- ENCYCLOPEDIA

- IN THE CLASSROOM

Home » Articles » Topic » Issues » Issues Related to Speech, Press, Assembly, or Petition » Rights of Students

Rights of Students

Philip A. Dynia

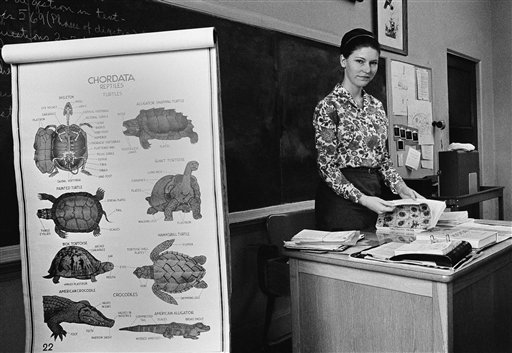

The first major Supreme Court decision protecting the First Amendment rights of children in a public elementary school was West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943). The Supreme Court overturned the state's law requiring all public school students to salute the flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance.In this photo, a 6th grade class in P.S. 116 in Manhattan salutes the flag in 1957. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Public school students enjoy First Amendment protection depending on the type of expression and their age. The Supreme Court clarified in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969) that public students do not “shed” their First Amendment rights “at the schoolhouse gate.”

Constitutional provisions safeguarding individual rights place limits on the government and its agents, but not on private institutions or individuals. Thus, to speak of the First Amendment rights of students is to speak of students in public elementary, secondary, and higher education institutions. Private schools are not government actors and thus there is no state action trigger.

Another important distinction that has emerged from Supreme Court decisions is the difference between students in public elementary and secondary schools and those in public colleges and universities. The latter group of students, presumably more mature, do not present the kind of disciplinary problems that educators encounter in grade school and high school, so the courts have deemed it reasonable to treat the two groups differently.

The court has protected K-12 students

The first major Supreme Court decision protecting the First Amendment rights of children in a public elementary school was West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943) . A group of Jehovah’s Witnesses challenged the state’s law requiring all public school students to salute the flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance . Students who did not participate faced expulsion.

The Jehovah’s Witnesses argued that saluting the flag was incompatible with their religious beliefs barring the worship of idols or graven images and thus constituted a violation of their free exercise of religion and freedom of speech rights. The Supreme Court agreed, 6-3. Its decision overturned an earlier case, Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940) , in which the court had rejected a challenge by Jehovah’s Witnesses to a similar Pennsylvania law.

In Barnette , the court relied primarily on the free-speech clause rather than the free-exercise clause. Justice Robert H. Jackson wrote the court’s opinion, widely considered one of the most eloquent expressions by any American jurist on the importance of freedom of speech in the U.S. system of government. Treating the flag salute as a form of speech, Jackson argued that the government cannot compel citizens to express belief without violating the First Amendment. “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation,” Jackson concluded, “it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”

In the early 1960s, the court in several cases — most notably Engel v. Vitale (1962) and Abington School District v. Schempp (1963) — overturned state laws mandating prayer or Bible reading in public schools. Later in that same decade, the Court in Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) found an Arkansas law banning the teaching of evolution in public schools to be an unconstitutional violation of the establishment clause .

In Tinker , resulting in the court’s most important student speech decision, authorities had banned students from wearing black armbands after learning that some of them planned to do so as a means of protesting the deaths caused by the Vietnam War . Other symbols, including the Iron Cross, were allowed. In a 7-2 vote, the court found a violation of the First Amendment speech rights of students and teachers because school officials had failed to show that the student expression caused a substantial disruption of school activities or invaded the rights of others.

In later cases — Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser (1986) and Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988) and Morse v. Frederick (2007) — the court rejected student claims by stressing the important role of public schools in inculcating values and promoting civic virtues. The court instead gave school officials considerable leeway to regulate with respect to curricular matters or where student expression takes place in a school-sponsored setting, such as a school newspaper ( Kuhlmeier ) or an assembly ( Fraser ). Years later, in Morse v. Frederick (2007) , the Court created another exception to Tinker , ruling that public school officials can prohibit student speech that officials reasonably believe promotes illegal drug use.

College students receive different levels of protection

The different level of speech protection for students in institutions of higher education, who are generally 18 years or older and thus legally adults, is evident from several cases. Students on college and university campuses enjoy more academic freedom than secondary school students.

In Healy v. James (1972) , the court found a First Amendment violation when a Connecticut public college refused to recognize a radical student group as an official student organization, commenting that “[t]he college classroom with its surrounding environs is peculiarly the ‘ marketplace of ideas .’”

In Papish v. Board of Curators of the University of Missouri (1973) , a graduate journalism student was expelled for distributing on campus an “underground” newspaper containing material that the university considered “indecent.” The court relied on Healy for its conclusion that “the mere dissemination of ideas — no matter how offensive to good taste — on a state university campus may not be shut off in the name alone of ‘conventions of decency.’ ”

However, in recent years, courts have applied principles and standards from K-12 cases to college and university students. For example, in Hosty v. Carter (7 th Cir. 2005) , the 7 th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that college officials did not violate the First Amendment and applied reasoning from the high school Hazelwood decision. More recent lower court decisions also have applied the Hazelwood standard in cases involving curricular disputes, professionalism concerns and even the online speech of college and university students.

Students in private universities — which are not subject to the requirements of the First Amendment — may rely on state laws to ensure certain basic freedoms. For example, many state cases have established that school policies, student handbooks and other relevant documents represent a contract between the college or university and the student. Schools that promise to respect and foster academic freedom, open expression and freedom of conscience on their campus must deliver the rights they promise.

Students and social media

More recently, courts have examined cases involving student speech on social media. In 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a school could not discipline a cheerleader who had posted on Snapchat a vulgar expression about not making the varsity squad. The court said in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. that the school’s regulatory interest was lessened in regulating the speech of students off-campus and on social media and that the cheerleader’s comment on Snapchat did not substantially disrupt school operations.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated by David L. Hudson Jr. and Deborah Fisher as recently as 2023. Philip A. Dynia is an Associate Professor in the Political Science Department of Loyola University New Orleans. He teaches constitutional law and judicial process as well as specialized courses on the Bill of Rights and the First Amendment.

Send Feedback on this article

How To Contribute

The Free Speech Center operates with your generosity! Please donate now!

- MAKING INQUIRY POSSIBLE

Inquiries Filed Under:

- 12th Grade Government

First Amendment

About the inquiry.

