- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- The Lit Hub Podcast

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- I’m a Writer But

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Behind the Mic

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- Emergence Magazine

- The History of Literature

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

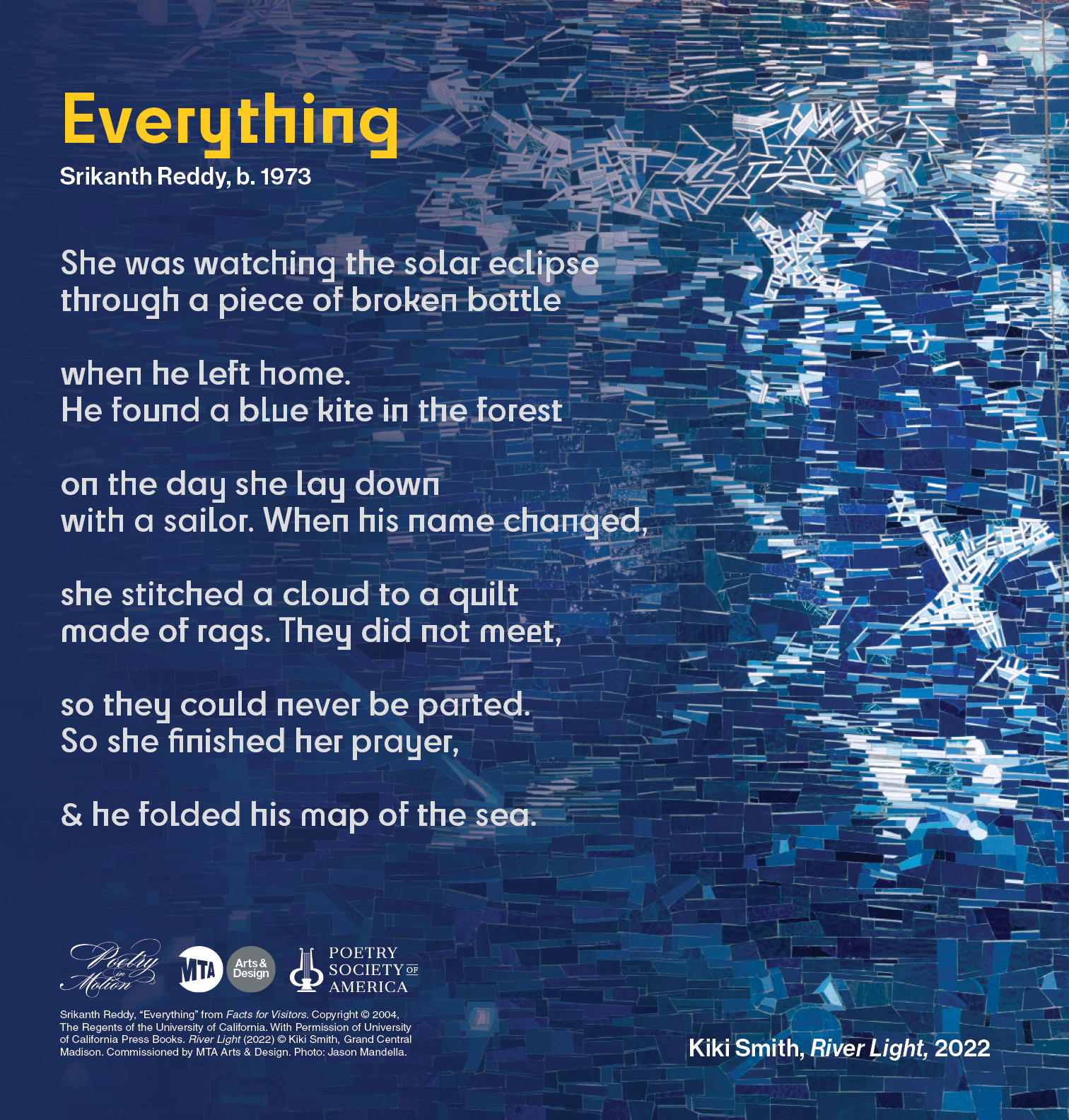

Celebrating 25 Years of Poetry in Motion

Writing back to a legacy, 200 plus poems strong (and counting).

When I enter a New York City subway car, I first scout for an empty seat. But almost simultaneously, I look for Poetry in Motion posters. Riding the rails with the likes of former Poet Laureate Billy Collins or current Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith is only part of the fun—I also love to speculate about the associations the poems might summon for other straphangers, who number nearly six million every day.

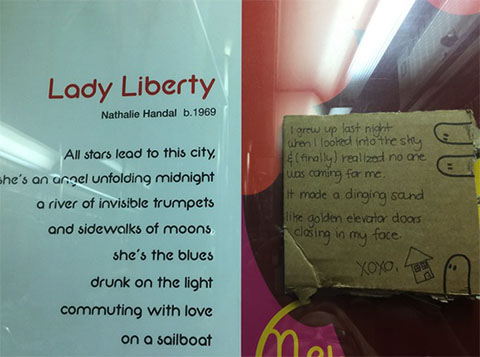

Last December, I was delighted to look down the aisle on a not-too-crowded 6 train and spot a piece of cardboard taped to Nathalie Handal’s “Lady Liberty.” On it was a handwritten poem—no title, no name. But following “XOXO,” there was a signature of sorts: three finger people with dots for eyes beside a simply-drawn house. A love poem back to Poetry in Motion, I quickly and arbitrarily concluded.

