, with many of his methods still in use today.

The first American textbook on experimental psychology was Elements of Physiological Psychology, published in 1887 by George Trumball Ladd .

Ladd also established a psychology lab at Yale University, while Stanley Hall and Charles Sanders continued Wundt’s work at a lab at Johns Hopkins University.

In the late 1800s, Charles Pierce’s contribution to experimental psychology is especially noteworthy because he invented the concept of random assignment (Stigler, 1992; Dehue, 1997).

Go Deeper: 15 Random Assignment Examples

This procedure ensures that each participant has an equal chance of being placed in any of the experimental groups (e.g., treatment or control group). This eliminates the influence of confounding factors related to inherent characteristics of the participants.

Random assignment is a fundamental criterion for a study to be considered a valid experiment.

From there, experimental psychology flourished in the 20th century as a science and transformed into an approach utilized in cognitive psychology, developmental psychology, and social psychology .

Today, the term experimental psychology refers to the study of a wide range of phenomena and involves methodologies not limited to the manipulation of variables.

The Scientific Process and Experimental Psychology

The one thing that makes psychology a science and distinguishes it from its roots in philosophy is the reliance upon the scientific process to answer questions. This makes psychology a science was the main goal of its earliest founders such as Wilhelm Wundt.

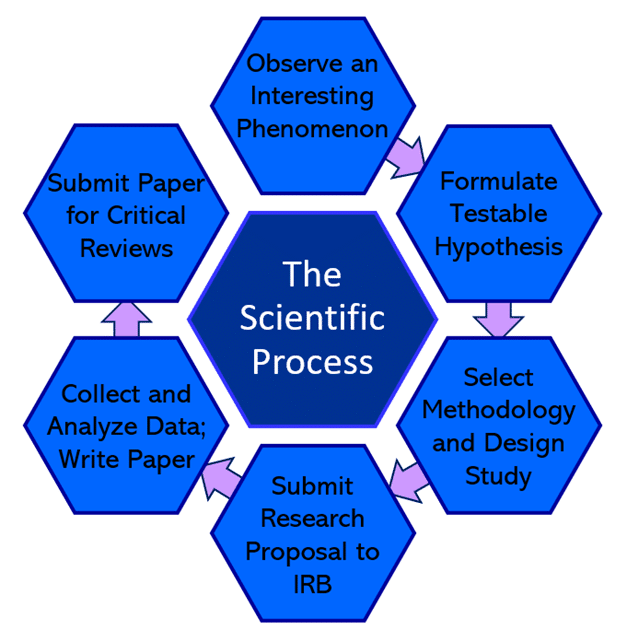

There are numerous steps in the scientific process, outlined in the graphic below.

1. Observation

First, the scientist observes an interesting phenomenon that sparks a question. For example, are the memories of eyewitnesses really reliable, or are they subject to bias or unintentional manipulation?

2. Hypothesize

Next, this question is converted into a testable hypothesis. For instance: the words used to question a witness can influence what they think they remember.

3. Devise a Study

Then the researcher(s) select a methodology that will allow them to test that hypothesis. In this case, the researchers choose the experiment, which will involve randomly assigning some participants to different conditions.

In one condition, participants are asked a question that implies a certain memory (treatment group), while other participants are asked a question which is phrased neutrally and does not imply a certain memory (control group).

The researchers then write a proposal that describes in detail the procedures they want to use, how participants will be selected, and the safeguards they will employ to ensure the rights of the participants.

That proposal is submitted to an Institutional Review Board (IRB). The IRB is comprised of a panel of researchers, community representatives, and other professionals that are responsible for reviewing all studies involving human participants.

4. Conduct the Study

If the IRB accepts the proposal, then the researchers may begin collecting data. After the data has been collected, it is analyzed using a software program such as SPSS.

Those analyses will either support or reject the hypothesis. That is, either the participants’ memories were affected by the wording of the question, or not.

5. Publish the study

Finally, the researchers write a paper detailing their procedures and results of the statistical analyses. That paper is then submitted to a scientific journal.