This inquiry leads students through an investigation of students’ rights and the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. By investigating the compelling question, students consider the ways in which their rights provide a unique perspective on learning about the First Amendment and the extent to which schools are “special areas,” in which various courts have made rulings that may be seen as limiting students’ First Amendment rights.

Compelling Question

Are Students Protected by the First Amendment?

Staging Question

Read a story from the Washington Post about students in Ohio who were expelled for posting rap videos to their social media pages; then assess the actions of the school and the students.

What is the difference between the Tinker Standard and Fraser Standard as they relate to students’ free speech?

Complete a T-chart on the differences between the Tinker Standard and Fraser Standard.

Source A: First Amendment, Bill of Rights<br /> Source B: Excerpt from a summary of "Tinker v. Des Moines School District" <br /> Source C: Excerpt from a summary of Bethel School District v. Fraser

Does the “no prior restraint” rule apply to students?

Explain in a paragraph the extent to which the Constitution’s no prior restraint rule applies to the Hazelwood and Layshock cases.

Source A: Definition of the term “prior restraint” <br /> Source B: A summary of "Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier"<br /> Source C: Excerpt from a summary of "Layshock v. Hermitage School District"

How does the Supreme Court determine the limits of students’ rights?

Write a concurring or a dissenting opinion on Morse v. Frederick.

Source A: A summary of Morse v. Frederick<br /> Source B: Excerpt from Justice Thomas’s concurring opinion in Morse v. Frederick

Can school officials exert control over students’ use of social media?

Develop a claim supported by evidence about school control over social media that answers the supporting question.

Source A: Excerpt from Judge Kravitz’s Memorandum of Decision in "Doninger v. Niehoff"<br /> Source B: Excerpt from Judge Garber’s decision in "Evans v. Bayer"<br /> Source C: Excerpt from Judge Simon’s decision in "T. V. v. Smith-Green Community School Corporation"<br /> Source D: Excerpt from Judge Wilson’s decision in "J. C. v. Beverly Hills United School District"

Summative Performance Task

Argument: Are students protected by the First Amendment? Construct an argument (e.g., detailed outline, poster, essay) that addresses the compelling question using specific claims and relevant evidence from historical and contemporary sources while acknowledging competing views.

Extension: Have an informed debate in class about whether students are protected by the First Amendment.

Taking Informed Action

Understand: Investigate the challenges to New York students’ First Amendment rights in the digital age by researching cases of cyberbullying and legislation aimed at protecting students.

Assess: Evaluate the school’s current cyberbullying and social media policies and the extent to which they align with recent First Amendment legislation.

Act: Evaluate the school’s current cyberbullying and social media policies and the extent to which they align with recent First Amendment legislation.

Your Voice Matters

Join c3 teachers.

C3Teachers.org facilitates open collaborative conversations among teachers as they tinker with their own instructional practice as it relates to the C3 Framework.

We'd Love to Talk

If you are interested in offering more professional development opportunities, rethinking or redesigning your social studies curriculum, we’d love to talk.

Copyright © 2024 C3 Teachers. All rights reserved.

Jun 17 Freedom of Speech for Students: Applications and Implications of the 1st Amendment on Campus

By: Ava Malkin Volume IX – Issue I – Fall 2023

I. Introduction and Background

In December of 1791, the United States government approved the first ten amendments to the Constitution, formally known as the U.S. Bill of Rights. [1] Colloquially referred to as the “freedom of speech,” the “freedom of religion,” “freedom of the press,” “the freedom of assembly,” and “the freedom of expression,” the First Amendment of the Constitution provides all American individuals with the liberty to practice their preferred religion, to verbally express their views, to write and publish these views, and to protest without interference from Congress. [2]

A multitude of Supreme Court cases have debated the extent to which this right may apply to extraneous circumstances, thereby outlining its unique inclusions and limitations. The unspoken extensions of the freedom of speech were specified rulings between 1943 and 1990. West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette (1943) found that there is no obligation to salute the flag if it violates an individual’s religious beliefs, thereby implying that the First Amendment also covers the right not to speak if an individual prefers to do so. [3] Cohen v. California (1971) ruled that offensive speech, which in this case involved cursing language in relation to the draft, is permitted to convey political messages as long as it is not directed at or threatening harm to particular individuals. [4] Buckley v. Valeo (1976) permitted the contribution of money to political campaigns, limiting the quantity based on “the size and intensity of the candidate's support,” further defining and narrowing the concept of political expression. [5] Virginia Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Consumer Council (1976) and Bates v. State Bar of Arizona (1977) clarified business entities’ ability to advertise legal services and the prices of prescription drugs. [6,7] Texas v. Johnson (1989) and United States v. Eichman (1990) maintain the right to engage in symbolic speech, such as the burning of a flag with the intention of protest. [8,9] Most importantly for the present subject, Tinker v. Des Moines (1969) found that students can wear armbands to protest a war since no members of a school community “shed” their rights upon entering educational facilities. [10]

There are also notable limitations to the First Amendment, which cases from 1957 to 2007 outline. Obscenity and the distribution of indecent materials remains unprotected by the freedom of expression, as Roth v. United States (1957) highlighted this unconstitutionality concerning both speech and press. [11] Additionally, although Tinker v. Des Moines (1969) and Cohen v. California (1971) allow for the use of accessories and certain offensive phrasing with the intention of protesting a war or conveying political perspectives, United States v. O’Brien (1968) clarified that the First Amendment does not authorize the destruction of draft cards via arson. [12] Free speech is also restricted in cases of incitement of lawless action, as delineated by Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), where constitutionality was upheld in relation to the charges against a Ku Klux Klan member for advocating for crime and terrorism. [13] For students in particular, Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988) established that schools can restrict student publications that are not in line with an educational function, Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986) prevents obscene or “lewd” speech at school-sponsored activities, and Morse v. Frederick (2007) prohibits the promotion of drug use at school-sponsored occurrences. [14,15,16]

For students in particular, it is of utmost importance to remain aware of these liberties, as it has become abundantly clear that nuances apply to the verbal, written, and active undertakings of participants on campuses. However, this amendment-provided right is not entirely applicable to students enrolled in all types of institutions, as those in private spaces retain different free speech protections due to their varying private funding. The First Amendment reserves the government’s right to uphold and place restrictions on the freedom of expression for all government-funded systems, but because private institutions do not receive funding from the government, they set their own standards for forms of communication engaged in on campus or via institutional means, for example, the school newspaper. Accordingly, private schools are not subject to free speech compliance to the extent required by public institutions, but many nonetheless enforce school-specific policies and statements that students adhere to. Therefore, the present focus relies upon proceedings in relation to students in public institutions given the universal applicability of the First Amendment for these individuals.