Poetry in Motion was founded in 1992 as a joint effort between the Poetry Society of America and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Inspired by a similar program in the London tube, it aims to ignite a broad range of conversations in public transportation. Since its New York debut, Poetry in Motion has appeared in more than 25 other cities across the nation. A new anthology edited by Alice Quinn, The Best of Poetry in Motion , will include half of the 200-plus poems featured on subways and buses, as well as a history of the collaboration.

Molly Peacock, the president of the PSA at the time of Poetry in Motion’s creation, described the program’s goals in the introduction to an earlier anthology:

Since nationalities representing the entire world ride on New York City’s public transit, we try to reflect that world. We look for poems that will speak to all ethnicities, genders, ages. We look for voices that will stimulate the exhausted, inspire the frustrated, comfort the burdened, and enchant even the youngest passengers.

Following its reboot in 2012 under the leadership of Sandra Bloodworth, the program pairs art commissioned by MTA Arts & Design with poetry; each quarter, two poems are displayed throughout the transit system. According to MTA estimates of subway ridership, these reach 1.7 billion potential readers annually. Poems can also be found on roughly five percent of MetroCards, putting millions of poems in riders’ pockets every year. As New York Times columnist Jim Dwyer noted , the MTA “could claim to be the most successful publisher of poetry in history.”

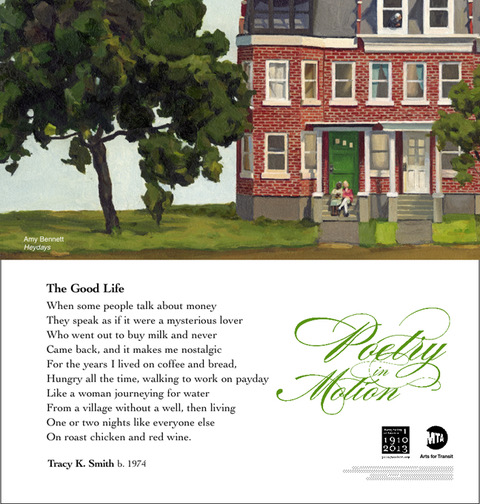

Tracy K. Smith treasured the NYC posters as a MFA grad student at Columbia University as “morsels of ecstatic language to think about and carry with me.” Years later, her poem “The Good Life” was featured in 2013 and is reportedly one of the program’s most popular.

“Having my own poem on display in the trains was an enormous affirmation,” said Smith, who had won the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry the year before. “Even more emphatic was the feeling of community I got whenever I’d receive word from a fellow New Yorker who had glimpsed ‘The Good Life’ on their commute. Your poem touched me. Or , I remember those days of living paycheck to paycheck that your poem describes. Or , I’ve never really read poetry before, but I memorized your poem on my way to work today.”

A year later, “Heaven” by Patrick Phillips received a similarly enthusiastic response—some admirers even looked him up and reached out. A father wanted permission to make t-shirts of the poem for the third anniversary of his son’s suicide. Adults told him how deeply they missed their parents. Several composers wanted permission to set it to music. One woman carried a MetroCard with the poem on the back for a year, then retired it to her bulletin board at work once the card expired.

One reader, whose mother had recently died, thanked Phillips for the comfort that his poem provided. After he replied with condolences, she emailed again with this question: I was wondering if I might ask you the inspiration for that poem. If it’s too personal, I understand.

Phillips explained that the poem was inspired by his grief at the fact that his young sons won’t remember his wife’s father, who died “too young, from really merciless prostate cancer , ” and by his envy of Renaissance poets George Herbert and Ben Jonson’s faith in a heavenly reunion. Moved, he ended his reply, “And now I’m all teary on my commute home!”

Others expressed their appreciation for a moment of reflection on their way back from work. “Thank you for creating this masterpiece that I enjoy ever so often when I get on THAT car on THAT Queens-bound A train on my way home after a long hard day of living in New York City , ” one such reader wrote Phillips.

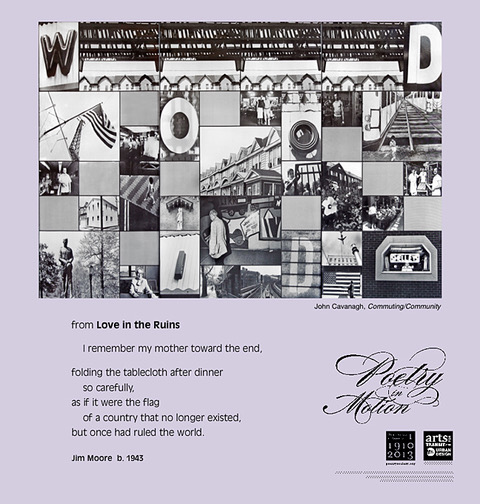

Jim Moore, who lives in Minneapolis, was surprised by how many friends and strangers emailed him about his contribution to the project, “Love in the Ruins.” During a visit to New York, his wife introduced him to an old acquaintance as a poet. Without realizing the connection, the friend relayed how she burst into tears reading a subway poem about a mother folding a tablecloth—his poem. “It was an amazing moment,” Moore said.