The lead editor of that journal will then send copies of the paper to 3-5 experts in that subject. Each of those experts will read the paper and basically try to find as many things wrong with it as possible. Because they are experts, they are very good at this task.

After reading those critiques, most likely, the editor will send the paper back to the researchers and require that they respond to the criticisms, collect more data, or reject the paper outright.

In some cases, the study was so well-done that the criticisms were minimal and the editor accepts the paper. It then gets published in the scientific journal several months later.

That entire process can easily take 2 years, usually more. But, the findings of that study went through a very rigorous process. This means that we can have substantial confidence that the conclusions of the study are valid.

Experimental psychology refers to utilizing a scientific process to investigate psychological phenomenon.

There are a variety of methods employed today. They are used to study a wide range of subjects, including memory, cognitive processes, emotions and the neurophysiological basis of each.

The history of psychology as a science began in the 1800s primarily in Germany. As interest grew, the field expanded to the United States where several influential research labs were established.

As more methodologies were developed, the field of psychology as a science evolved into a prolific scientific discipline that has provided invaluable insights into human behavior.

Bartlett, F. C., & Bartlett, F. C. (1995). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology . Cambridge university press.

Dehue, T. (1997). Deception, efficiency, and random groups: Psychology and the gradual origination of the random group design. Isis , 88 (4), 653-673.

Ebbinghaus, H. (2013). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Annals of neurosciences , 20 (4), 155.

Hergenhahn, B. R. (2009). An introduction to the history of psychology. Belmont. CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning .

Khaleefa, O. (1999). Who is the founder of psychophysics and experimental psychology? American Journal of Islam and Society , 16 (2), 1-26.

Loftus, E. F., & Palmer, J. C. (1974). Reconstruction of auto-mobile destruction : An example of the interaction between language and memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal behavior , 13, 585-589.

Pavlov, I.P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes . Dover, New York.

Piaget, J. (1959). The language and thought of the child (Vol. 5). Psychology Press.

Piaget, J., Fraisse, P., & Reuchlin, M. (2014). Experimental psychology its scope and method: Volume I (Psychology Revivals): History and method . Psychology Press.

Skinner, B. F. (1956). A case history in scientlfic method. American Psychologist, 11 , 221-233

Stigler, S. M. (1992). A historical view of statistical concepts in psychology and educational research. American Journal of Education , 101 (1), 60-70.

Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. Psychological Review Monograph Supplement 2 .

Wolpe, J. (1958). Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Appendix: Images reproduced as Text

Definition: Experimental psychology is a branch of psychology that focuses on conducting systematic and controlled experiments to study human behavior and cognition.

Overview: Experimental psychology aims to gather empirical evidence and explore cause-and-effect relationships between variables. Experimental psychologists utilize various research methods, including laboratory experiments, surveys, and observations, to investigate topics such as perception, memory, learning, motivation, and social behavior .

Example: The Pavlov’s Dog experimental psychology experiment used scientific methods to develop a theory about how learning and association occur in animals. The same concepts were subsequently used in the study of humans, wherein psychology-based ideas about learning were developed. Pavlov’s use of the empirical evidence was foundational to the study’s success.