II. Relevant Precedents

Beginning with the two most relevant decisions, one would benefit most from delving into both Tinker v. Des Moines (1969) and Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988), as these two Supreme Court cases set the precedent for the admittances and restrictions on free speech for students.

i. Tinker v. Des Moines (1969)

On December 16th, 1965, John F. Tinker, Mary Beth Tinker, and Christopher Eckhardt, 15-year-old, 13-year-old, and 16-year-old junior high school students, respectively, in Des Moines, Iowa, wore black armbands in protest of the atrocities occurring due to the Vietnam War, outwardly expressing their desire for a truce. With the knowledge that the school recently inhibited the use of armbands as protest against the war and that the consequence of breaking this newly adopted policy would be suspension, the Tinker siblings and Eckhardt proceeded with the symbolic accessories and each received a suspension. The young protestors then took to court through their parents and filed a complaint in the District Court for the Southern District of Iowa against the school for their form of chastisement, pursuing nominal damages.

The district court upheld the constitutionality of the school administration’s decision to discipline this self-expression, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit affirmed; however, the Supreme Court reversed this decision. A 7-2 majority decision of the Warren court found that the policy of reprimanding an individual for declaring their views, even via physical articles of clothing, restricted the students’ freedom of speech. The majority of the justices, with the exception of Justice Hugo L. Black and Justice John M. Harlan II, held that the First Amendment shall extend onto school property. [17] Both the petitioner and the court recognized that these armbands were entirely separate from any potential disruption to the school environment, meaning the school could not justify their punishment and infringement upon a student's freedom of speech based on the argument that this conduct interferes with and disrupts the operation of the school. Tinker and Eckhardt’s bands in no way obstructed school events, but instead, their suspensions were a byproduct of fear of disturbance, thereby infringing upon their rights provided by the first article of the Bill of Rights.

Although some may argue the strong influence of parents in this case, the prominent outcome involves students retaining their First Amendment rights within school walls. The most valuable takeaway from this case indicates that students’ freedom of speech extends to physical means of expression, even applying to protest against specific aspects of war, and that these rights cannot be limited by the school administration unless there are significant impacts to the learning environment. Generally, the majority opinion epitomizes the importance of this case, where Justice Abe Fortas wrote, “It can hardly be argued, that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the school-house gate.” [18]

ii. Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988)

In May of 1983, Cathy Kuhlmeier and two other students of Hazelwood East High School, a public school in Saint Louis, Missouri, recognized that their two newspaper articles were withheld from publication in the school paper, entitled The Spectrum . The pieces, which described students’ personal experiences with pregnancy and parental divorce, were completed in participation with a Journalism II course as part of the high school’s curriculum, and the teacher submitted the pages to the school's facility, particularly principal Robert E. Reynolds, for approval. Reynolds withheld the articles from the May 13, 1983 printing because they were deemed inappropriate due to their references to sexual activity and birth control, their lack of security in the anonymity of students, and their lack of parental control over the narrative of their own conduct and personal relationships. [19]

Kuhlmeier and her two fellow former student writers took to the District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri in St. Louis, claiming the school violated their First Amendment rights. The district court ruled that the administration had the authority to remove the articles from the school-sponsored paper, and the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit reversed. The Supreme Court reversed this appellate decision, finding that the principal's prevention of publication was not unconstitutional. Public schools retain the right to control the narrative of their own publications, unlike public forums of journalism, which would follow processes similar to that of Tinker . [20] A 5-3 ruling of the Rehnquist Court confirmed that the Missouri public school acted in the interest of protecting student identities, parental information, and the overall integrity of The Spectrum .

The preeminent outcome of this case was the distinction between “the press” via public format, where the freedom of speech is consistently upheld, versus via school-funded publications, where the narrative is controlled by the school administration specifically. This means that schools reserve the right to edit or deny papers from being distributed for their specific content, especially if it does not align with the school’s values and/or it compromises the privacy or safety of its students and their families.

iii. Clarification of the Paradoxical Nature of Tinker and Kuhlmeier

Although these two cases seem somewhat paradoxical in nature, as one extends the freedom of expression via physical means and one limits the freedom of speech via written means, both cases still stand as the foundations for students’ freedom of speech, establishing rudimentary precedents for future free speech cases. Decided approximately twenty years apart, both cases tackle young students openly combating actions their schools have taken against them by citing their First Amendment rights. While their outcomes moderately oppose one another, the two decisions actually do not counteract each other because they simply relay different manifestations of the First Amendment: Tinker via anti-war armbands and Kuhlmeier via school-funded journalism. One does not overrule the other, and each retains its proper specifications on the freedom of expression within educational institutions. Therefore, scholars that argue conflicting outcomes to the extent that “ Kuhlmeier eviscerates the Supreme Court’s decision in Tinker ” are not entirely accurate, and neither marks “the end of an era” for all of a student's freedoms. [21] Instead, these two landmark cases simply provide guidelines for future cases and cultivate workings for future proceedings and acts that may continue to protect students and facilitate their intellectual growth via speech, writing, and protest.

III. Applications of these Precedents in the Supreme Court

i. Major Cases that Cite Tiker and Kuhlmeier

The Court has since applied these decisions in a variety of similar cases where students openly advocate for their First Amendment rights to be upheld within their academic environments. To fully comprehend the extent to which students’ rights can be both protected and limited by a school environment, one must delve into a few situations that cite Tinker and Kuhlmeier for support or evidence of previous acceptance of a specific inclusion or infringement.

In Healy v. James (1972), students part of an independent “local chapter” of Students for a Democratic Society at a state-funded college were denied acknowledgment as an official campus organization, as this recognition would permit the group to use campus facilities, bulletins, and newspaper space. [22] Dr. James, the school’s president, considered this group’s independence from the National Students for a Democratic Society insufficient for registration, as the organization as a whole tended to support violence and disruption as a means to argue for rights. The students took to the district court to claim a violation against their First Amendment rights, citing Tinker v. Des Moines (1969). The lower court deemed the president’s rejection of the group constitutional, as it maintained the intention of protecting the school community from potential violence; however, the Supreme Court held that James’ action violated the freedom of speech, finding that the district overestimated the burden of proof of potential harm and underestimated infringement upon the First Amendment.