Since 2013, Moore’s had an ongoing email relationship with a woman from Connecticut who he has never met. She told him that she tucked the poem into her calendar holder as a reminder of her deceased mother and how made dinners as special as holiday feasts every night. “Yesterday was one of those times,” she emailed Moore in July. “I sat down, read it, teared up… The memory of the subway, my finding you, and your incredibly generous response remains so lovely in my mind.”

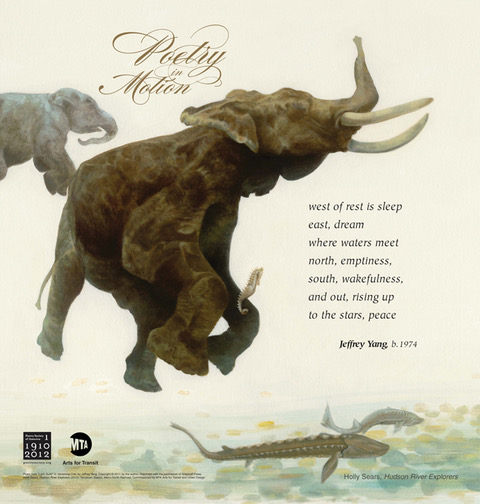

Jeffrey Yang, whose untitled poem from the sequence “Lyric Suite” was featured in 2012, was also amazed by the range of reactions to his work. “One film director has used it in his new movie, a musician has set it to music, many friends have described spur of the moment discussions with other train riders about it, a philosopher started a long online group discussion focused on it, a literary critic used it as an epigraph in her new book, a nun wrote me a glowing note about it, random people still post stills of it on the internet,” he told me. “The list goes on and on and is weirdly astonishing.”

Former Poet Laureate Billy Collins has the distinction of two poem commissions by the MTA: “Grand Central” for the station’s 100 th anniversary and “Subway” for the launch of the 2nd Ave Subway. Collins read “Subway” on the Dec. 31, 2016 inaugural ride, which I attended.

“That poet guy must have walked the tracks before. Or he has a good imagination,” said a lanky electrician holding a postcard of the poem as we both exited the station that night. This comment was more than enough to thrill Collins. “The poem intends to draw grateful attention to those very workers,” he explained after I passed the message along.

My favorite pairing of visual art and poem is “Primavera,” a mosaic by Raúl Colón at the top of a stairway at the 191st Street 1 Train stop. That was my exit when I coached eighth graders at The Equity Project with their application essays for high school. As a warmup, I’d suggest they substitute as many nouns as they wanted in “Ragtime” by Kevin Young to say something unique about themselves, which sometimes extracted compelling details for their essays.

Other teachers have told PSA how they’ve used the Poetry in Motion poems in their classroom. A minister asked for permission (not that he needed it) to use one of the poems in his sermon. A nun wanted copies of another for senior citizens. Parents have described how they talk about the poems with their children.

“It’s a big part of how Ruby (age 6) learned to read: we practice on those poems,” one parent told. “We purposefully look for a subway car with [Poetry in Motion] posters in it, and we talk about them in the morning,” another wrote to PSA. “It brings my son and I closer together.”

Although my conclusion about the cardboard taped to “Lady Liberty”—that it’s a love letter to Poetry in Motion—is just conjecture, it’s not an unfounded assumption. The project has impacted countless people, writers and passengers alike. Whoever the unnamed poet is, they’re undeniably talking back to a legacy, 200 plus poems strong and counting.

__________________________________

Many of the poets featured in the new anthology will read their contributions and relay their stories on October 25 at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center at Lincoln Center. Poets include Billy Collins, Aracelis Girmay, Major Jackson, Ada Limón, Jim Moore, Paul Muldoon, Marilyn Nelson, Patrick Phillips, Katha Pollitt, and Kevin Young. Admission is free but reservations required through Eventbrite .

The Poetry in Motion atlas on the poetrysociety.org website offers a sampling of poems from 25 cities, searchable by city and poem title. Poet and artists bios available here .

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Catherine Woodard

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

We Have Always Dreamed of Other Worlds

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Poetry & Poets

Explore the beauty of poetry – discover the poet within

What Does Poetry In Motion Mean

Definition of Poetry in Motion

The term “poetry in motion” is typically used to describe something graceful, effortless and beautiful. It can refer to a ballet performance, a piece of art or a piece of writing that has strong emotion, creativity, and a powerful impact. The phrase is said to come from an old saying that is attributed to Alexander Pope in the 1700s. He wrote that “true elegance is all of ease, so graceful and so free, like some sweet poem in a dream, that’s poetry in motion”. In simpler terms, this means that when you are doing something that has that “it factor”, then you are in a state of being where everything is easy, carefree and almost like a dream – you are in a state of poetry in motion.

The Power of Poetry in Motion

When something is described as poetry in motion, it doesn’t just mean that it is graceful in a physical sense. It can also refer to a powerful emotional expression. A great example of this is the way a poet can use language to paint inspiring pictures with words. They can bring about powerful emotions through their choice of words and their ability to convey a message. Likewise, a musician can create an emotional soundscape that can transport the listener to a realm of feeling through their skilled playing and composition. Just as Alexander Pope wrote that painting a “sweet poem in a dream” can be poetry in motion, so too can the senses be moved through music or art.

The Role of Expertise

When something is said to be poetry in motion, it is usually referring to something that has been created with skill and expertise. A ballet performance, a painting or a piece of music might seem effortless, but they are usually the result of years of dedication, practice and hard work. It’s these things that allow the performer or artist to be in a state of poetry in motion, where their performance is so fluid and graceful that it can seem almost effortless to the audience.