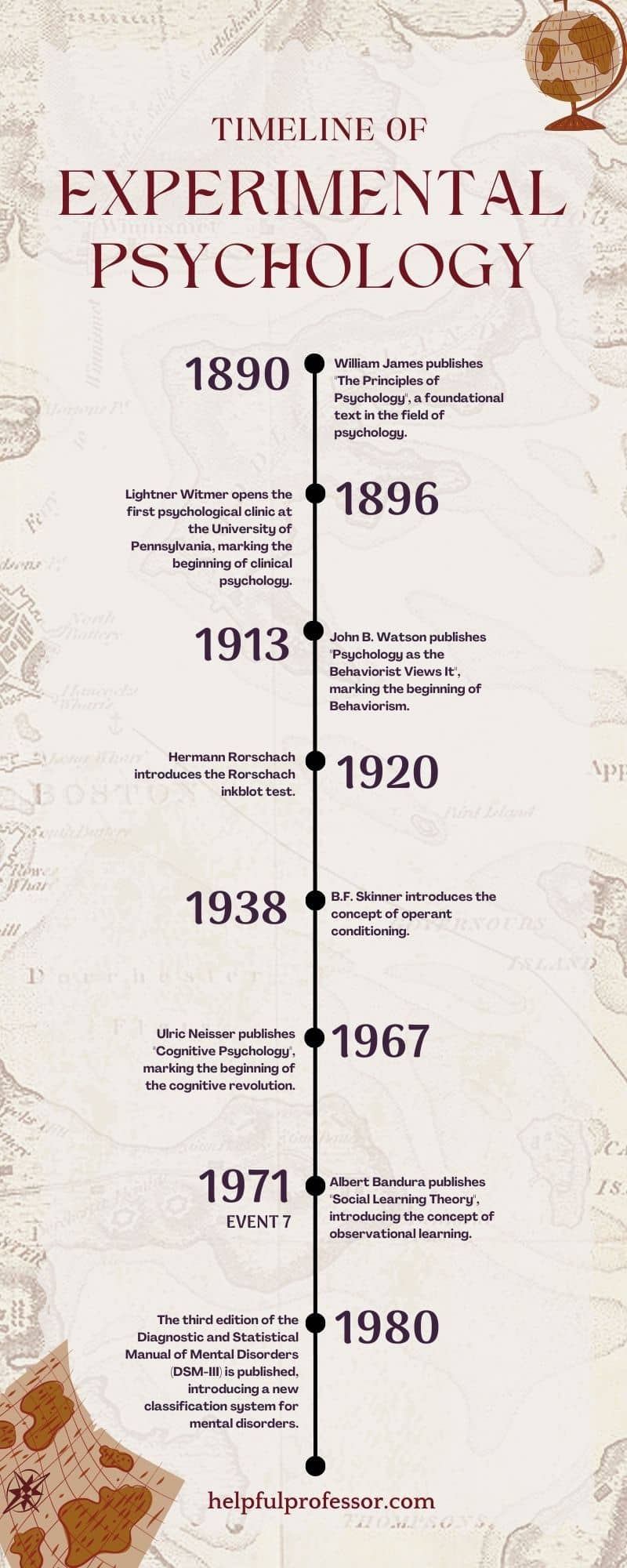

Experimental Psychology Milestones:

1890: William James publishes “The Principles of Psychology”, a foundational text in the field of psychology.

1896: Lightner Witmer opens the first psychological clinic at the University of Pennsylvania, marking the beginning of clinical psychology.

1913: John B. Watson publishes “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It”, marking the beginning of Behaviorism.

1920: Hermann Rorschach introduces the Rorschach inkblot test.

1938: B.F. Skinner introduces the concept of operant conditioning .

1967: Ulric Neisser publishes “Cognitive Psychology” , marking the beginning of the cognitive revolution.

1980: The third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) is published, introducing a new classification system for mental disorders.

The Scientific Process

- Observe an interesting phenomenon

- Formulate testable hypothesis

- Select methodology and design study

- Submit research proposal to IRB

- Collect and analyzed data; write paper

- Submit paper for critical reviews

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Experimental Studies

- Reference work entry

- Cite this reference work entry

- Sandra Šipetić Grujičić 2

1238 Accesses

7 Altmetric

Intervention studies

Experimental study is “study in which conditions are under the direct control of the investigator” (Last 2001 ). It is employed to test the efficacy of a preventive or therapeutic measure.

Experimental studies can provide the strongest evidence about the existence of a cause-effect relationship .

Basic Characteristics

Types of experimental studies.

There are two different types of experimental studies: therapeutic and prevention studies (Webb et al. 2005 ).

In therapeutic studies ( clinical trials ), different medicines or medical procedures for a given disease are compared in a clinical setting.