This does not solely pertain to groups and organizations, as it may involve only one student and their actions. Papish v. Board of Curators (1973) involves a journalism student at the graduate school of the University of Missouri, Barbara Papish, being expelled for distributing a highly offensive newspaper on campus. This paper consisted of political cartoons where policemen sexually assaulted the Statue of Liberty and the Goddess of Justice alongside a description using swear words. [21] Papish then took to court, claiming that the university could not censor her freedom of expression using the guise of bylaws that prevent “indecent” speech. In consideration of both the Tinker and the Healy decision, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the young petitioner, finding that the school must reinstate her and restore her credits, as the paper she gave out could not officially be considered obscene, meaning the school could not reprimand her for their disapproval of its content. [23] Even though strictly “obscene” content is unprotected by the freedom of speech, the court did not classify the newspaper under this category, meaning Papish and her expression remained intact and the school could not punish her without significant proof of harm or concern for the school community.

One may now recognize that the First Amendment expands to individuals, groups, and written means, but this also is relevant in cases of religious expression. Widmar v. Vincent (1981) deals with officials at the University of Missouri at Kansas City preventing a “Cornerstone” religious group from accessing school buildings or property with the purpose of worship and teaching. The group sued the university in the Western District of Missouri, utilizing Tinker as confirmation that this religious discrimination infringed on their First Amendment right of free religious exercise and speech. While the lower court regarded the university’s prevention of specific religious expression as constitutional, the Supreme Court held that the school’s policies were both exclusionary and discriminatory by failing to permit equal access to all religious groups, thereby violating Cornerstone’s First Amendment rights. [24]

Such applications also began appearing in cases of speeches by one student to a crowd within the academic environment. In Bethel School District v. Frase r (1986), Matthew Fraser, a student at a public high school, received disciplinary reprimands for delivering a sexually promiscuous speech filled with metaphors and innuendos to an audience of 600 students despite receiving warnings from teachers and the assistant principal. Upon receiving a suspension and being removed from the list of potential graduation speakers, Fraser filed suit against the school by applying Tinker to argue that his First Amendment right was violated. This lower court found that the school’s consequences were unconstitutional; however, the Supreme Court reversed this holding, deciding that the suspension and reprimand were not a product of a political viewpoint, and because the speech breached the school’s mission and policies, the school retained the right to incite repercussions without disobeying the freedom of expression. [25] This serves as evidence that a school has grounds to prohibit the use of “lewd” or vulgar speech on its property.

This form of expression on school property is not limited to verbal statements, as it may also apply to clothing, posters, and banners. Morse v. Frederick (2007) deals with the latter, where Frederick and other students at their high school-supervised event held a banner with a phrase perceived by Morse, the school’s principal, to be promoting illegal drug use. Upon direction to remove the banner, Frederick refused, and the banner was seized, causing Frederick to receive a suspension for violating school policy by advocating for drug use. Frederick filed suit, employing Tinker as support for a violation of his First Amendment rights. The Supreme Court held that the school did not breach Frederick’s freedom of expression via the confiscation of his pro-drug banner and subsequent suspension, as Kuhlmeier serves as evidence that school officials can limit what is presented in school-sponsored environments. [26]

The argument based on First Amendment right infringement even experienced clarifications in more recent times, particularly in relation to technology use by students. B.L. v. Mahanoy Area School District (2021) considers Brandi Levy, a sophomore honors student at Mahanoy Area High School, who experienced an expulsion from her position on the cheering squad following her “Snap”, also formally entitled SnapChat, a social media publication featuring a picture of her holding up a middle finger with inappropriate language captioning the image. The school, coaches, and administrators justified by claiming the school reserves the ability to discipline a student for his or her disrespect to the school. Through her parents, B.L. filed a motion, citing Tinker as verification that schools are unable to restrict student speech, particularly off-campus, via broad and discriminatory policies. The Supreme Court found that, although schools may regulate (a) vulgar speech, (b) speech regarding drug use, and (c) speech that may negatively alter the impression of a school — particularly via the newspaper as seen in Kuhlmeier — schools may not control expression off-campus; this indicates that the school infringed upon B.L.’s rights by suspending her for her social media use. [27]

Tinker and Kuhlmeier are also often cited in cases that do not exceed the lower circuits, where situations like Hardwick v. Heyward (2013) make their way to the Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, using Tinker to claim their school violated their First Amendment rights by punishing them for wearing clothing with confederate flags and imagery. [28] The court, however, found that the school did not infringe upon any rights, claiming this is an instance of potential racial tension with its effects extending far beyond protest-related paraphernalia and into the fields of student discomfort and unease. This means Kuhlmeier becomes more applicable in that the school claims to have been acting in the best interests of its wider community as well as its safety, meaning there is no official violation of freedoms. This one example of a lower court case provides further evidence for the malleability and situational nature of these rights even though Tinker and Kuhlmeier delineated specific areas of limitation.

ii. Takeaways from these Cases

These cases all provide evidence for the circumstantial nature of the application of Tinker and Kuhlmeier , where students tend to be favored in their protection of free speech as long as their expression does not cause or threaten substantial harm to the wider school community. While Healy v. James (1972) and Widmar v. Vincent (1981) deal with student associations, both political and religious, and the rest of the aforementioned cases recognize individual students, the freedom of speech has identified itself as a factor that, under most circumstances, protects students’ actions and beliefs within their identified groups or along their own personal courses; these conditions are mostly limited by the Constitution when the group or individual causes tangible harm or disruption to the academic institution and community as a whole, as demonstrated by Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986), Morse v. Frederick (2007), and Hardwick v. Heyward (2013). From the original rulings to those that ensued, Tinker and Kuhlmeier outline the eligibility to utilize the argument of First Amendment right infringement for students.

IV. Relevance to Students Now: Knowing One’s Rights

i. Current State and Importance for Students

To summarize the overall implications of the aforementioned decisions, students are permitted to exercise their First Amendment right on campus and via school-funded means as long as it does not present a threat to campus integrity or school member safety, contain lewd language, or reference illicit drugs. This right can thereby be exercised through a variety of means, whether it be through physical representations—such as clothing and appropriate banners—symbolic actions, or even intellectual representations that employ the newspaper and social media platforms.

Some scholars and individuals express concern for the larger implications of Kuhlmeier in that it provides a framework to limit students’ freedom of expression; however, in terms of written means specifically, efforts are being made to ensure that this case is not the universal standard for unjustified censorship of student perspectives. For example, the Student Journalism Free Speech Act, which is active in seventeen states, ensures educational institutions may not prevent publications unless “such speech is libelous, an invasion of privacy, or incites students to commit an unlawful act, violate school policies, or to materially and substantially disrupt the orderly operation of the school.” [29] This thereby confirms the necessity for considerable inappropriateness or concern for its wider audience in order to violate a student’s First Amendment right on campus. Additionally, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) expresses that they continuously fight for the “free expression of all ideas, popular or unpopular” ever since their 1920 founding, and they work in courts and within communities to defend and preserve this right for students. [30] Beyond new policies themselves, some organizations have provided suggestions for campus speech codes, including the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) which compiled exemplary policies from various higher-level institutions to assist all in understanding what safe, fair, and legal policies are. FIRE, by citing various university policies, outlines the possibility of maintaining the freedom of speech, while also preserving academic freedom and promoting equitable and secure campuses. [31]

This extends far beyond student writing into general learning experiences and intellectual growth, with restrictions on teachings and readings that call for further action regarding the First Amendment. Dean Erwin Chemerinsky of the University of California, Berkey, School of Law surmises the query of if the First Amendment principles extend into “laws that prohibit the teaching of critical race theory.” [32] To exemplify this concern, Chemerinsky mentioned Tennese’s Prohibited Concepts in Instruction, which prevents teaching topics that might cause an individual to “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish or another form of psychological distress solely because of the individual’s race or sex” or that implies an “individual’s race or sex” would make them “privileged, racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.” [33] He also recognized Florida’s Stope WOKE Act [34], which prevents teachings usually involved in diversity training, questioning how these types of proceedings will affect both teachers’ and students’ ability to converse, communicate, and learn within public school environments. Using Chemerinsky’s mindset, the concept that student’s free speech also extends to classroom content also calls for concern about book bans; PEN America, an organization dedicated to preserving free expression through literature, finds that book bans dramatically increased recently, with around 1,500 new bans in this recent 2022-2023 school year alone. [35] While some may argue that withholding certain topics from classrooms and literature is not a direct infringement upon student’s freedom of expression, such bans, proceedings, and censorships prevent students from truly learning and forming their own views; this implies that such proceedings can be considered an infringement upon First Amendment rights, which brings up Chemerinsky’s questions about how courts will choose to deal with this. In current circumstances, where restrictions and bans are so prevalent, students, teachers, and even parents should be aware of the preceding in their state or district to ensure they may maintain a well-rounded comprehension of not simply their personal rights, but also of generally diverse academic and social content.

As previously mentioned, in relation to college campuses specifically, public institutions are intended to follow the policies of the government, while private institutions make their own policies surrounding their students’ freedom of expression. Cornell University takes a particularly intriguing stance on this First Amendment right, particularly by combining private and public funding among its various colleges. In other words, they are required to follow the constitutional guidelines in the state-assisted colleges and can make their own guidelines in their privately-supported colleges. Cornell University recognizes First Amendment policies in their Faculty Handbook by acknowledging that “[f]reedoms to engage in research and scholarship, to teach and to learn, to express oneself and to be heard, and to assemble and to protest peacefully and lawfully” provide vital foundations for the institution and its students; these liberties are also granted via their Statement of Core Values, which states that Cornell University “value[s] free and open inquiry and expression—tenets that underlie academic freedom—even of ideas some may consider wrong or offensive.” [36] This indicates that the university’s policies essentially mimic that of the First Amendment, providing students with the ability to express their values and views within an academic context. Similar to the freedom of expression, these rights are only limited by the university in instances of abuse, which includes illegal acts as well as “discrimination, harassment, and sexual and related misconduct.” Cornell University openly recognizes that its students and faculty should respect the rights of others to facilitate a productive and safe academic, social, and working environment. [36] This environment can be consistently upheld if all members of the educational institution comprehend these guidelines and protocols in the expression of their First Amendment rights.

ii. Personal Perspective

While both Tinker and Hazelwood prevail as foundational proceedings for students’ First Amendment rights, it becomes easy to side with one over the other for their somewhat opposing outcomes, despite dealing with slightly different free expression manifestations. I find it more logical to follow the preceding of Tinker over Hazelwood . Tinker recognizes the ability to maintain freedom of expression via items of clothing and, via its later citings, freedom of speech and religion, as long as a student does not threaten or cause any damage or distraction within the school environment. Hazelwood does not appear to follow this guideline, censoring student work due to its content potentially causing harm or discomfort within the student body and parents. Principle Reynolds never permitted the publishing of these papers, so I theorize that Hazelwood ’s First Amendment right actually could have been infringed upon. Without viewing the effects of the papers, the school had no distinct evidence of supposed severe disruption or detriment, meaning they based their argument off of worry and assumptions. These inferences, although upheld in the Supreme Court, potentially caused more harm than good to the school community. The argument that topics of pregnancy and divorce could be inappropriate for the student body is valid, but other students might benefit from reading about such topics to learn and potentially even identify with others who experienced similar struggles. Additionally, Hazelwood East High School not only took a strong stance that Kuhlmeier ’s writing, even as part of a class, was not acceptable to be published, but their actions also signaled to all other students that their hard work and writing might never merit a page in The Spectrum . This is in no way an attempt to argue that educational institutions should not have a say in what is discussed within their publications or their environment in general; later cases, such as Papish v. Board of Curators (1973), demonstrated that journalism should not be limited within a school environment due to their content. However, it is entirely contradictory to allow students to wear armbands, identify as part of a group, or outwardly express their views via social media, but not to permit the discussion of relatable and realistic topics within a school setting.

iii. A Call to Action

Using the current judicial standings on students’ freedom of speech and what can be done to protect this right, both technological and intellectual should be considered in relation to the First Amendment. Because B.L. v. Mahanoy Area School District (2021) recognized that social media posts made off-campus and outside of school hours are protected under the freedom of speech and cannot be punished within the school environment, there are potential additions to the First Amendment, or at least more timely concepts that can be applied, in relation to forms of media beyond Hazelwood’s written expression, including onto more technologically-contemporary forms of expression, particularly social media. While social media is implied by the general and applicable First Amendment, it is important for a stance by either the federal government or individual state governments, on whether B.L. v. Mahanoy Area School District (2021) forms a precedent for all student social media posts, and extends that ruling to encompass other social media applications used outside of school. Additionally, due to contemporary educational restrictions, seen in the prevention of critical race theory and book banning, it is time that the federal government makes statements and enacts policies to protect against such restricting censorship policies; current variance among states and districts not only creates ambiguity, while also limiting widespread knowledge and the formation and expression of one’s own beliefs and values. There are improvements and explanations necessary to fully comprehend the First Amendment for students, but as of right now, Tinker and Hazelwood provide the most specific guidelines for acceptable expression.

[1] 1 U.S. Const. amend. I-X.

[2] U.S. Const. amend. I

[3] W. Va. State Bd. of Educ. v. Barnette , 319 U.S. 624, 63 S. Ct. 1178 (1943)

[4] Cohen v. California , 403 U.S. 15, 91 S. Ct. 1780 (1971)

[5] Buckley v. Valeo , 424 U.S. 1, 96 S. Ct. 612 (1976)

[6] Va. State Bd. of Pharmacy v. Va. Citizens Consumer Council , 425 U.S. 748, 96 S. Ct. 1817 (1976)

[7] Bates v. State Bar of Ariz. , 433 U.S. 350, 97 S. Ct. 2691 (1977)

[8] Texas v. Johnson , 491 U.S. 397, 109 S. Ct. 2533 (1989)

[9] United States v. Eichman , 496 U.S. 310, 110 S. Ct. 2404 (1990)

[10] Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cmty. Sch. Dist. , 393 U.S. 503, 89 S. Ct. 733 (1969)

[11] Roth v. United States , 354 U.S. 476, 77 S. Ct. 1304 (1957)

[12] United States v. O'Brien , 391 U.S. 367, 88 S. Ct. 1673 (1968)

[13] Brandenburg v. Ohio , 395 U.S. 444, 89 S. Ct. 1827 (1969)

[14] Hazelwood Sch. Dist. v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260, 108 S. Ct. 562 (1988)

[15] Bethel Sch. Dist. v. Fraser , 478 U.S. 675, 106 S. Ct. 3159 (1986)

[16] Morse v. Frederick , 551 U.S. 393, 127 S. Ct. 2618 (2007)

[17] Oyez. “Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District.” Oyez Supreme Court Cases. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1968/21.

[18] Kelly Shackelford, "Mary Beth and John Tinker and Tinker v. Des Moines: Opening the Schoolhouse Gates to First Amendment Freedom," Journal of Supreme Court History 39, no. 3 (November 2014): 372-385

[19] Oyez. “Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier.” Oyez Supreme Court Cases. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1987/86-836.

[20] United States Courts. “Facts and Case Summary - Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier.” United States Courts. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.uscourts.gov/educational-resources/educational-activities/facts-and-case-summary-hazelwood-v-kuhlmeier.

[21] Abrams, J. Marc, and S. Mark Goodman. "End of an Era-the Decline of Student Press Rights in the Wake of Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier." Duke LJ (1988): 706.

[22] Healy v. James , 408 U.S. 169, 92 S. Ct. 2338 (1972)

[23] Papish v. Bd. of Curators of Univ. of Mo ., 410 U.S. 667, 93 S. Ct. 1197 (1973)

[24] Widmar v. Vincent , 454 U.S. 263, 102 S. Ct. 269 (1981)

[25] Bethel Sch. Dist. v. Fraser , 478 U.S. 675, 106 S. Ct. 3159 (1986)

[26] Morse v. Frederick , 551 U.S. 393, 127 S. Ct. 2618 (2007)

[27] Mahanoy Area Sch. Dist. v. B.L ., 141 S. Ct. 2038 (2021)

[28] Hardwick v. Heyward , 711 F.3d 426 (4th Cir. 2013)

[29] Student Journalism Free Protection Act, 2023

[30] American Civil Liberties Union. “Speech on Campus.” American Civil Liberties Union. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.aclu.org/documents/speech-campus.

[31] Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. “Model Speech Policies for College Campuses.” The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.thefire.org/research-learn/model-speech-policies-college-campuses.

[32] Chemerinsky, Erwin. “Education, the First Amendment, and the Constitution .” University of Cincinnati Law Review , 2, 92, no. 1 (2023).

[33] TENN. CODE ANN. § 49-6-1019 (2023).

[34] H.R. 7, 2022 Leg., Reg. Sess. (Fla. 2022) (Second Engrossed)

[35] PEN America. “Banned in the USA: State Laws Supercharge Book Suppression in Schools.” PEN America, August 21, 2023. https://pen.org/report/banned-in-the-usa-state-laws-supercharge-book-suppression-in-schools/.

[36] Cornell University. “Cornell Policy Statement on Academic Freedom and Freedom of Speech and Expression.” Office of the Dean of Faculty, n.d. https://theuniversityfaculty.cornell.edu/the-new-faculty-handbook/statement-on-academic-freedom-and-freedom-ofspeech-and-expression/.

Jun 17 The Catch-22 of Prop 22: Examining California's Classification of Gig Economy Workers

Jun 17 artificial intelligence transparency versus at-will employment: striking a balance in employment laws.

Essay On First Amendment In Schools

In Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment applied to public schools and that administrators had to provide constitutionally valid reasons for any specific regulation of speech in the classroom. However, in the 1986 case Bethel v. Fraser, it was ruled that educators were not violating students’ First Amendment right by censoring the content of their speech or writing. So are we, as students, protected by the First Amendment or not? Should we be able to write about a controversial topic as freely as any adult? I believe we should. The First Amendment applies to everyone, and under the First Amendment, we have freedom of speech , freedom of the press, freedom of religion, the right to assemble peacefully and petition the government. Freedom, by definition, means the right to do as you please without restriction. Freedom of speech “within reason” is no longer freedom of speech. …show more content…

It restricts not only how we write something, but also what we can write about. Students are discouraged from exploring and debating important topics simply because an issue may be deemed “too controversial.” This limitation applies to what a student chooses to write about in an essay, draw in a picture, or even display on a T-shirt. There should not be constraints on how students can creatively express themselves. Creativity in itself is the free form of ideas. What’s even more disappointing than this prejudice is that most young people aren’t aware of the restrictions they live under. Censorship sets unclear boundaries about what is okay and what is inappropriate. We all know the basics: we aren’t allowed to use profanities, and create images or essays that touch on drug use, violence, gangs or sex - however lightly. But did you know that you can be suspended for what your teacher or principal considers unnecessary expression of your religion or sexual

Argumentative Essay On The First Amendment

The first amendment grants religious freedom to all citizens of the United States but when does that religions power and actions go too far, and when are we supposed to draw the line? The First Amendment grants religious freedom to the Citizens of the United States allowing them to believe what they want and freely practice their religion. This goes as far to say what happens when their power goes too far. Whether it be deemed illegal or something that the states don't feel should be going on. Should we turn our cheeks and let it go on. I feel that there should be a point in which we do put limitations on people's actions in their religions. The Founding Fathers knew that freedom of religion was very important and one of the reasons they came to America. Therefore, we have the free exercise clause and the establishment clause. These all give citizens the right to hold their beliefs and practice their religions freely but, when those actions start to go against the law and harm other people then there is a point where we need to put limitations on them.

Summary: Pickering V. Board Of Education

The following cases are utilized: Pickering v. Board of Education, Mt. Healthy City School District v. Doyle, Connick v. Myers, Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeir, and Garcetti v. Ceballos. The case, Pickering v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court acknowledged teachers have the right to voice personal views as they relate to issues of public concern (Cambron-McCabe, McCathy & Eckes, 2014). More specifically, “The Pickering case is one of the most influential court cases concerned with the balancing of teacher’s First Amendment right to freedom of expression against the state’s interest in promoting efficient schools” (DeMitchell & DeMitchell, 1990, p 385). If a teachers voices personal views that are damaging to coworkers, school procedures, ones’ occupational performance, and does not directly relate to public concerns there will be grounds for disciplinary actions (Cambron-McCabe, McCathy & Eckes, 2014). This constitutional rights stands both inside and outside of the classroom, as educators can utilize various methods of communication, such as social media, written artifacts, visual relics, and expressive language. In the case, Hazelwood v Kuhlmeier, a teacher’s personal opinion can be expressed within the contours of a classroom when applicable to pedagogical reasons. More specifically, “Reasoning that the teachers was speaking for the school, the court concluded that teachers are not entitled to express views in the classroom that are counter to the adopted curriculum” (Cambron-McCabe, McCathy & Eckes, 2014, p. 242). If the topic discussed within the classroom is controversial in nature it must be censored, thus deeming appropriate to a youthful audience. In conclusion, it is imperative for educators to ‘think before they speak,’ as their actions can have detrimental impacts on key stakeholders as well as their

The First Amendment in High School Essay

What is the age that a person should be able to claim rights under the first amendment? The first thing would come to most people's mind is eighteen. However, upon examination, someone could easily justify that a sixteen year old who is in his or her second year of college would have the ability to form an opinion and should be allowed to express it. What makes this student different from another student who, at sixteen, drops out of school and gets a job, or a student who decides to wear a shirt that says "PRO-CHOICE" on it? While these students differ in many aspects such as education level, their opinion can equally be silenced under the first amendment. One of the most blatant abuses of the first amendment right to free speech is

Freedom Of Prayer In New York Public Schools

In the first amendment, it is stated that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the exercise thereof.”. From this, it made clear that the founding fathers’ original intent was for the Government to take a neutral position with respect to religion; the Government was not to favor any one religion over another. “Almighty God we acknowledge our independence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parent, our teachers and our Country. Amen.” In 1951, that prayer was conducted in class every morning in all New York public schools as ordered by New York State Board of Regents; it was called a “nondenominational prayer”. The short prayer was created with the intent of developing students’ moral

Informative Essay: The First Amendment Of The Constitution

Given the nature of the constitution, and the incredible relevance and reliance on which we place upon the sacred document, the rights it adheres to us are the most important of US legislature. The very first amendment of this constitution. It pertains to our freedoms concerning speech, expression and religion. While the order of amendments perhaps are arbitrary, some may find that they are not; would freedom to communicate freely not be important? Would freedom of creation and artistry not be important? What about freedom pertaining to religion? Would it be arbitrary? Of course not! The first amendment is, and forever shall be, a testament to our freedoms; it is the key to our liberties, and the key to progress.

Essay on The First Amendment

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is part of our countries Bill of Rights. The first amendment is perhaps the most important part of the U.S. Constitution because the amendment guarantees citizens freedom of religion, speech, writing and publishing, peaceful assembly, and the freedom to raise grievances with the Government. In addition, amendment requires that there be a separation maintained between church and state.

The First Amendment Essay

The 1st Amendment forbids Congress from enacting laws that would regulate speech or press before publication or punish after publication. At various times many states passed laws in contradiction to the freedoms guaranteed in the 1st Amendment. However broadcast has always been considered a special exemption to free speech laws for two reasons. 1) the most important reasons is the scarcity of spectrum and the 2) is the persuasiveness of the medium. Because radio and TV come into the house, and may be heard or seen by unsupervised children, the government feels a special responsibility to protect the American people. As Herbert Hoover said to, "doublegaurd them."

- 4 Works Cited

The First Amendment is the first section of the Bill of Rights and is often considered the most important part of the U.S Constitution because it guarantees the citizens of United States the essential personal freedoms of religion, speech, press, peaceful assembly and the freedom to petition the Government. Thanks to the rights granted by the First Amendment, Americans are able to live in a country where they can freely express themselves, speak their mind, pray without interference, protest in peace and where their opinions are taken into consideration, which is something not many other nationalities have the fortune of saying. The Founding Fathers were the framers of the Constitution of the U.S., and the responsible for the

Persuasive Essay On The First Amendment

The First Amendment one that is watered down, serves as example of the freedom we as Americans have. It is best known as the amendment that lets us say what we want when we want. There is more to it that gets overlooked. It blocks government from establishing a theocracy, grants the people the right to peacefully assemble and protest the government for a redress of grievances. Our press is independent and is given freedom to publish at will. Our freedoms embolden us to speak out and organize for progress and against society's wrongs. Sometimes groups will organize to speak out but will sink to extreme measures as a means of expression. The first amendment has seen challenges in recent months. “Donald Trump referred to the press, and I'm quoting his exact words, as "dishonest, disgusting, and scum."Just ten days ago, you might have heard in a press conference, President Donald Trump said that the "press is out of control."(Chemerinsky, 553). To clashes between different ideologies on college campuses with some initiating riots. The first amendment grants many freedoms, however it does not grant protection from consequence.

Essay about The Second Amendment

- 22 Works Cited

“A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a Free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” - Second Amendment. Throughout history, this sentence of twenty seven words has caused an intense debate. The polemic is that some people claim that a gun control policy is unconstitutional, while others disagree and even say it is necessary in order to reduce crime. Now, what does gun control mean? If it means to analyze who is responsible enough to own a gun by a “Universal Background Check”; that sounds right to everyone. But in the article “What Are Obama’s Gun Control Proposals? An Easy Guide” published in the National Journal by Matt Vasilogambros. The author states that the “gun-control

Essay On First Amendment

The First Amendments is a blessing that the United States is fortunate enough to have. First and foremost, First Amendment protects the right to freedom of religion and expression, without any government interference ("First Amendment" n.p.). The freedom of expression includes the right to free speech, press, assembly, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances ("First Amendment" n.p.). Redress of grievances guarantees people the right to ask the government to provide relief for a wrong through courts or other governmental action ("First Amendment" n.p.). People are allowed to practice their own religions and do not have to conform to one religion, all because of the First Amendment. People's rights are protected with no government interference.