What Makes Something Poetry in Motion?

At its core, the phrase “poetry in motion” is about the impact that something has on the observer. It’s about the feeling that something gives off, the way that it transports the listener or viewer to another place. Whether it is a painting, a ballet performance or even a poem, the power lies in the emotions and feelings that it evokes. And it is that power that makes it poetry in motion.

The Impact of Poetry in Motion

Poetry in motion is not just about the physical elegance of a thing. It has the power to affect and inspire those that experience it. A great example of this is the way the world fell in love with a young girl called Misty Copeland who became the first African American female soloist in the American Ballet Theater in 2015. The power of her performance, combined with her story of determination and her courage, propelled her to global fame overnight and showed the world the beauty of poetry in motion.

Applying Poetry in Motion in Everyday Life

The concept of poetry in motion is not just restricting to the fields of art and music. We can all strive to bring a sense of grace, elegance and beauty to our day-to-day lives. This could be as simple as learning to write with a calligraphic pen, engaging in activities like yoga that require poise and practice, or simply finding ways to access inner-peace and enjoy the present moment. In a way, cultivating these habits can allow us to bring a sense of poetry into our everyday lives.

The Place of Poetry in Modern Culture

The concept of poetry in motion has been embraced by many artists, musicians and dancers throughout history. In more recent times, poets like Rupi Kaur, Billy Collins and Nayyirah Waheed have gained global recognition for the power of their writing and its ability to evoke emotion and inspire. Similarly, modern-day dancers have become superstars thanks to their graceful and powerful performances. Together, this shift in the perception of poetry from something stuffy to something modern and powerful has helped once again show the world the power of poetry in motion.

The Significance of Poetry in Motion

Ultimately, when something is described as poetry in motion, it’s a recognition of the beauty that comes when skill, artistry and passion come together. It’s a reminder that even in our everyday lives, we can strive to achieve a state of ease and grace, no matter how small or insignificant the task might seem. When we strive to encapsulate that sensation, we are truly in a state of “poetry in motion”.

The Art of Crafting Poetry in Motion

The beauty of poetry in motion is that it can come in any form and evoke an emotional reaction. To craft something that can convey this feeling, it is important to have an eye for detail, an understanding of beauty and a passion for the craft. Poets, dancers, musicians, and other artists combine practice and skill with their knowledge of the craft and their hard work to create something that exudes grace and elegance.

The Benefits of Experiencing Poetry in Motion

Experiencing poetry in motion can be deeply fulfilling and inspiring. It can motivate us to strive for perfection in our work, to strive for excellence and to see beauty and grace in the things that we do. It can also help us to relax, enjoy the moment and simply take in the beauty of a thing, regardless of how small or insignificant it might seem.

The Emotional Power of Poetry in Motion

The emotional power of poetry in motion can’t be underestimated. Be it a poem, a dance, or a piece of music, when it is done with skill and feeling, it can evoke powerful emotions in the listener. It can move them to tears, inspire them to action and give them hope in the face of adversity. That is the true power of poetry in motion.

Modern Expression of Poetry in Motion

In modern society, forms of expression such as rap, hip-hop and spoken word are becoming more popular. Through the combination of rhythmic beats and witty rhymes, these genres of expression can evoke powerful emotion in the listener, just like a poem can. Even though these art forms may seem far removed from traditional forms of poetry, they still embody many of the same themes and techniques that are used in traditional forms of poetry. This, combined with their modern beats, makes them a form of poetry in motion.

The Meaning Behind Poetry in Motion

At the end of the day, what sets poetry in motion apart from other forms of artistic expression is its ability to move the listener or viewer emotionally. It is this emotional connection that makes poetry in motion so powerful, regardless of whether it is a traditional form or a more modern style. As Mark Twain once said, “the difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter”. This holds true for poetry in motion, as the difference between a powerful performance and one that lacks feeling is enormous.

Bringing Poetry to Life

Poetry in motion is all about bringing something to life. Whether it’s a poem, a piece of music or a painting, the aim is to create something that can move the senses, that can inspire and that can bring people together. This can be achieved through skilled writing, playing, painting, or any other form of artistic expression. When those skills come together with the power of emotion, then something truly special can be created – something that is truly poetry in motion.

Minnie Walters

Minnie Walters is a passionate writer and lover of poetry. She has a deep knowledge and appreciation for the work of famous poets such as William Wordsworth, Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, and many more. She hopes you will also fall in love with poetry!

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- Poems & Essays

- Poetry in Motion NYC

Poetry In Motion > Everything

Poetry in Motion

- Archive tours

- Poetry Channel

- Festival 2024

- Festival archive 1970-2023

- C. Buddingh'-Prize

- Poet in Residence

- Het gedicht is een bericht

- For schools

- For organisations and companies

- Workshops in leisure time

- In session Now

- Spraakzaam Rotterdam

- Work at Poetry

- Foundation board & Governance

- Poets & Poems

Poetry in Motion

_w336.jpg)

Lü: What is poetry? That's always a big question. As far as I'm concerned, poetry means that form of writing most capable of providing a motion internal to language, but in the broadest sense of form, it is becoming more and more difficult for us to define what poetry is. In my view, poetry is precisely that poetic kind of writing that is impossible to define but which gestures towards a certain possibility.

Zeng: What phases have you passed through in your writing? What have been the main characteristics and pursuits of these various phases?

Lü: Generally speaking, the years from 1979 to 1981 can be thought of as the years when I was just beginning to learn. Back then, I was studying commercial art at the Xiamen Arts and Crafts College, and the poem that most exemplifies that period is 'Women and the Nights of Wojiao'. Following that, from the end of the 1980s to the early 1990s, was another period. Let's say that in that phase I became relatively more self-conscious as a writer. By this time, I was doing advertising work for a book-store, and a string of my poems were being published, as well as my first poetry collections. The decade after that could be called my third phase. In that period, I spent one half of my time living in New York and the other in my home province of Fujian. Perhaps you could say that my creative work had reached the stage that Confucius called "standing firm". By that I mean that although, superficially, my individual style was becoming more and more mature, at the same time this implied a "lack of doubt". The features of the poetry of my earliest phase were like those of the many people who were eager to learn about poetry in those days—I was quite influenced by the experimental writing techniques of menglong or 'obscure' poetry. On the one hand, I worked hard to find novel subjects for my poetry, as well as lines of great compression and contrasts between bizarre images; I also strove to express a certain feeling of the modern. On the other hand, in terms of aesthetic taste, I was still extremely traditional—I myself think that this was a carrying of the legacy of traditional poetry as far as I understood it. In addition, pure poetry was another goal of my early writing. Actually, this was only really a matter of trying to create something new and original, trying out different ways of writing, most of it rather imitative. Ironically, the poem 'Women and the Nights of Wojiao' I mentioned before seemed to unfold in a relaxed, prose-like manner, and deviated from my views on pure poetry. In terms of its tone, it hinted at a certain direction or, to put it another way, it frequently served, in varying degrees, as a corrective and a guide once I'd embarked on my second phase. Gradually in my writing, I tended towards the expression of personal sentiments. Although there are in the poetry of this period clear traces of the lyricism of [the Russian poet] Yesenin as well as folk songs, the most important thing was that, realizing the charm of ordinary reality, I allowed my poetry to return to everyday language and everyday things. If the feature of the poetry of this period was its song-like quality, the predominant feature in the poetry I wrote after the 1990s was a narrative intonation and the pursuit a certain dramatic effect, only the themes were more concentrated and defined and, as a result, there was an intensification of the individual intonation—if you could call it an individual style, that is. On the whole, an important feature of my writing over the past 20 years is, from the perspective of life experience, delight, a delight which is always permeated with a kind of innocence or the arrogance of the self-taught.

Zeng: Have you met with any particular problems or difficulties in your writing? If so, how did you deal with them?

Lü: In a way you could say that writing is all about dealing with problems and difficulties. In my own writing, what is most important to me is the conditions of writing. If the conditions are right, when you start to write, everything will sort itself out accordingly.

Zeng: What are your most important influences? What kinds of poetry—ancient or modern, Chinese or Western—do you like and what influences have they had on you?

Lü: As someone who was born in the 60s of the previous century, and who grew up in the family of an ordinary office worker, the literary education I received in my early years was extremely limited. As far as classical poetry is concerned, from a young age I only managed to learn—imperfectly—a few poems off by heart, but still these classical writings always seem to be able to exert a subtle, moulding influence on one's character, and even through the gaps in language of that time, they revealed a certain contents, a certain rhythm—this was the impression of my youth. I couldn't memorize many poems, but the rhythm stayed with me. I think this fragmentary impression has influenced my understanding of poetry all along, and continues to do so even now. Words, images, rhythms. In the mid-1970s, when I was forced to leave high-school and go and settle in the countryside, I came across a battered old copy of Pushkin's poetry my sister had somehow got a hold of on one of my visits back home. The translation was by Zha Liangzheng, and was, I guess, my first contact with "foreign poetry" and, although I was left with any rhythm, it seemed to spark my youthful desires and—for the first time in the course of my very limited reading of literature—like some kind of heretic, I shut myself away in an atmosphere of worship. I went about this in secret, and it brought about changes: namely, I could carry on my love of poetry using another kind of language and, what's more, the direct, vernacular language of these translations was, after all, a more suitable vehicle for me to convey what was on my mind to a certain female student. While we're on the subject, I should mention that once in an interview, I was asked what made me take up writing and I said that it was falling in love that started it. I mean the same thing here. What I really want to say is that this collection of Pushkin's poetry was a concrete revelation to me. After that, what I really must mention is my reading a year later of some early poems by Shu Ting published in a magazine put out by the cultural centre in my hometown. The shock I felt on reading her majestic, exquisite lines was the same I received from Pushkin. I should point out that I mention Shu Ting not because I had the good fortune a year after that to get to know her personally, worshipping her as many of her admirers did, but because Shu Ting (a woman's voice) gave me the presentiment that something was about to happen, perhaps the sense that we were on the threshold of a new era (back in those days I paid little attention to the proclamation that the Cultural Revolution was over). It was only after I got to know Shu Ting that my presentiments were proved to be correct. Thanks to her, I began to read the Today! magazine, and poets such as Bei Dao and Mang Ke. I should mention that the influence of their poetry on me at that period in time was critical—it began to give me an awareness of language. Yes indeed, they dragged poetry back into the midsts of life, like a fresh breath of wind. To this day I still can't understand why people at the time called their poetry 'obscure'. Through Shu Ting, I also got to know Jin Haishu and Hei Dachun, my first poetry friends of my own generation. Jin Haishu, with his air of a student of philosophy, enlightened me in many ways, while Hei Dachun, with his love of wine, was like a messenger from the Beijing poets Bei Dao and Mang Ke and, although our acquaintance was brief, his vagrant, rebellious lifestyle and his frequent, spontaneous recitals of beautiful lines of poetry really opened my eyes and, more importantly still, he brought home to me an intense form of lyricism. What's more, he brought me the first two foreign poets I really loved: Yesenin and Lorca. As a result, these two became unerasable voices in my soul for a long time period of time after that. Of course, there were also poets such as Li Bai and Pablo Neruda. Robert Frost, who influenced me deeply in the 1990s, was my own discovery. I could make no less that ten lists of poets whom I have liked at different times with different degrees of intensity; their differences from one another [reflects] the constant variations in the goals I pursue in my writing, but what's even more important, such pursuits [enable] you to return constantly to your starting point, to return to a place that is honest to yourself. For me, Yesenin, drags my inspiration back to the small town-life of my childhood, while Lorca makes me fall in love with folk songs, from which I get a vague feeling of poetry's origins in music. As for Frost, he guides me on how to speak calmly and naturally when faced with everyday things. Of course, all these influences are brought about by different life experiences, but as I see it nowadays, irrespective of language, feelings or taste, I always seems to be forever returning to some kind of starting point. In addition, I must also add the influence of modern painting. If I've had any insights into the forms of language, I'd say the greater part of these have derived from my understanding of modern painting.

Zeng: What is your view of elements of poetry such as language, technique, the imagination etc.? When you write poetry, which are the elements you pay most attention to?

Lü: Poetry is a particular means by which we return to language. Different periods, and the different conceptions individuals have of the craft of poetry, maintain different understandings and objectives, but from the outset they always imply the inter-relationship of various elements, as well as hinting at a certain orientation, a certain tone, as well as a self-trascendence. It is these things that enable a poem to go on astonishing people. But without the effect of the imagination, none of these elements can cause surprise. Sometimes, I even feel that the deployment of technique is a part of the imagination. Good poetry always makes these elements appear in the most appropriate way, so for this reason, all I can really say is that when I write, what concerns me first and foremost is whether I've manage to make all these elements complement one another. This is not only a matter of technical control, but also a question of experience that enables you to understand how to maintain a certain sense of the proper limits, to comply with the self-sufficient orientation of language, thereby obtaining a certain naturally integrated effect.

Zeng: Do you incline more to poetry's intellectual nature or its artistic nature? To put it another way, how to handle the relationship between these two things?

Lü: I incline to the view that the poem is primarily a thing and not the representation of thought. 'Thought' in this case is a form of workmanship exterior to poetry; when you are confronted with a theme, thought is already present in it, expressing a concern for certain values, but a successful work is the successful transformation [of this thinking], one that enables it to become imagistically clear in the language of the poem. In my case, dispelling thought so that it becomes a deep-seated attitude towards—and interest in—things, or a kind of intention that cannot be put into words but which constantly permeates the "between the lines", is something that I strive hard to reach in my writing.

Zeng: What kinds of abilities or qualities do you think the poet ought to possess? Briefly summarize your views on these.

Lü: The power of imagination—everything else comes after that. They are matters to do with culture or comprehension. That's all I have to say.

Zeng: Please talk about your relationship as a poet with everyday reality. What effects does your life experience have on your writing?

Lü: Broadly speaking, writing itself implies a special relationship with reality. We all live in an extremely complex reality, and we are all without exception ordinary people. The thing is though, when you choose to pursue artistic creativity, there seems to be a greater sense of distance with respect to reality, making people sense more or less that you have a different orientation, while you yourself can easily become fatalistic—you have had no choice but to make your response to all this already. It seems that certain people are destined to produce certain kinds of things. When we look back over the past, we often feel that we have lost certain things, but sometimes it is not necessary to regret these losses—they are the result of past experiences. In the works of my early period there are certain innocent, straightforward qualities, like the feelings you had the first time you fell in love, but now there are other things that seem to arouse your interest more. What I mean is: what we write inevitably changes along with our lives. These changes—directly or indirectly—manifest themselves in between the lines of what you write. To talk about my own experience for a moment, when I was a little over thirty, I went to New York, where I lived what was in fact a very closed off and rather lost life. You could say that this was me taking a sniff on my own at a lonely life experience, something totally different from previous circumstances. At times like that, there is less of an exaggerated unbosoming of oneself in the things one writes, and more of an osmosis. Something indistinct. At this time, there were changes in my style. Nowadays, I often do physical work where I live in the mountains and this helps me to understand the original meaning of artistic creativity. If originally poetry simply meant making things, then going off and doing something else is also interesting. Starting off with this in mind can gradually help me go beyond all those various ambitious expectations outside of poetry while at the same time making me careful at all points about language, a feeling of respect.

Zeng: Please discuss the current situation of contemporary Chinese poetry and its future prospects. Also, what plans or expectations do you have for your writing now?

Lü: Up to the present day, the development of contemporary Chinese poetry has unavoidably gone through its own movements, and this in my view is quite normal. Not a few individuals have written poetry that possesses a true style. These styles make manifest to us the fundamental conditions of the various periods of the contemporary age. Although I have always taken exception to the phrase "mood of the times", I continue to believe even now that the avant-garde thinking implicit in [this phrase] is the main cause of various phenomena in contemporary Chinese poetry. Regardless of what the motives are for the promotion in poetry circles of so called 'popular' writing and 'intellectual' writing, both of these writings are the result of a shared spirit of experimentation. It seems as if everyone dreams of creating an utterly unique text. But that miracle can only ever happen to individuals. Yu Jian's File 0 is an example of genius from the past few years. Its artistic power and enormous sense of reality gives one an impression that what Yu Jian has been through and what our age has been through are exactly the same thing. Then there is Han Dong's Jia-yi , a profound work that would seem to prove that his catch-phrase "poetry has its end in language" exerts its influence over a still younger generation.

By continuing to use our website, you agree to our privacy and cookie policy.

Sign up for our newsletter

Eclectic but curated. smart without snark. ideas journalism with a head and heart..

Sign up for the Zócalo newsletter to get our latest essays, poems and updates on our (always) free events.

A UNIT OF ASU MEDIA ENTERPRISE

Zócalo Public Square

Ideas Journalism With a Head and a Heart

Ode to the American Bus

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

How many of us grow rapturous in the presence of a bus? The number, I’d guess, is relatively small. Hulking metal loaves of the urban landscape, buses do not, when rattling past, draw voices down to a reverential hush. Heads don’t turn. Some buses are admittedly charming. Think of London’s double-deckers. Think of a school bus, first day of class. Others, though, are comically awkward, like the long bendy kind, their waistlines accordioned round corners. Only a few are truly memorable: Rosa Parks, Montgomery, Alabama, 1955; Ken Kesey, Merry Pranksters, the ’60s; Keanu Reeves, Los Angeles, Speed .

This collective disdain, born of class warfare and the American obsession with cars, does buses a disservice. They’re democratic institutions, sight-seeing stalwarts, and the delivery system for poetry—both found and made. To ride one among neighbors, the stamp of your municipality affixed to its hide, is to bind the communal and the commuter. Of course, buses break down. Of course, they’re late. But it’s the gap between their purpose and their product, their design and their delivery, that tells the story, in miniature, of the U.S.’s efforts to fulfill its obligations to us all.

I’ve missed countless buses. More than a handful have missed me. I know the taste of exhaust, the bite of the rain. And yet I still swoon over the routes and the timetables, the stops and the seats, of my bus-riding life. My swoon grew only more swoony after a pandemic and a move reduced my ridership to near nil. Since 2016, I’ve lived in rural Indiana. There are no buses. And so I am nostalgic for a time when cosmopolitanism and contagion-free air were commonplace.

What do I love about buses? Repetition comes to mind. Eavesdropping too. I love watching the glass shelters of bus stops sail by like diving bells. I love knowing, by the sound of a speed bump or the scrape of a pendulous branch, how near I am to home. This reminds me of verse, which—formal or free—thrives on patterns. And it reminds me of the poetry of my fellow passengers: “Nope, you’re good,” a woman reassures a man, “we could eat off your face.” (Was his beard mangy? His brow stained?) Later, a few seats over, a daughter shares a cookie with her dad: “Daddy, don’t eat the crumbs!” (He stops.)

Such found poetry flourishes just below a published kind: those colorful signs, linked up like train carriages, that line a bus’s interior. They usually advertise bail bondsmen or prohibit loud music. Their language is boilerplate or cant. At least it was until, 30 years ago this year, the Poetry Society of America and New York City collaborated on a series of poems that went—in a spatial sense only—right over our heads. They called it Poetry in Motion, and it recast the poem, that most highbrow of literary artifacts, as a public good.

That project spawned other projects in other cities. All offer a respite from the hectoring advertisement or the moralizing drone of the PSA. In the era before smart phones, the bus poem gave us a little entertainment. Now, it releases us from our screens.

What was the first Poem in Motion? Walt Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” It’s there that the poet declares, to riders of ferryboats past, present, and future, that he too “was one of a crowd.” It’s a democratic statement, and democracy, to my mind, is what makes poetry and buses so symbiotic. Metaphor is an equal sign, a union, a democracy of the world’s disparate parts. Poetry thrives on it, and short poems rely on it more. Here’s the most famous Anglophone poem about public transportation, as it first appeared in 1913, by Ezra Pound:

In a Station of the Metro The apparition of these faces in the crowd: Petals on a wet, black bough.

Metaphor makes dissimilar things seem suddenly, surprisingly alike. These ghostly faces, for instance, and “[p]etals on a wet, black bough.” In Pound’s poem, the colon unites these opposites . Among American democracy’s disparate elements, it’s the franchise, the social contract, and—I like to think—public transportation. Is it any wonder that the literary critic I.A. Richards named the second half of any metaphor, the imagined part (here, “petals”), the vehicle? It’s where the imagination goes.

In America, Whitman saw this link first. Plenty have seen it since. The rush hour crowd is a stand-in for the demos . The confines of the carriage are a metaphor for the country. Poems about public transportation are always already poems about ourselves. “[M]ingled / black and white / so near / no room for fear,” Langston Hughes writes in “Subway Rush Hour.” Where urban density meets urban diversity, Hughes argues, racial acceptance stands a chance.

That’s when my belief in ex omnibus unum—what I’ve come to call this rumbling urge, this latter-day hope, that public transit can rejuvenate public life—was born.

In “Flat American Waltz,” a double sonnet that replicates, in its elaborate, circuitous syntax, an urban bus route, Kevin González reminds us that bus riders enter an American experiment that’s still hurtling forward, herky-jerky and unsure. “Let’s all believe,” he writes, “in the place, / these hard plastic seats are taking us.”

That’s harder to do these days, what with the republic in peril, and I wonder if my nostalgia for buses isn’t just a nostalgia for better times. From 2008 to 2016, I lived in cities and rode buses all the time. Violent insurrections felt foreign and a skinny Black guy from Chicago was president, buoyed by a coalition—people of color, white liberals, urbanites—that looked a lot like my fellow bus riders.

That’s when my belief in ex omnibus unum— what I’ve come to call this rumbling urge, this latter-day hope, that public transit can rejuvenate public life—was born. But ours is an era of the MAGA caravan and the Google bus, the Uber infiltration and the airplane mask fight. Today I wonder if we can pull the stop cord on our current predicament, hop off, and walk home. The trouble, of course, is that we’re already there.

But I wallow. I detour. At such moments, when I get lost in the now, I remind myself that any good poem exists in the now and the after. I think of Allen Ginsberg’s “In the Baggage Room at Greyhound,” a poem in which the poet—depressed, working as a luggage clerk—“realized shuddering / these thoughts were not eternity.” Or I consider the school bus, which is, for so many, the first taste of shared transit. All across America, school buses are pressing a connection between jostling rides and dense reads into the hot pleather seats of kids’ minds.

Or I rewatch Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson , a movie that taught me how riding a bus is like reading a poem. Both take you, once you’re on board, wherever they go. And the poet, like the driver, played here deftly by Adam Driver, leads you around its turns. And Driver here is both a poet and a driver; he writes poems at lunch. And the word “verse” comes to us from the Latin versus , “a “turn of the plow.” Every stop is a stanza break. Every segment shows you a little more of your world.

That movie helps me to remember that I’ve lived a privileged life, a life where the bus is a study not a slog, while Michael Spence drove a Seattle bus for 30 years, then documented his experience in The Bus Driver’s Threnody. Or I’ll reread Terrance Hayes’s “Woofer (When I Consider the African-American).” It begins when the poet forgets his “father’s warning about meeting women / at bus stops” and ends, well… I’ll let you read the poem.

Poetry lifts us and persists past us. It time travels. It makes you miss your stop. And when the era seems hellbent on collision, and you’re forced to watch it, bracing for an impact that you cannot avert, poetry reminds you that others lived through worse. “I am with you,” Walt Whitman writes in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” “[j]ust as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt.” This from a guy who survived a Civil War. Who saw the limbs piled high.

But it’s not Whitman that I’d choose for a seatmate on a long bus ride. No, that’d be Elizabeth Bishop, whose shoulder I’d look over, sharing her prismatically sure vision of the world.

Take “The Moose,” the poem where she and a busload of passengers spot the eponymous beast in the middle of the road. The driver stops. No one moves. “Why, why do we feel / (we all feel) this sweet / sensation of joy?” she writes, as the moose loiters, majestically unaware. Because we’re in this together. Because we’ll soon be moving on.

We've recently sent you an authentication link. Please, check your inbox!

Sign in with a password below, or sign in using your email .

Get a code sent to your email to sign in, or sign in using a password .

Enter the code you received via email to sign in, or sign in using a password .

- Subscribe to our newsletters:

Sign in with your email

Lost your password?

Try a different email

Send another code

Sign in with a password

Privacy policy

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Poetry in motion allows the individual a platform to express themselves and be heard, whether it be through an impassioned speech, a powerful slam dunk, or a piece of literature that subtly yet realigns the way a reader looks at the world.

Poetry in Motion® places poetry in the transit systems of cities throughout the country exposing it to millions of viewers every day. It was launched by MTA New York City Transit and the Poetry Society of America in 1992.

Since its New York debut, Poetry in Motion has appeared in more than 25 other cities across the nation. A new anthology edited by Alice Quinn, The Best of Poetry in Motion, will include half of the 200-plus poems featured on subways and buses, as well as a history of the collaboration.

If the thing’s a moving body then we might call it “poetry in motion.” For example, we sometimes claim there’s a certain “poetry” to baseball. Or we describe one of its players as “poetry in motion.” But what exactly do we mean by “poetry” in these boasts?

The term “poetry in motion” is typically used to describe something graceful, effortless and beautiful. It can refer to a ballet performance, a piece of art or a piece of writing that has strong emotion, creativity, and a powerful impact.

Here is provided a discussion of how poetry is simply a body in motion effected by and following Newton’s Laws. When I spend an hour a day to ponder word placement and rhyme my pencil is run by a variety of forces. There is a push of my hand against the paper and forward as a line is drawn.

Abstract. Algernon Charles Swinburne was a nineteenth century English poet and critic who until the first decade of the twentieth century was the most well-known and critically appreciated of the...

Poetry in Motion places poetry in transit systems of cities throughout the country.

As far as I'm concerned, poetry means that form of writing most capable of providing a motion internal to language, but in the broadest sense of form, it is becoming more and more difficult for us to define what poetry is.

What was the first Poem in Motion? Walt Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” It’s there that the poet declares, to riders of ferryboats past, present, and future, that he too “was one of a crowd.” It’s a democratic statement, and democracy, to my mind, is what makes poetry and buses so symbiotic.