Trials that are conducted on healthy or apparently healthy individuals with the aim of preventing future morbidity or mortality are called preventive studies . Preventive studies include community study , in which the intervention is applied to groups, and field study , in which the intervention is applied to healthy individuals at usual or high risk of...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bhopal R (2002) Concepts of epidemiology. An integrated introduction to the ideas, theories, principles, and methods of epidemiology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Google Scholar

Dawson B, Trapp R (2001) Basic and clinical biostatistics, 3rd edn. Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill, New York

Fraceschi S, Plummer M (2005) Intervention trials. In: Ahrens W, Pigeot I (eds) Handbook of epidemiology. Springer, Berlin, pp 345–370

Friedman LM, Schron EB (2002) Methodology of intervention trials in individuals. In: Detels R, McEwen J, Beaglehole R, Tanaka H (eds) Oxford Textbook of Public Health, 4th edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 569–581

Gordis L (2004) Epidemiology, 3rd edn. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia

Last J (2001) A dictionary of epidemiology, 4th edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Webb P, Bain C, Pirozzo S (2005) Essential epidemiology: an introduction for students and health professionals. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Epidemiology, School of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia

Sandra Šipetić Grujičić

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Network EUROlifestyle Research Association Public Health Saxony-Saxony Anhalt e.V. Medical Faculty, University of Technology, Fiedlerstr. 27, 01307, Dresden, Germany

Wilhelm Kirch ( Professor Dr. Dr. ) ( Professor Dr. Dr. )

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2008 Springer-Verlag

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Šipetić Grujičić, S. (2008). Experimental Studies . In: Kirch, W. (eds) Encyclopedia of Public Health. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5614-7_1092

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5614-7_1092

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-1-4020-5613-0

Online ISBN : 978-1-4020-5614-7

eBook Packages : Medicine Reference Module Medicine

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Experimental Psychology: History, Method and Characteristics

The Experimental psychology Is a stream that studies the psychological phenomena using an experimental methodology based on observation.

It guarantees a scientific practice and involves the observation, manipulation and registration of the variables that affect a subject under study.

Experimental psychologists are interested in studying human behavior by manipulating variables in controllable situations and in unnatural environments that affect and influence behavior.

Gustav Theodor Fechner Was one of the pioneers in the use of the experimental when trying to prove the relation between physical and sensorial magnitudes, in 1860.

However, it was in 1879 when Wilhelm Wundt , Considered one of the founders of this current, created the first laboratory of experimental psychology.

Definition of experimental psychology

This current of psychology defends the experimental method as the most suitable form for the study of human behavior.

Experimental psychology considers that psychological phenomena can be analyzed by experimental methods consisting in the observation, manipulation and recording of dependent, independent and extraneous variables that influence the object of study.

Many psychologists have used this method when carrying out their work to address multiple issues such as memory , Learning, sensation, perception, motivation and development processes, among others.

Professionals who adopt this method want to know the behavior of a subject by manipulating variables in controlled environments. The contexts in which they are carried out are the laboratories and instruments are used that guarantee a control and an exhaustive precision in their investigations.

The experiments can be performed in humans but mostly animals are used, because many times for ethical reasons people can not be used to perform such tests. In addition, animals provide greater availability and control to researchers.

The most scientific part of psychology is unified with experimental psychology, because the use of its methodology guarantees a scientific practice through observation and experimentation, removing the laws of behavior and mental processes.

With its emergence in the nineteenth century, psychology begins to focus and become interested in the study of observable phenomena, thus giving rise to an empirical science, that is, based on observation and experience of events.

Later, experimental psychology would use rigorous methods and instruments to carry out the measurements in its investigations.

Experimental psychology emerges in Germany as a modern discipline with Wundt, who created the first experimental laboratory in 1879 and introduced a mathematical and experimental approach to research.

Earlier in 1860 Gustav Theodor Fechner, a German psychologist, attempted to test and reason the link between physical and sensory magnitudes through experimental data in his work Elements of psychophysics .

Other authors who contributed to this growing science were Charles Bell , A British physiologist who investigated nerves; Ernst Heinrich Weber , A German physician and considered one of its founders and Oswald Külpe , The principal founder of the Würzburg School in Germany, among others.

The appearance of different schools was due to this tendency to the experimentation of the time, whose purpose was to try to observe the degree of relationship between the biological and the psychological.