The first and inargueably the most significant of the amendments to our Constitution is the First Amendment. The amendment that established our freedoms as citizens of our new confederation. The First Amendment insured, among other things, freedom of speech and of the press. Since the establishment of these rights, they have often been in question. People have debated over, "What is too much freedom?", and "When is this

The Importance of the First Amendment Essays

"Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of Religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech," this Amendment is the most important part of the constitution. Without free speech, we the people of the United States would not be able to speak openly and freely about issues that affect our everyday life.

Pros And Cons Of Censorship On Society

Censorship might keep our youth population innocent at first but it does not allow a complete knowledge to be learned. Sometimes hiding things from them can leave them curious to find out. Most likely they end up finding certain information and not understanding it completely. Likewise, they later make a claim or statement that isn’t supported and could end up getting them in trouble. Students always end up not knowing as much and allows them to make unreasonable claims. They don’t always end up getting a full understanding of things and end up jumping to conclusions because of this. “The American Library Association opposes censorship and urges you to do so, too” (Censorship in Schools).

Censorship in Schools Essay

- 15 Works Cited

Censorship cases often bring about debates over students’ first amendment rights. Students’ first amendment rights are important to preserve so that students can not be excluded from meaningful works or literature. It is understandable for the government to design educational plans as a way to get its voice into classrooms, but “the truth-promoting function of the First Amendment provides no reason, however, to question the right of students to explore a variety of ideas and perspectives, and to form and express ideas of their own” (Brown, 1994, p. 30). Schools already place a restriction on religious material or material addressing current political controversy (Brown, 1994).

Related Topics

- First Amendment to the United States Constitution

- Supreme Court of the United States

- Freedom of speech

- United States Constitution

Student First Amendment Rights

The First Amendment protects students and student journalists from censorship and retaliation in public schools and universities. As the Supreme Court has explained, students do not “shed their constitutional right to freedom of speech at the schoolhouse gate.” Read more about our work on behalf of students and student journalists here.

- Client Advocacy

- Amicus Briefs

- Training & Presentations

- News & Media

Fall 2024 Clinic Presentations

During the Fall 2024 semester, the First Amendment Clinic presented trainings on election safety for journalists, student press freedoms, Georgia’s sunshine laws, and First Amendment auditors’ right to record.

Clinic article cited in op-ed calling for “New Voices” law

Student journalists in Georgia are advocating for state-level protections of their First Amendment freedoms.

Spring 2024 First Amendment trainings & presentations

Throughout Spring 2024, the University of Georgia’s First Amendment Clinic provided trainings and presentations on a wide range of First Amendment issues to audiences including student journalists, educators, public officials, law enforcement, and members of the judiciary.

Clinic provides training on speech rights and media law to audiences around the state

During the Fall 2023 semester, the University of Georgia School of Law’s First Amendment Clinic trained students, journalists, local officials, law enforcement, and engaged citizens on a variety of speech and media law topics.

High school conduct agreements: Do they conflict with students’ speech rights?

Almost every public and private high school has a code of conduct they require students to follow.

Clinic goes on the road to conduct 1A trainings

The University of Georgia School of Law’s First Amendment Clinic conducted a record number of trainings during the Spring 2022 semester.

New Voices Georgia – Protecting high school press freedoms

Norins, C; Harmon-Walker, T. and Tharani, N., Restoring Student Press Freedoms: Why Every State Needs a “New Voices” Law, 32 GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY CIVIL RIGHTS LAW JOURNAL 63 (2021).

Prior review & prior restraint in school-sponsored media

Prior restraint is a type of censorship where speech or expression is stopped before it occurs.

Norins comments on students’ free speech rights post-Mahanoy

The following guest column by Clinic director Clare R. Norins was published in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution on June 28, 2021.

First Amendment rights on campus

The First Amendment Clinic, partnering with UGA’s Office of Legal Affairs, hosted a class on June 19, 2020 for UGA faculty and staff focusing on campus free speech issues.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Aug 11, 2023 · The court has protected K-12 students. The first major Supreme Court decision protecting the First Amendment rights of children in a public elementary school was West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943).

Oct 9, 2023 · It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker.” (Douglas) Evidence of such a phenomenon is shown in a survey conducted by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, stating that forty-two percent of students are aware that the First Amendment protects hate speech, yet another forty-eight percent of students ...

The First Amendment and Students On and Off Campus 1/9 THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND STUDENTS ON AND OFF CAMPUS: Rights, Responsibilities, and Repercussions Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech,

Construct an argument (e.g., detailed outline, poster, essay) that addresses the compelling question using specific claims and relevant evidence from historical and contemporary sources while acknowledging competing views. Extension: Have an informed debate in class about whether students are protected by the First Amendment.

Jun 17, 2024 · Cornell University recognizes First Amendment policies in their Faculty Handbook by acknowledging that “[f]reedoms to engage in research and scholarship, to teach and to learn, to express oneself and to be heard, and to assemble and to protest peacefully and lawfully” provide vital foundations for the institution and its students; these ...

It is understandable for the government to design educational plans as a way to get its voice into classrooms, but “the truth-promoting function of the First Amendment provides no reason, however, to question the right of students to explore a variety of ideas and perspectives, and to form and express ideas of their own” (Brown, 1994, p. 30).

Oct 20, 2023 · First, I want to look at the First Amendment and the content of education. Second, I want to examine the First Amendment and student speech. And finally, I want to talk about the First Amendment and the ability to determine and control the environment within an educational institution. Two caveats are important at the outset.

Aug 9, 2024 · The First Amendment protects students and student journalists from censorship and retaliation in public schools and universities. As the Supreme Court has explained, students do not “shed their constitutional right to freedom of speech at the schoolhouse gate.” Read more about our work on behalf of students and student journalists here.

administration. Research indicates that students are printing a very limited number of stories with any type of controversial content. All this would suggest a system of gatekeeping and an authority exercising censorship of student newspaper content, a direct violation of the First Amendment rights of high school students.

Protection of Students' First Amendment Rights - An Argumentative Essay Introduction. The First Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees important rights and freedoms to all citizens, including students within educational institutions. One of the most crucial rights protected by the First Amendment is the freedom of speech.