Among these schools is the Russian who was interested in neurophysiology and was initiated by Pavlov Y Bechterev . Functionalism, which seeks to demonstrate the biological laws that delimit the behavior and behaviorism of Watson .

In the twentieth century behaviorism was the predominant school within psychology in general and especially in the United States. It is the branch of psychology that set aside mental phenomena within experimental psychology.

In Europe, however, this was not the case, since psychology was influenced by such authors as Craik, Hick and Broadbent who focused on subjects such as attention, thought and memory, thus laying the foundations of cognitive psychology.

In the last half of the century, psychologists used multiple methods, not only focused and limited to a strictly experimental approach.

In addition, the experimental method is used in many different fields within psychology such as social psychology and developmental psychology.

Experimental method

Experimental psychology considers that psychological phenomena can be studied through this method, thus constituting one of the bases of psychology as a science.

It involves the observation, manipulation and recording of dependent, independent and extraneous variables that are the object of study, in order to be able to describe and explain them in terms of their relation to human behavior.

This method aims to identify the causes and evaluate the consequences, the researcher tries to find a causality between different variables.

On the one hand, there is the medium variable that would act as an independent variable. The dependent would be that which is related to the behavior of the subject. Finally, all external factors influencing this would be weird variables.

The experiment is carried out in a controlled environment such as a laboratory, where the experimenter can manipulate variables and control those that can affect the others. In addition, it can thus form specific experimental groups of subjects according to their study interests.

The researcher is the one who creates the necessary conditions to be able to carry out the study and to apply the independent variable when he sees fit. In addition to this method can be repeated conditions to check the results as well as alter them to see the differences of behavior to study between different situations.

In this approach, the experimenter manipulates circumstances to control their increase or decrease as well as their effect on the observed behaviors, to be able to describe why that situation or change occurs.

Many times before carrying out an investigation one resorts to pilot experiments that are tests of the experiment to study some aspects of him. In addition the experiments have another positive part because being carried out in these controlled contexts can be replicated by other researchers in future situations.

Characteristics of experimental research

Some of the characteristics of experimental research are as follows:

- Subjects are randomly arranged into equivalent groups, giving rise to statistical equivalence so that the differences between the results are not due to initial differences between groups of subjects.

- Existence of two or more groups or conditions to be able to carry out the comparison between them. Experiments can not be performed with a single group or condition to be compared.

- Management of an independent variable, in the form of different values or circumstances. This direct manipulation is done to be able to observe the changes that it produces in the dependent variables. In addition, the assignment of values and conditions must be done by the researcher, because if this were not so, it would not be considered a real experiment.

- Measure each dependent variable by assigning numerical values so that the result can be evaluated and thus speak of an experimental investigation.

- Have a design with which you can control to a greater extent the influence of the foreign variables and to avoid that the results are affected by them.

- Use inferential statistics to make generalizations of research to the population.

Phases of an experiment

1- approaching a knowledge problem.

Choosing the problem to be investigated depends on the experimenter and what you want to study, the research questions have to be able to be solved through an experimental process.

Depending on the problem, the methodological approach to be followed will be delimited.

2- Hypothesis Formulation

The hypotheses are statements that are formulated and that anticipate the results that could be obtained from the research, relate at least two variables and must be described in empirical terms, being able to be observed and measurable.

3- Making an appropriate design

With the design, the procedure or work plan of the researcher is plotted, indicating what is going to be done and how the study will be carried out, from the variables involved to the assignment of the subjects to the groups.

4- Collection and analysis of data

For the collection of data there are multiple instruments that are valid and reliable, and techniques that will be better or worse adapted and that will present advantages and disadvantages.

The analysis of the data is carried out by organizing the information so that it can be described, analyzed and explained.

5- Conclusions

In the conclusions, it is developed the fulfillment or not of the hypotheses raised, the limitations of the research work, the methodology that has been followed, implications for the practice, generalization at the population level, as well as future lines of research.

Objective and conditions of the experimental method

Its objective is to investigate the causal relationships between variables, that is, to analyze the changes that occurred in the dependent variable (behavior) as a consequence of the different values presented by the independent variable (external factor).

The conditions to be able to conclude that there is a relationship between variables are: